Marley's car - 14 giant wheels that made the Seine work for Versailles (9 photos)

Water features are one of the most impressive features of the gardens of the Palace of Versailles near Paris. There are fountains, cascading waterfalls, quiet ponds and long canals.

Not far from the palace, near two water parterres, are sculptures depicting fights between wild animals: a lion defeating a boar, a tiger taming a bear, and a hound bringing down a deer. Water gushes from the mouth of each animal into a pool. The Dragon Fountain (actually the Python snake) is one of the oldest in Versailles, its jets soar 27 meters. And the most majestic, the Latona Fountain, illustrates a scene from Ovid's Metamorphoses: the four-tiered composition is decorated with figures of frogs, lizards and turtles.

From the very beginning, providing the fountains with water was a serious problem for the architects. The nearest source, the Seine River, was ten kilometers away, and the palace itself was located at an altitude of almost 150 meters above sea level. The solution was proposed by a young and ambitious lawyer, Arnol de Ville. Despite his lack of engineering education, he had already built a hydraulic machine for pumping water from the river in Belgium, at his estate, Château de Modave. For Versailles, de Ville developed a similar, but much larger project.

The Latona Fountain in the Gardens of Versailles

Louis XIV was so impressed that he commissioned him to create a machine on the Seine that would supply water not only to the gardens, but also to the Marly Palace under construction.

The Fountain of Apollo

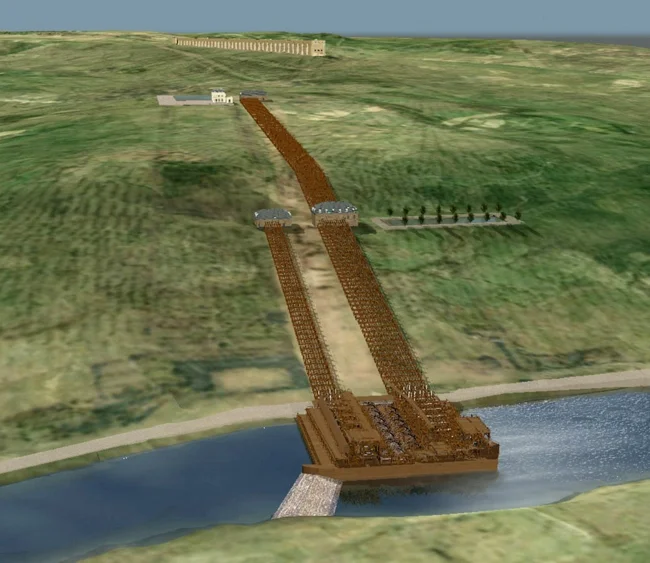

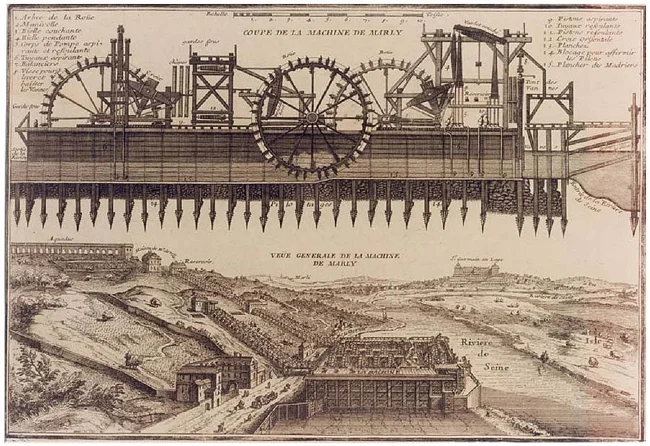

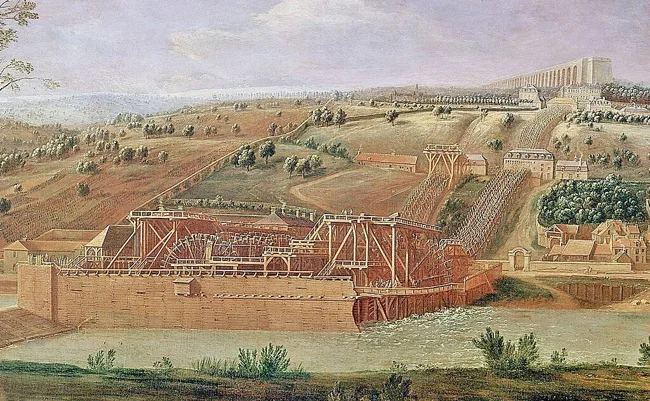

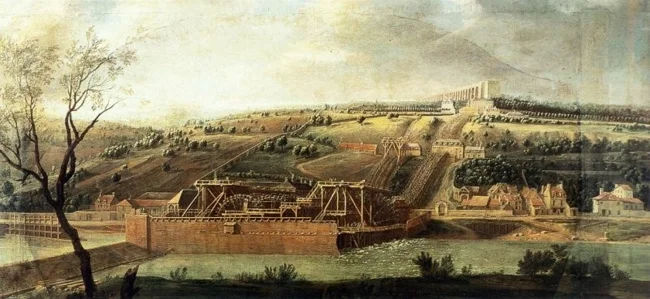

In 1681, construction began on an unprecedented hydraulic pump, the Machine de Marly, seven kilometers north of Versailles. With the help of carpenter and mechanic Rennequin Sualem, de Ville erected a gigantic structure: 14 wheels, 9 meters in diameter, each with two cranks. One set in motion pistons that pumped water into pipes and raised it to the first reservoir. The other controlled a system of levers that transmitted force up the slope to the next reservoir. From there, the water flowed to the top of the water tower, and then by gravity through an aqueduct to Versailles and Marly.

The Marly Machine

Partially submerged in the Seine, the machine required more than 100,000 tons of wood, 17,000 tons of iron, 800 tons of lead and cast iron. Wood for the platform, wheels, dams and buildings was taken from the surrounding forests. Iron rods came from Nivernais and Champagne, and cast iron pipes were made in Normandy.

At full capacity, the Marly Machine pumped an average of 3,200 cubic meters of water per day — more than all of Paris consumed. But even that was not enough for the Versailles fountains: at half capacity, they required four times as much water, so restrictions had to be introduced.

The complexity of the mechanism made its maintenance extremely labor-intensive. Sixty people monitored the operation of the wheels and the supply of water. Breakdowns were frequent, and repairs were expensive.

The machine worked for 133 years until it was modernized in 1817, increasing its capacity to 20 thousand cubic meters per day. Most of the structure was replaced, and the wheel pumps gave way to steam engines. By the middle of the 19th century, almost nothing remained of the original structure. Today, on the hillside, you can see the overgrown walls of the reservoir, and several buildings have survived by the river - two administrative buildings and one, where a steam pumping station was located since 1825.