The battle for garbage in the First World War (9 photos)

The war of 1914-1918 posed to the warring powers not only the issue of uninterrupted supply of multi-million armies with everything they needed, but also the proper disposal and recycling of the garbage that these armies left behind - from shell cups and fuel tanks to torn shoes and food scraps.

Both ordinary soldiers and specially created units designed to clear the battlefields of accumulating waste were engaged in this.

In addition, in parallel with this, methods for the secondary use of military property in the rear and in the army were being developed.

British experience

In the conditions of trench warfare and the organized supply of ammunition, such mounds of spent cartridges at artillery positions grew very quickly.

One British journalist astutely noted in 1918 that "nothing in the world is more senseless than an army. After training in peacetime economics, quartermaster sergeants who supervised warehouses with the maximum level of bureaucracy, on the battlefield force the army to fall into the most wild extravagance."

At the beginning of the war, "everything was sacrificed to the speed of attack. The first phase of the battle in the West ended with the opposing forces impotent in December 1914; ammunition on both sides was almost exhausted, and the ground on which they fought was full of the things they needed."

Apparently, the British army was one of the first to start collecting waste, because even before the economy was put on a war footing, it was in dire need of supplies. Thus, British sappers "showed great interest in empty jam, beef and sardine tins." The troops were in dire need of hand grenades, and engineers had to improvise on the basis of empty tins.

Contemporaries also note the initiative of two wounded British officers who were ready for further active service, but got the idea from the command to simultaneously help the troops on the ground and find work for refugee women by opening a clothing repair shop in France. They began by gathering a few seamstresses and repairing the most torn uniforms, gradually turning their institution into a magnificent organization for saving uniforms.

More important than clothing were shoes. The strength of the army depended on it, and for this reason, in June 1915, the British Commander-in-Chief John French appointed Major General Sir John Stevens as the head of the central shoe repair shops. One such was opened in Calais in the autumn of 1915, another was created in Mudros on the island of Lemnos during the Gallipoli operations and was subsequently taken to Salonika.

After the end of the fighting, such garbage had to be cleaned up.

Later, a workshop was opened in Alexandria for the army operating in Palestine, while the army in Mesopotamia repaired its boots in Basra. Instead of 250,000 new boots per week, only 100,000 were now required, which made it possible to save significantly on leather, and also to transfer part of the capacity of shoe factories to supply the allied troops (of course, not for free). At the same time, work was underway to create new models of shoes, with stronger soles and linings.

Since both defense and attack depended on artillery, the serviceability of the gun fleet was the key to victory. Sending each damaged gun to England was too expensive, so special repair shops were created, and then an entire repair plant, where skilled workers were brought from Britain.

Then, vehicle breakdowns forced a rethink of the concept of car repair shops, since even if the chassis was completely destroyed, the engine was often still in working order and could be used.

However, when the new British forces arrived in France in the summer of 1916, along with an incredible amount of materials, the old system of saving property and collecting scrap was abandoned. The amount of waste increased very quickly, since the quality of equipment delivered to the front was low due to poor raw materials, inexperience of new ammunition manufacturers, etc.

German Initiative

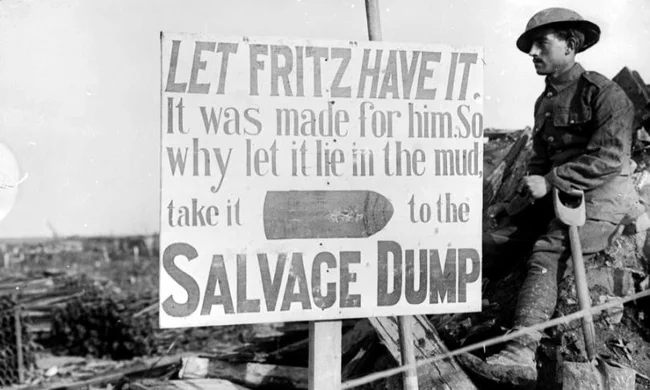

A sign at a British frontline dump calling for recycling not to be thrown into the mud, but to be collected for further processing and sent to "Fritz".

The Germans, under the influence of the Entente blockade and the sharp reduction in imports of vital materials, launched a gigantic campaign in the summer of 1916 to collect and recycle all resources available at the front and in the occupied territories: metal, fabrics, food waste, and sources of fat.

Products and waste of lead, tin, copper, aluminum, and other valuable metals were collected by special teams that went door to door in Belgium. Contemporaries noted that millions of empty tin cans were carefully collected and sent to metallurgical plants to extract valuable tin. Old cans were collected for this purpose even in neutral countries such as Switzerland and the Netherlands, and then sent to Germany.

All clothing supplies were also controlled by the German government. All worn-out woolen items had to be handed over to the authorities. Mattresses with wool or cotton stuffing were counted, confiscated and returned to their owners already stuffed with paper, seaweed or wood shavings. All leather stocks were accounted for by the army, and engineers and technologists conducted continuous experiments on the development of artificial leather and rubber for shoes.

Loading bones from which the fat will be extracted and then burned into bone charcoal. Empty kerosene cans are collected in the background.

All the supplies that the Germans managed to capture were carefully counted and sent to army warehouses. In this regard, as observers note, Ludendorff, Hindenburg and Mackensen were perhaps the best German "rescuers of things". After each enemy retreat, a quick and accurate recount of the captured property took place.

Interestingly, the most intensive campaign was aimed at collecting fats for the production of nitroglycerin. "At home, the Germans organized a systematic collection of fruit pits from which oil could be extracted, and began that strange search for fat that the Allies stopped laughing at when they also discovered that fat was one of the main problems of the war." In addition, fat was used to produce weapons lubricants. The campaign to collect fat gave rise to a lot of strange rumors, both among the Germans and their enemies.

Battlefield Scavenging

British soldiers burn tin solder out of empty tin cans.

The British also wanted to get their soldiers interested in scavenging and recycling. They began collecting battlefield rubbish towards the end of the Battle of the Somme in 1916, but officers were generally expected to supervise the men if they wanted their division to stand out in the eyes of the quartermaster general.

There were, however, enthusiasts like the Guards Brigade, which began collecting the property left in no man's land during the Third Battle of Ypres. The Guards collected, among other things, a million cartridges that had fallen out of cartridge pouches, and calculated that by collecting the waste from one battle they had reimbursed the salaries of their unit, including allowances for wives and children. However, it was impossible to save everything, and the weapons continued to lie in the ground after the battles for decades, posing a danger to civilians.

And in the autumn of 1917, Andrew Weir, the new British Surveyor General of Supplies, visited France in connection with the creation of a unit to collect salvage. As observers noted, a lot of work had already been done to collect fat, metal and rags, but Weir believed that this was not enough.

A British army depot for sorting and repairing soldiers' boots.

A feature of Weir's plan for preserving the economic strength of the Entente was a system of careful waste collection, set up at the very places where supplies were most quickly and recklessly consumed. Therefore, on Weir's instructions, a special post-battle collection department was created to coordinate military operations with commercial waste disposal work. Special efforts were made to prevent large stockpiles of salvage, as they were found to lead only to greater losses through spoilage.

Weir's initiative, although supported by the command, was sabotaged locally. The soldiers were already tired of endless battles and therefore looked for the slightest excuse to shirk the seemingly pointless (the extensive propaganda campaign was ignored) work of recycling waste and damaged property. In addition, the teams specially created for this were too few. The best help was provided by competitions between units with prizes organized in the winter of 1917 - spring of 1918. The winners were also given additional leave, for which the soldiers were ready to do anything. They began to happily go on patrols to the neutral zone, since this promised many finds suitable for recycling.

German "stahlhelms" carefully collected by the British awaiting disposal.

By the end of the war, when the American Expeditionary Force with its disposal and repair system arrived in Europe, the Entente and its opponents already had excellently functioning workshops and teams that found, dismantled, stored and repaired everything that could be useful in the future. Tin cans, cartridges, canisters, torn clothes and worn-out shoes always found someone who was ready to pick them up and hand them over for recycling for a reward.

French women select shell casings from scrap metal for recycling.