5 of the Titanic's most vile passengers, whose names will forever remain infamous (7 photos)

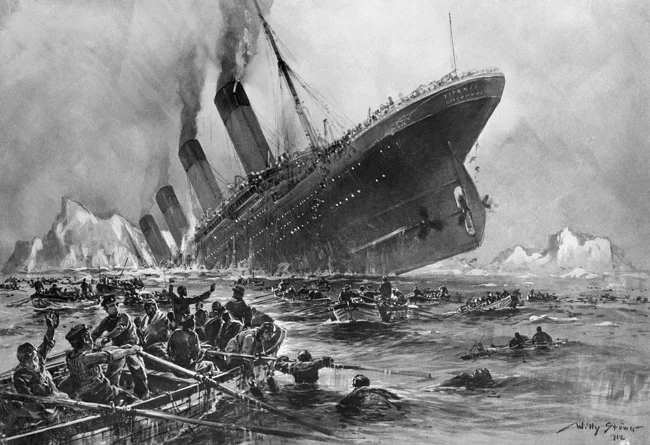

The sinking of the Titanic in April 1912 became the greatest test of human conscience, masculinity, and gentlemanly heroism.

That night, as the icy waters of the Atlantic pulled the sinking liner under them, hundreds of respected men—businessmen, doctors, officers, aristocrats—remained on deck until the very end, demonstrating true nobility. They gave up their places in lifeboats to women and children, said goodbye to their families, and set an example of manliness and calm.

Many of them died as honorably as they lived.

But against this backdrop of heroism, those who thought only of themselves stand out in stark relief. Those who broke the rules, hid, lied, bribed, or simply fled, pushing others aside for their own salvation. Their names evoke no respect, only condemnation. They have become symbols of cowardice and moral decline, dark shadows against the light of human valor.

In this article, we will tell you about the five most condemned passengers and crew members of the Titanic, whose actions will forever be shrouded in shame.

1. William Ernest Carter – the man who abandoned his wife and child on a ship for his own safety

William Ernest Carter was a wealthy American businessman and member of Philadelphia high society. He was traveling on the Titanic with his wife, Lucille, and their 11-year-old son.

When the liner began to sink and an evacuation was announced, Lucille recalls, her husband merely told the family to "get dressed and come on deck," then disappeared into the crowd – and she didn't see him again until the rescue ship arrived.

The sailors escorted Lucille and the child to the women's lifeboat No. 4. Carter himself found himself in Collapsible C, one of the last boats, which carried mostly men, including Bruce Ismay. This lifeboat departed almost empty, despite the fact that there were still women on deck.

When the family was reunited aboard the Carpathia, Carter casually began talking to his wife about breakfast. As if the tragedy of the last hours had nothing to do with him. Lucille later filed for divorce, claiming that her husband had abandoned her and their child on the sinking liner, saving only himself.

Carter's story became one of the most discussed examples of male cowardice on the Titanic, especially compared to the many gentlemen who voluntarily remained aboard, ceding the rescue to other people's women and children.

2. Bruce Ismay – the man dubbed the Titanic's "chief coward"

The head of the White Star Line, the owner of the Titanic, became the most hated man of the disaster. As one of the most powerful men on the ship, Ismay boarded a lifeboat, defying the "women and children first" rule.

The public pounced on him with accusations: he had used his authority, jumped on a boat, and condemned passengers to death by demanding it depart when half the seats were still available.

Furthermore, the press repeatedly reported that Ismay pressured the Titanic's captain to increase the ship's speed for a spectacular arrival in New York. It was later revealed that he demanded a private cabin on the Carpathia, shouted at the staff, and was in a state of severe nervous shock under the influence of opium.

Despite his lack of legal guilt, society's moral judgment was final: Bruce Ismay became a symbol of cowardice.

3. Daniel Buckley – The Man Who Disguised Himself as a Woman

The story of Daniel Buckley became one of the most high-profile scandals associated with the Titanic. When the lifeboats began to board, he and a group of men jumped into one. Officers immediately demanded that all men abandon the boat to make room for women and children.

Buckley panicked, burst into tears, and clung to the lifeboat. Then one of the women, taking pity on him, threw her shawl over his head, hiding his face. Because of this, he was mistaken for a woman and allowed to stay.

The other men who had jumped with him were pulled back onto the deck. In some cases, officers even used weapons to stop them from trying to take their places in the lifeboats. Buckley, however, remained unnoticed—and survived.

This act made him one of the most discussed and criticized figures, becoming a symbol of selfishness and cowardice on the Titanic.

4. Robert Hichens—the helmsman who refused to rescue drowning people

One of the crew members in charge of lifeboat No. 6, Robert Hichens, went down in history as the man who categorically refused to return to the nearly sunken Titanic, where hundreds of people were still fighting for their lives.

Passengers on his boat begged to be sent back to save those trapped in the icy waters. But Hichens insisted that after the Titanic sank, a huge whirlpool would suck everyone into the icy abyss, and the ship's boiler explosions would turn the deck into a debris field. Meanwhile, he remained at the tiller, occasionally shouting at the women struggling to row (which he forced them to do if they wanted to survive). Tensions culminated in a verbal altercation with Margaret Brown, who threatened to throw him overboard if he didn't stop his dark tirades.

One way or another, Hichens became the embodiment of indifference, and his name will forever remain among the most despised figures associated with the Titanic story.

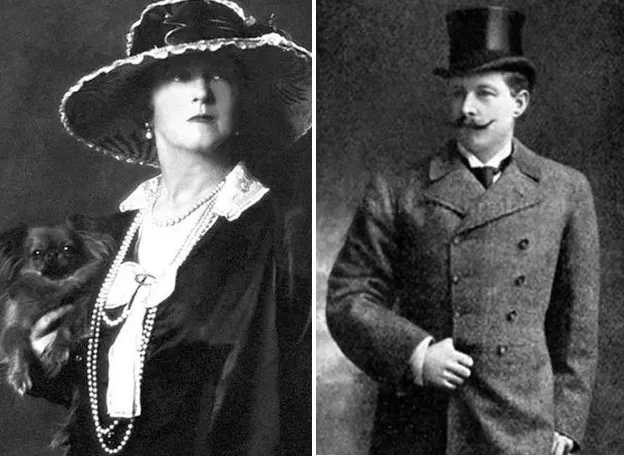

5. Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon – the aristocrat who "bought" his own safety

Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, a British aristocrat, was traveling on the Titanic with his wife, Lucy. When the liner began to sink, they boarded Lifeboat No. 1, one of the least crowded – only 12 people out of a capacity of about 40. This lifeboat could have saved 28 more people, including several children.

But the passengers and crew in Lifeboat No. 1 were predominantly men and Sir Cosmo's wife. Immediately after the rescue, rumors arose that Duff Gordon allegedly handed each of the rowers five pounds sterling to prevent them from returning to the sinking ship for more people. Duff Gordon himself claimed the money was not intended as a bribe, but as compensation for lost personal belongings and wages, as the rowers had lost their equipment and wages during the hasty evacuation.

Nevertheless, the public and the press perceived this gesture as morally questionable. Despite the rumors, the official British investigation found Duff Gordon guilty of any crime or direct attempt to interfere with the rescue, but the aristocrat's reputation was damaged.

Sir Cosmo's story became an example of how moral assessment of actions during a disaster sometimes leaves a far more lasting mark than formal accusations. For many, he forever remained a cynic, whose cold calculation and desire for self-preservation prevailed over compassion as thousands perished. Regardless, ordinary society (and even respectable men who considered his actions far from "gentlemanly") despised him for the rest of his days.