Talking tombstones of Amrum and Föhr (9 photos)

Can the dead talk? Not just talk, but tell stories.

About 60 kilometers north of Heligoland in the North Sea, off the west coast of Germany, lie the islands of Amrum and Föhr. Part of the North Frisian Islands, they are home to an interesting tradition known as "Sprechende Grabsteine" or "talking tombstones." Rather than being just plaques, these tombstones, scattered throughout the islands' various cemeteries, contain inscriptions that provide insight into the lives and histories of the deceased. Each tombstone is decorated with a carved image or scene representing the person's profession, achievements or significant events in their life.

Amrum Island

This tradition dates back to the 17th century, when Amrum and Föhr became important whaling centers. During this period, Dutch and English whaling ships stopped at the islands to recruit local crews. Many young and very young islanders joined these expeditions and, having grown up surrounded by water, demonstrated exceptional seamanship skills. Some even became harpooneers and captains.

Talking tombstones in the Church of St. Clemens in Nebel on the island of Amrum, Germany

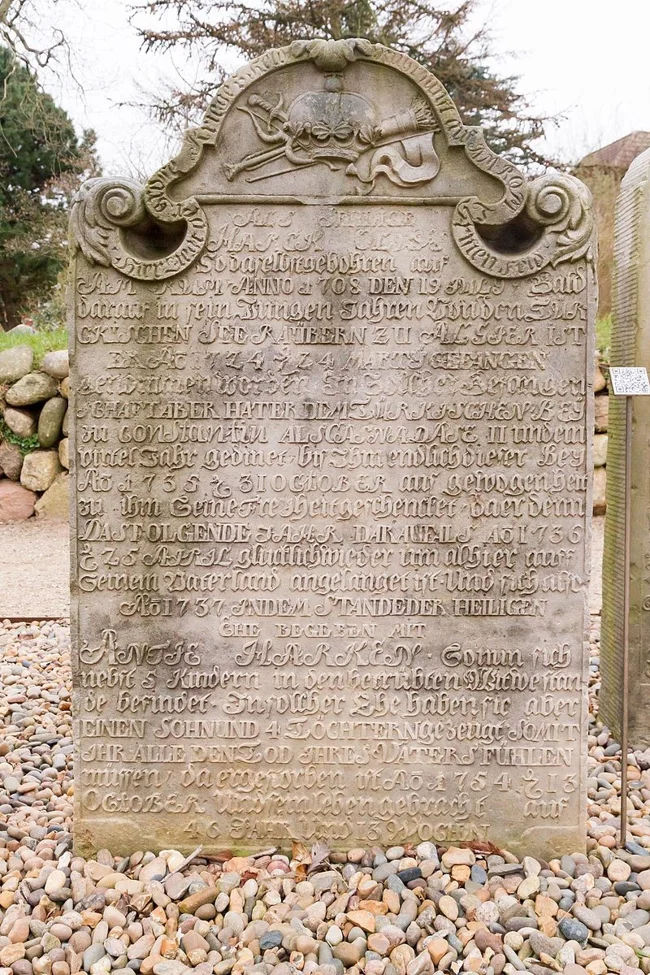

Upon their return home, these fearless sailors had many fascinating stories to tell, which were engraved on their graves after their departure for the heavenly abode. In addition to personal triumphs, the talking tombstone could contain detailed information about the deceased's origins, dates of birth and death, marriage, and number of children. Some inscriptions were so extensive that the back of the tombstone had to be used to accommodate the full narrative.

These talking tombstones were made using sandstone quarried from the remote hills of northern Westphalia or Lower Saxony and decorated with intricate carvings of brigs, skiffs and sloops. Initially, Dutch wood carvers hired from the mainland were responsible for creating these unique memorials. However, over time, local shipwrights and residents acquired the necessary skills in stonemasonry and eventually adopted the engraving process as well.

The most magnificent tombstones were once erected on the graves of islanders who took part in whaling expeditions to Greenland. Other finely carved stones marked the resting places of members of the upper class and wealthy families. However, these monuments were reserved for the wealthy, given their considerable cost. Each engraved letter alone cost around 3 gold marks – no small expense, considering that the average person earned around 10 gold marks a year. Meanwhile, during a successful whaling season, a ship's captain could bring home around 900 marks.

Hark Olufs's Gravestone

Therefore, less wealthy people often had simpler memorials, such as a red sandstone slab with only the basic birth and death information, or a modest wooden cross. The stark contrast of the tombstones reflected the socioeconomic inequalities of the time. Intricately engraved talking tombstones were reserved for those who could afford the expense, especially those whose lives were tied to the thriving whaling industry.

Depictions of different types of ships

The talking tombstones in Amrum and Föhr often feature intricate depictions of various ships, including fishing schooners, galliots, tjalkas, kofs, brigs, barges, whalers, and armed cargo ships. Contrary to the assumption that these carvings are dedicated exclusively to sailors, the ships symbolized a metaphorical journey through life. When ships were depicted anchored in a harbor, they symbolized the end of a life's journey. Examples of personalized carvings include the Dutch windmill on the tombstone of Erk Knudten, a sailor turned miller, and the man in Sunday suit on the inscription of Hark Knudten, a church minister.

Tombstone of the miller Erk Knudten

The symbolism also extends to the floral motifs on the tombstones, where the flowers are thought to represent a full and rich life. However, broken stems represent deceased relatives who passed away before them. These artistic and symbolic images on the tombstones provided a visual representation of the person's life and experiences.

Tombstone of mason Jan Peeters

In the 19th century, the islanders faced economic hardship, which led to a decline in the production of these characteristic, telling tombstones. By the early 1800s, fewer and fewer of these memorials were being made. The decline was further exacerbated by the Second Schleswig War in 1864. Amrum experienced a period of joint rule between Prussia and Austria, and then became part of the Kingdom of Prussia after Prussia's victory over Austria in 1866. Prussia was subsequently incorporated into the newly united German Empire in 1871.

The changing political landscape, coupled with changing aesthetic preferences, had a lasting impact on the fate of the talking gravestones. The Wilhelmine rulers, who came to power at the end of the 19th century, disdained the disorder in the old cemetery. In an effort to restore order, they replaced the winding paths with straight paths and installed several talking gravestones into the cemetery walls. Unfortunately, the elements gradually eroded the stones, causing some of the inscriptions to become illegible over time. Thus ended the era of the "Sprechende Grabsteine" tradition, leaving behind a unique but fading testimony to the rich maritime history and cultural heritage of the islanders.

Visitors to Amrum can see these tombstones in the cemetery of St. Clemens Church in Nebel. In Föhr, the talking tombstones can be found in the cemeteries of St. Lawrence Church in Süderend, St. Johann Church in Nieblum and St. Nikolai Church in Boldixum.