When did people realize that the Earth was a sphere? (7 photos)

In preparation for this article, I asked a hundred random people a seemingly simple question: "Who proved the Earth is round?" Most confidently answered: Columbus or Magellan. Some, especially those under thirty, recalled school stories about the daring explorer Christopher Columbus, who supposedly defied his ignorant contemporaries and the entire Dark Ages by sailing beyond the horizon and proving that the Earth is not a flat disk.

Image of our shared Home, taken by NASA's Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), which was launched on February 11, 2015, to observe the Sun and Earth.

Of course, there were also those who declared that "nobody knows what it's really like" because "the firmament," "space doesn't exist," and generally "we're not told the whole truth because we're small."

After all these responses, I was finally convinced that I had chosen the right topic.

I present to you a fascinating story about how ancient thinkers, two thousand years before Columbus, discovered that the Earth is spherical. Moreover, they were even able to calculate its size with an accuracy astonishing for their time. And all this without telescopes or satellites!

This is a story of the triumph of human genius.

Where did the legend of the "flat Middle Ages" come from?

The idea that people believed the Earth to be flat before the great geographical discoveries arose not in the Middle Ages, but much later. The main popularizer of this myth was the "father of American literature," Washington Irving. In 1828, he published a mythologized biography of Columbus, in which he vividly described how ignorant contemporaries, egged on by priests, ridiculed the idea of a spherical Earth, while the brave navigator heroically resisted them.

It's no coincidence that Irving's work, entitled "The History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus," is mythologized. What we have here is not a profound historical study, but a work of fiction. He invented a dramatic conflict for which there is no evidence. In fact, educated 15th-century Europeans had no doubt that they lived on a globe. And the intellectual elite debated with Columbus about the size of this sphere and the feasibility of the expedition.

The ancient Greeks knew everything two thousand years before Columbus.

The history of understanding the shape of the Earth goes back to ancient times. The first thinkers truly imagined the planet as flat. For example, Thales of Miletus in the sixth century BC believed that the Earth was a flat disk floating in an endless ocean. Anaximander even imagined it as a cylinder*, with people living at the top.

*Why a cylinder? I believe it has to do with the unification of two ideas: the flat world of humans and the vast, unexplored, and multi-leveled underground kingdom of Hades.

But already Pythagoras, who lived approximately 570–490 BC, proposed that the Earth was spherical. This idea was based on the ancient Greeks' belief that the sphere was a perfect geometric figure—worthy of such an important cosmic body as Earth (anthropocentrism has always been rampant). Remarkably, this was more of a philosophical concept than a scientific conclusion. Nevertheless, Pythagoras was proven right.

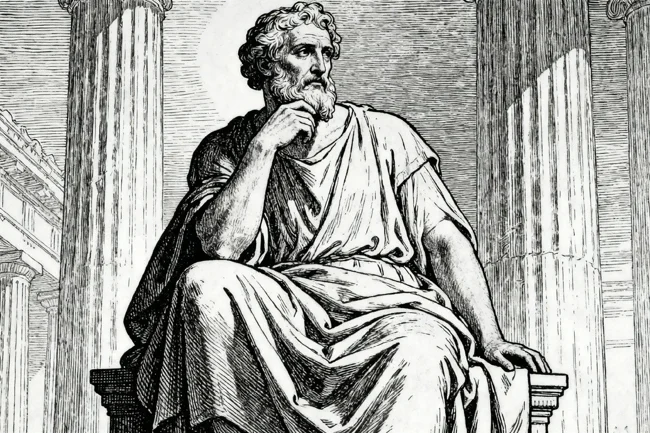

Aristotle made a real breakthrough in the fourth century BC. He didn't simply discuss the Earth's sphericity—he was the first to provide convincing evidence that remains relevant today.

The first argument concerned lunar eclipses. Aristotle observed that the Earth's shadow falling on the Moon always has an arc, regardless of the angle at which the eclipse occurs. The only body capable of casting such a shadow, regardless of the position of the light source, is a sphere.

The philosopher obtained his second proof by observing ships. When a vessel sets out to sea, the hull disappears above the horizon first, then the sails, and only then does the masthead disappear. If the Earth were flat, the ship would simply become smaller and smaller.

The third argument, which Aristotle presents in his treatise "On the Heavens" (c. 350 BC), is related to the stars. If you travel north or south, you can see how some constellations gradually disappear below the horizon, while others, conversely, appear. Those that rise high overhead in Egypt are barely visible near the horizon in northern countries. Such a difference is only possible if the Earth's surface is curved.

The Man Who Measured the Planet with a Stick

One of the main characters in this story is Eratosthenes of Cyrene, an ancient Greek scholar who, in 240 BC, not only confirmed Aristotle's conclusions about the Earth's sphericity but also measured its circumference. He did this with astonishing accuracy, using only logic, a knowledge of geometry, and... an ordinary stick.

Eratosthenes was the curator of the famous Library of Alexandria and had access to knowledge from across the ancient world. From an ancient scroll, he learned a curious fact: in the city of Syene (today's Aswan), at midday on the summer solstice, the sun occupies a position exactly at its zenith. At this point, shadows from objects become negligible, and the sun's rays penetrate directly to the bottom of deep wells. This phenomenon, described by an unknown author, inspired Eratosthenes to measure the size of the Earth.

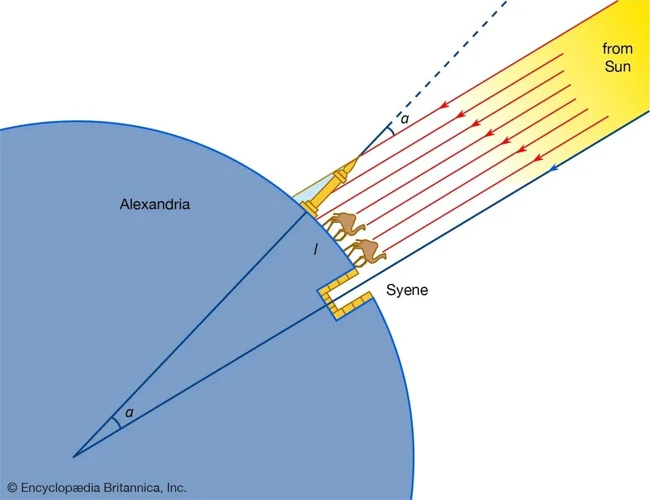

That same day, the scientist conducted an experiment in Alexandria. He drove a vertical pole into the ground and noticed that at midday it cast a short shadow. By measuring the length of this shadow and knowing the pole's height, Eratosthenes calculated the angle of incidence of the sun's rays—just over seven degrees, which corresponds to approximately one-fiftieth of a full circle.

Next, simple geometry came into play. In Syene, at midday on the solstice, the sun was directly overhead and cast no shadow, while in Alexandria, at the same moment, the pole cast a short shadow. The difference in the inclination of the sun's rays between the two cities was approximately seven degrees—that is, one-fiftieth of a full circle. This means that the distance between Alexandria and Syene corresponds to one-fiftieth of the Earth's meridian.

According to one version, Eratosthenes commissioned someone to measure this route, walking it and counting his steps. Another version says he used caravan trade data. The result was approximately 5,000 stadia.

Multiplying 5,000 by 50, the scientist obtained 250,000 stadia—approximately 40,000 kilometers. Today, we know that the circumference of the Earth's equatorial belt is 40,075 kilometers. This means that the error in Eratosthenes' calculations was less than one percent. And all this happened 2,197 years before the launch of the first artificial satellite.

What the Middle Ages Really Knew

Contrary to popular myth, medieval scholars did not lose the knowledge they inherited from their ancient colleagues and did not begin to believe the Earth was flat. This myth emerged during the Renaissance, when those in power tried at all costs to counter the "Dark Ages" with "enlightened science" (and in the 19th century, Irving exaggerated this myth, as noted above). In fact, educated people in medieval Europe and the Islamic world knew perfectly well that the Earth was spherical.

Furthermore, as early as the 2nd century BC, the Greek scholar Crates of Mallus created the first globe in history. Medieval cartographers, building on the achievements of their predecessor, also created spherical models of the Earth. That is, without accepting the planet's spherical shape, this would be completely meaningless.

It's important to note that the Church not only didn't persecute scientists for the idea of a spherical Earth, but also accepted it as fact. For example, Saint Ambrose of Milan—a bishop, preacher, and one of the Fathers of the Western Church—openly discussed the "globe of the Earth" as early as the 4th century. And Muslim astronomers of the time developed spherical trigonometry to calculate directions and distances to Mecca—calculations that only make sense on a spherical planet.

Columbus's Role in This Story

Christopher Columbus didn't prove that the Earth was round. This had long been known to everyone who had any connection with his expedition. The debate was about something else—the planet's size.

Columbus believed the Earth was 25-30% smaller than it actually is. He relied on the data of the ancient Greek philosopher and geographer Posidonius (135–51 BC), who, rejecting the more accurate calculations of Eratosthenes, underestimated the Earth's circumference. According to Columbus's calculations, the journey to Asia via the western route should have taken only a few weeks. He was opposed not by ignoramuses, but by the best geographers in Europe, who rightly pointed out that the ocean was too vast and such a voyage could end in disaster.

Ironically, it was Columbus's mistake that made his voyage possible. Had he known the true size of the Earth and the actual distance to Asia, he probably would not have decided on such a risky expedition—there simply wouldn't have been enough water and food supplies for such a journey. His fleet was saved by the existence of a then-unknown** continent—America stood between Europe and Asia, preventing the ships from being lost in the vast ocean.

**To be fair, it's worth noting that the Vikings likely reached the shores of North America five centuries before Columbus, but they didn't bother to document their discoveries, so their achievement was soon forgotten.

A 21st Century Paradox

And here's where history takes an unexpected turn. In our time, when thousands of satellite images of Earth exist, the International Space Station has been flying continuously for 25 years, and hundreds of people have been in space, millions of our contemporaries have begun to believe in a flat Earth.

According to sociological surveys, approximately 2-3% of the population in developed countries is convinced that the planet is disk-shaped. This is no joke. Entire communities, conferences, and internet channels exist dedicated to "debunking" the spherical Earth.

The age trend is particularly alarming. Among older people, over ninety percent believe the Earth is spherical. Among young people, this figure is significantly lower. The internet, which was supposed to be a tool for disseminating knowledge, has turned into a breeding ground for ignorance.

The ancient Greeks, without satellites or telescopes, were able to understand the shape of the planet and measure its size using a stick and a shadow. In the fourth century BC, Aristotle provided evidence that anyone can verify—just observe ships or a lunar eclipse.

And some of our contemporaries, with free and instant access to all human knowledge, manage to deny the obvious. This isn't an "alternative point of view" or "healthy skepticism." This is intellectual degradation—a regression back thousands of years.