A bridle for the obstinate as an instrument of male "justice" in the Middle Ages (8 photos)

How did medieval husbands discipline their overly talkative wives?

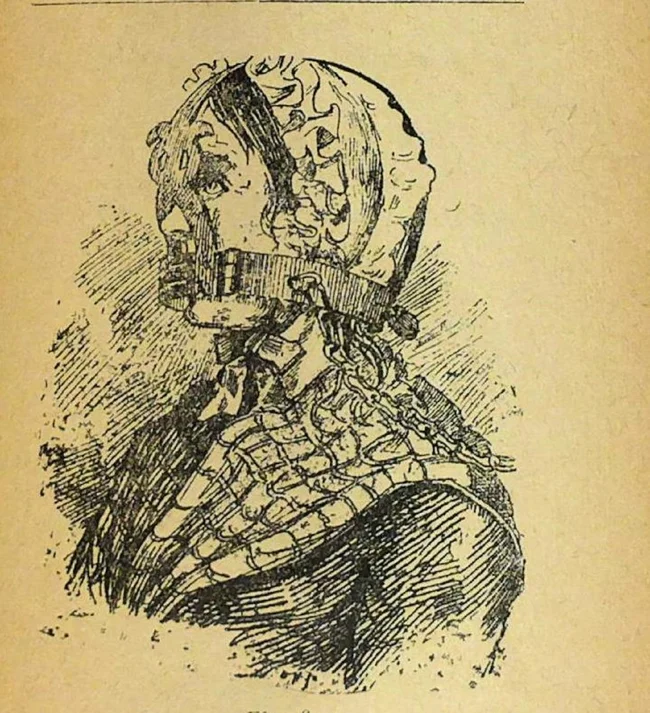

The answer is simple and terrifying. They used special muzzle masks. This instrument of torture and public humiliation, known as a shrew's bridle (witch's bridle, gossip's bridle, or shame mask), was used primarily in England and Scotland in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The mask could be placed on a woman who constantly grumbled and nagged those around her, disturbed the peace of her neighbors with gossip, swearing, and inappropriate behavior.

Women who quarreled with neighbors, contradicted their husbands, and argued with priests were a serious concern for men in society. It's unknown whose twisted mind first conceived of taming a woman with a bridle, but the idea quickly found supporters.

A bridle for the obstinate consisted of an iron muzzle and a frame that completely encircled the head. When this device was put on, the person could neither eat nor speak. Some bridles were equipped with spikes that entered the mouth when the device was locked. The slightest movement of the jaw caused excruciating pain to the victim, piercing the roof of the mouth and tongue. It was barbarically cruel.

This type of bridle was first used in Scotland in the late 16th century as a punishment for witches. Later, in England, it was used to "tame" quarrelsome women and other troublemakers. Many communities had their own traditional punishments for talkative wives. The most common was the "dipping chair," where the victim was tied to a chair and lowered into a river or pond. But some preferred the bridle.

Being shackled in irons was not only painful but also deeply humiliating. In Scotland, a masked woman was often paraded through the streets, sometimes by her own husband. Obstinate women were also punished by being chained to the pillory. These actions were meant to clearly demonstrate the consequences of any disobedience or harsh words.

Bridles for the unruly remained in use for over a century, and in other parts of Europe, such as Germany, they were used in workhouses until the early 19th century.