A madman who burned a wonder of the world for immortality (8 photos)

On the night of July 21, 356 BC, two great events occurred in the Mediterranean basin. One forever changed the course of history; the other forever wiped one of its greatest monuments from the face of the earth.

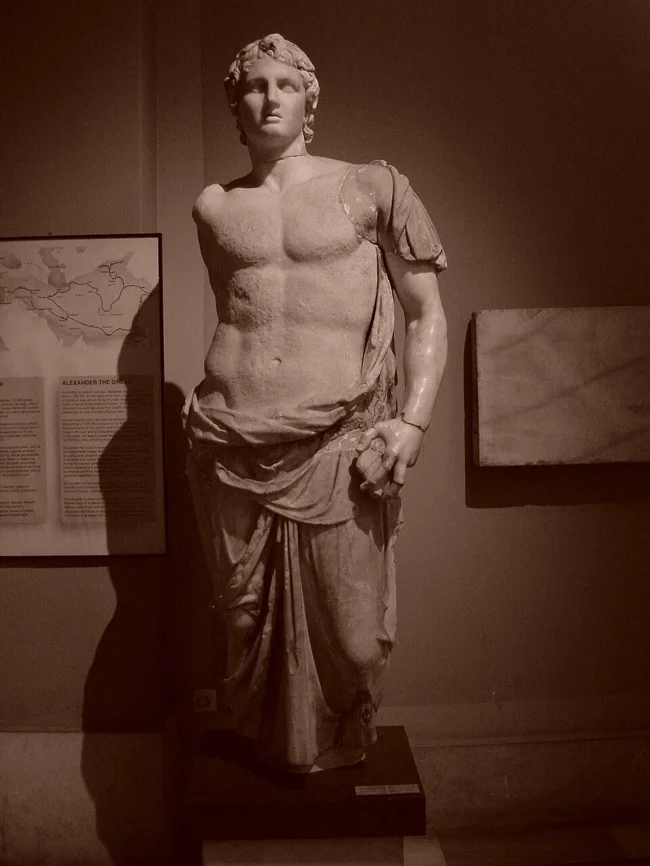

That very night, in Pella, the capital of ancient Macedonia, the wife of King Philip II gave birth to a boy. Years later, this child would create one of the greatest empires of the ancient world, forever rewriting the history of Europe, Asia, and northeast Africa. His name was Alexander the Great.

Posthumous portrait, circa 1683–1733

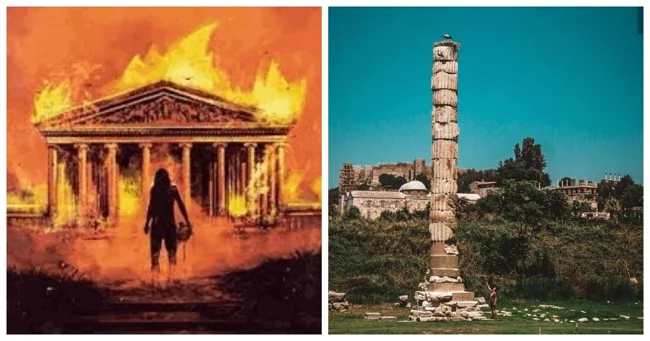

The second event was far more prosaic. An arsonist set fire to the temple. However, this was no ordinary temple. It was the greatest temple ever built. For two thousand years, travelers and scholars unanimously recognized it as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

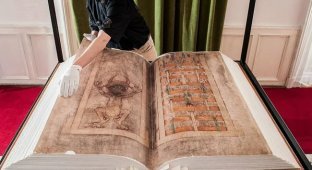

The Temple of Artemis was located near the ancient city of Ephesus, in modern-day Turkey. Dedicated to the goddess Artemis, it is believed to have been the first Greek temple built of marble. The grand structure stretched over a hundred meters in length and was half that width. Its outer columns rose twelve meters high, forming a double row and creating a spacious ceremonial gallery around the cela—the sanctuary where the cult statue of the goddess was kept. These columns were decorated with elaborate bas-reliefs.

Modern model of the Temple of Artemis in Miniatürk, Istanbul, Turkey.

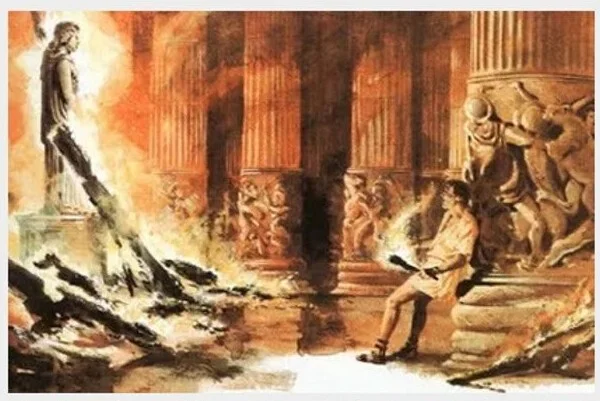

On the very night when the Macedonian kingdom rejoiced over the birth of a new prince, five hundred kilometers across the Aegean Sea, an insignificant man named Herostratus set out to write his name into history. He entered the Temple of Artemis and set it on fire. The wooden decoration of the temple, especially its beams, the statue of Artemis, and all the temple furnishings instantly burst into flames, and by morning all that remained of the wonder of the world were thirty-six blackened marble columns and smoking ruins.

Herostratus was immediately seized, and on the rack, the madman confessed to burning the temple in a futile attempt to immortalize his name. The Ephesian authorities not only executed the arsonist but also forbade anyone from mentioning his name, thereby condemning him to eternal oblivion—the very fate Herostratus feared most.

Alexander the Great

Many historians, such as Cicero and Plutarch, continued to honor this decree by omitting the name of the vandal, but some early writers violated this prohibition. The first to do so was Theopompus, who mentioned Herostratus in his biography of King Philip II, the Philippics. The earliest surviving source where this name appears is the Geography of the Greek historian and geographer Strabo.

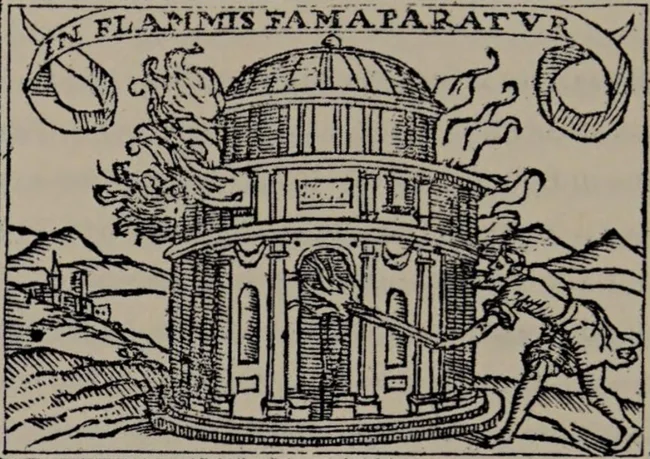

Herostratus burning the Temple of Artemis, painting by Sebastian de Covarrubias; the flag bears the Latin motto meaning "Glory consumed in fire."

The first-century Roman historian Valerius Maximus again mentions Herostratus by name. In his essay "On the Thirst for Glory," he cites Herostratus's act as an example of the vicious desire for fame through crime. He writes that the wisdom of the Ephesians wisely suppressed the memory of the villain, but "the eloquent genius of Theopompus" reinscribed him into history.

Indeed, Herostratus' name continued to surface in historical works for centuries. The 17th-century English author Thomas Browne wryly noted that the arsonist's fame outlived not only the names of his judges, but even the memory of those who tried to consign his name to oblivion.

Temple of Artemis, Ephesus, Turkey

After Herostratus' sacrilegious act, the citizens of Ephesus erected a new, even more magnificent temple on the site of the destroyed one. Fundraising took a long time. Alexander himself once offered to pay for the restoration, on the condition that his name be included in the dedicatory inscription. However, the Ephesians tactfully refused, declaring that "it is not fitting for one god to build temples in honor of other gods."

The new temple was colossal: 137 meters long, 69 meters wide, and 18 meters high, with more than 127 columns. It stood for six hundred years until it was destroyed by the East Germanic Goths in the third century. The stones of the collapsed temple were used to build other buildings. Some columns in Hagia Sophia, as well as several statues and decorative elements in Constantinople, originally belonged to the Temple of Artemis.