Dr. Cunningham's Delusion and His Steel Sanatorium (10 photos)

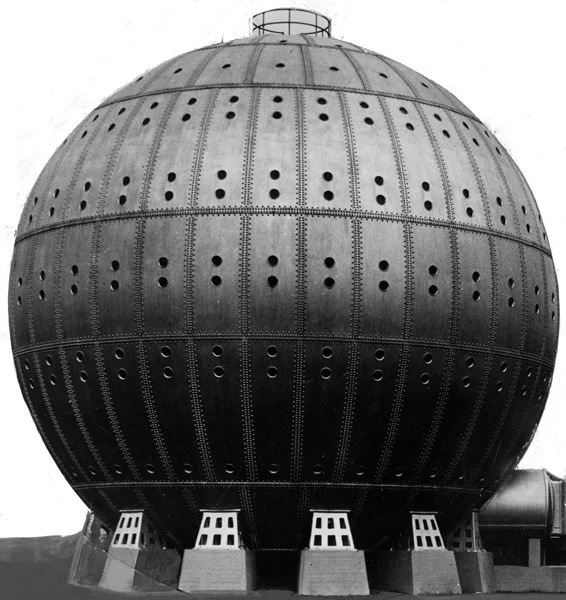

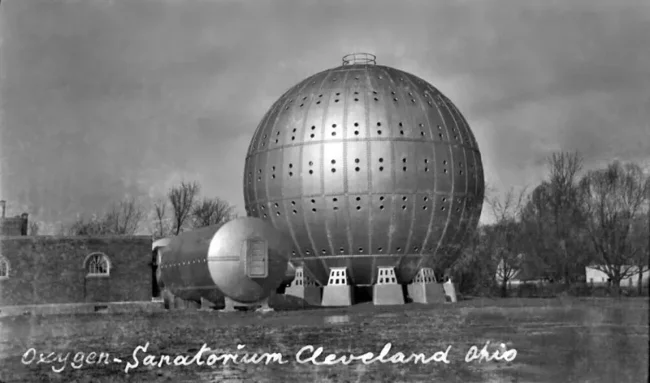

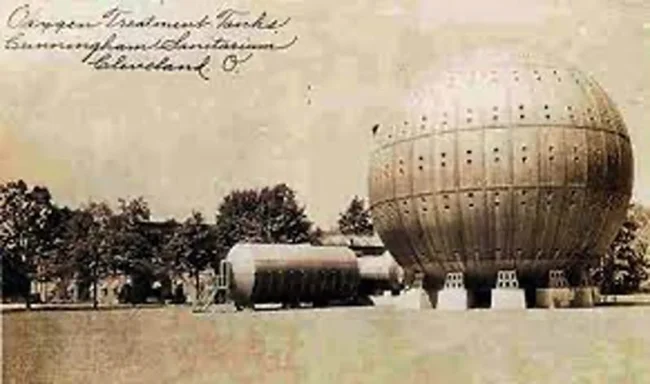

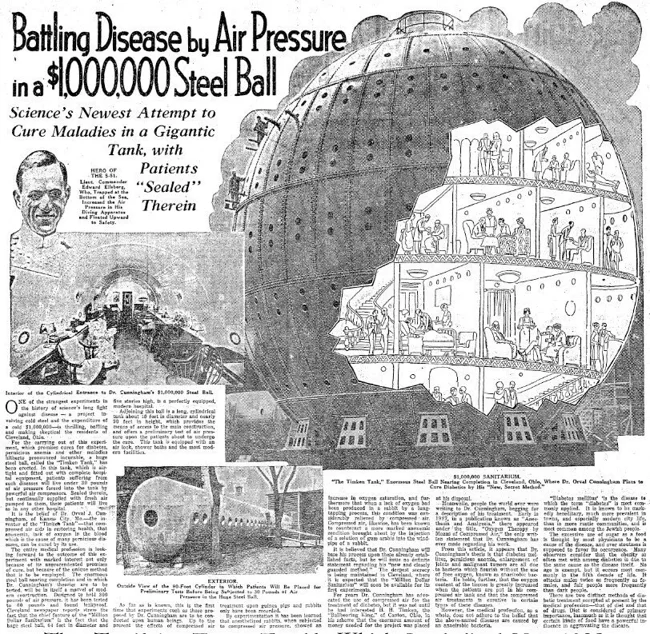

On the shores of Lake Erie in Cleveland, USA, there once stood a giant steel sphere, the height of a six-story building. Inside this 20-meter sphere were 38 rooms where Dr. Cunningham's patients spent two weeks in a compressed air atmosphere, breathing oxygen under pressure.

The doctor was convinced that excessive pressure saturates the body with oxygen and cures many ailments. This method is known as hyperbaric oxygenation.

The idea itself wasn't new. As early as 1664, the English physician Nathaniel Henshaw described the benefits of compressed air in his treatise "Aero-Chalinos" and is rumored to have built the first pressure chamber. However, it was Dr. Cunningham who became the leading advocate of this dubious therapy.

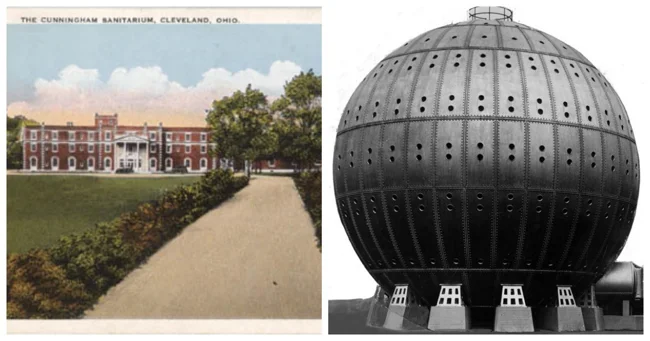

Front view of Cunningham Sanatorium

While working as an anesthesiologist at the University of Kansas, Cunningham noticed that patients with lung diseases often felt better after moving from high-altitude Denver to lower-altitude Kansas City. He mistakenly concluded that the more oxygen-rich air of the plains was to blame.

Spherical Hyperbaric Chamber

During the 1918 flu epidemic, Cunningham built his first hyperbaric chamber in Kansas City – a long cylindrical tank with beds for patients. Two cases of what seemed to be successful treatment of seriously ill pneumonia patients turned the doctor's head. He began promoting oxygen therapy as a panacea for everything from diabetes and cancer to syphilis and hypertension. His method was based on the false assumption that these diseases were caused by anaerobic bacteria that died in an oxygen-rich environment.

One of those converted to the new faith was millionaire Henry Timken (according to another version, his friend was treated). Inspired, Timken donated a then-exorbitant $1.5 million to build an entire hospital complex with a huge steel spherical pressure chamber on the shores of a lake in Cleveland. The location was chosen for its seclusion and picturesque views.

Inside, the steel sphere, reminiscent of an industrial gas tank, was finished with the luxury of an expensive hotel and comprised five floors of private bedrooms, relaxation areas, and comfortable bathrooms. The heart of the complex was a powerful air conditioning system: three compressors, two steam boilers, a 27-ton ammonia refrigerant that acted as a dehumidifier, and a filter system. This system allowed for pinpoint control of not only the pressure but also the temperature, humidity, and air circulation using automatic thermostats.

The sanatorium opened in 1928, but that same year, the American Medical Association (AMA) Bureau of Investigation published a scathing article, declaring that Cunningham's methods "showed a stronger admixture of commercialism than scientific medicine."

Dining Room

In 1934, at the height of the Great Depression, Cunningham was forced to sell his hospital to James Rand Jr., son of the co-founder of Remington Rand and his former protégé. Rand renamed the complex the Ohio Institute of Oxygen Therapy, but failed to attract patients. Just two years later, he resold the business. The new owners abandoned oxygen therapy and attempted to convert the balloon into a regular hospital, but this venture also quickly failed.

Interior Corridor

The building was abandoned and purchased by the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland in 1942. The steel sphere-shaped sanatorium, a symbol of the medical escapade, was dismantled for scrap metal for the war industry.

Dr. Cunningham died in 1937. His methods were never scientifically proven to treat the diseases he promised to cure. However, over the years, some of his approaches, purged of quackery, have found narrow but important applications in modern medicine—for example, in the treatment of decompression sickness.