The heirs of the "Mechanical Turk": How AI startups have learned to deceive, not create (6 photos)

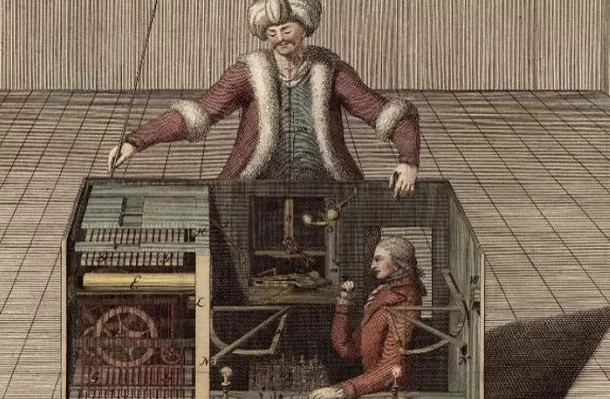

In 18th-century Vienna, Hungarian engineer Wolfgang von Kempelen astonished the court with a bizarre device: a large mechanical box that seemed capable of playing and even winning chess games without any human intervention.

The "Mechanical Turk," as Kempelen's invention was dubbed, became the talk of high society for decades and won victories over famous opponents, including Napoleon Bonaparte.

In reality, Mr. Kempelen created a seemingly complex mechanism with enough dummy wires and gears to deceive any suspicious observer. All this was necessary only to hide the real chess master inside, who would operate the machine.

Although Kempelen's secret was finally solved in the 1850s, the legacy of the "Mechanical Turk" lives on. Only now, instead of chess cabinets, we have the Natasha neural network, which is actually maintained by workers in India, and AI chatbots for programming, powered by employees in Kenya. Then there was the scandalous story of Amazon's Just Walk Out supermarket, where there are no checkouts or cashiers: shoppers simply add the necessary products to their cart and leave. Artificial intelligence then uses cameras to read the purchase amount, which is automatically debited from their card. The stores were closed when it was discovered that the AI was actually hundreds of idiots who were watching surveillance video for pennies.

These controversial startups have now been joined by Fireflies, a startup creating AI note-taking tools.

Sema Udotong, the startup's co-founder, recently admitted that at first, two people played the role of the AI.

"The best way to test your business idea is to become the product yourself. We told clients there was an AI that would join meetings." "In reality, it was just me and my co-founder calling into the meeting, sitting silently, and taking notes by hand," Udotong wrote on social media.

When a client needed meeting notes, the CTO explained, he or his startup colleague, Krish Ramineni, would sign in as "Fred," acting like a Siri. "We'd sit silently, take detailed notes, and send them ten minutes later," Udotong said. Moreover, the user agreement specified human participation, but no one read it.

This summer, the creators of Fireflies boasted that their brainchild is worth $1 billion, and 75% of Fortune 500 companies use the service to transcribe corporate meetings. These top companies pay $100 per month for Fireflies' AI assistant. Udotong claims the entire process is now automated, but social media commentators are skeptical, believing that Indians are behind the AI again.

Let's assume he's not lying, and the intelligence is indeed artificial, not real, but his admission highlights that successful startups value those who can sell more than those who are truly trying to change the world. Regardless of whether the work is done by a human or an algorithm, the startup market is more interested in the appearance of progress than in progress itself. This creates financial conditions that justify the initial deception, while also lining the founders' pockets.