Tunnel under the Thames: the world's first underwater artery (7 photos)

In the early 19th century, London was bustling as one of the world's busiest river ports, and its ancient stone bridge across the Thames, which had stood for six centuries, was barely able to cope with the influx.

Like many medieval bridges, it was lined with houses hanging over the roadway, turning it into a dark corridor. Despite its width of 8 meters, only half was left for traffic - and this narrow strip was shared between carts, carriages and pedestrians moving in both directions. At rush hour, the crossing could take up to an hour.

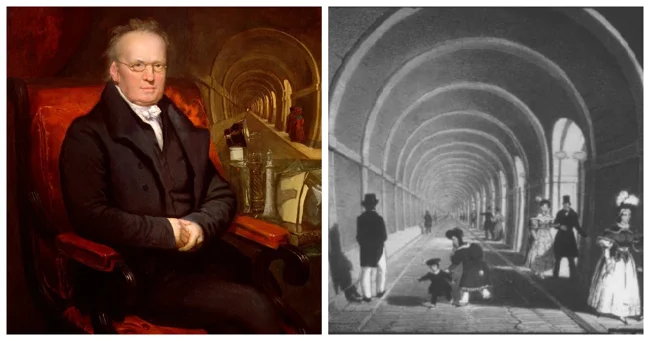

Banquet in the Thames Tunnel, by George Jones, 1827

It became clear: the city needed a new crossing. But this time, not a bridge, but a tunnel built under the river.

Underground Breakthrough

Marc Brunel

There have been previous attempts to break through the Thames. In 1799, engineer Ralph Dodd failed to connect Gravesend and Tilbury. Then, in 1805, a team of Cornish engineers began digging between Rotherhithe and Wapping, but the loose, water-saturated clay proved too much for them – used to hard rock, they were unable to stop the torrents pouring into the tunnel. The project was abandoned, declaring such an undertaking hopeless.

However, Marc Brunel, a talented French engineer who fled to Britain from the revolution, thought differently. Even earlier, he proposed to Emperor Alexander I to build a tunnel under the Neva in St. Petersburg, but he preferred a bridge. Now Brunel took on the Thames.

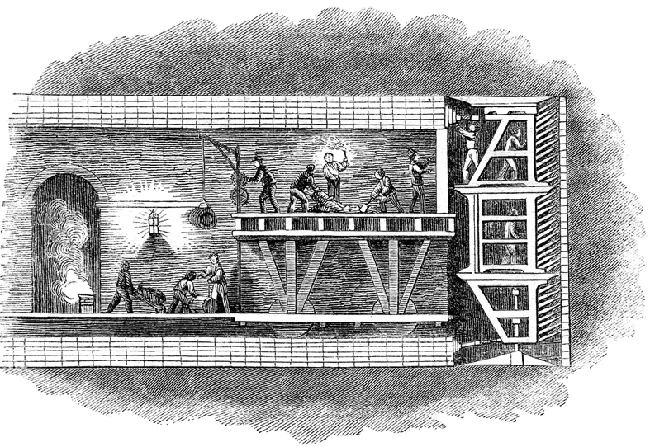

A shield used during construction

He analyzed the mistakes of his predecessors and invented a method that determined the future of tunnel construction for two centuries - a tunneling shield. This temporary structure, pressed against the wall of the mine, protected workers from collapses. It is said that Brunel got the idea from a shipworm that gnaws passages in submerged timber, a specimen he once saw in the docks.

Brunel's Shield

A scale model of a tunneling shield at the Brunel Museum in Rotherhithe

The shield resembled a giant iron grate with 36 compartments in three tiers. Each compartment was closed at the front by movable shields. Workers took them off one by one, removed the soil to a given depth, then returned the shield to its place and strengthened it. After all sections had been processed, the entire machine was moved forward, and the freed space was lined with bricks.

But even with this revolutionary method, progress was at a snail's pace - only 2.5-3.5 meters per week. The shield protected against collapses, but not from the dirty water mixed with sewage seeping from above. In the stuffy, miasma-saturated tunnel, workers suffered from diarrhea, headaches, and even temporary blindness. The pumps pumped out water without stopping, but when they broke, the tunnel was flooded by a meter or more.

In 1827, the worst happened: the workers made a hole in the riverbed, causing a raging flood. Brunel's son, Isambard Kingdom, went down in a diving bell to plug the hole with bags of clay. A year later, another breakthrough took the lives of six people, and the money ran out. The tunnel was sealed.

It was only seven years later that Brunel found the money and created an improved shield that could withstand the pressure of the Thames. Another six years of hard labor - and in 1841 the tunnel finally reached Wapping.

Triumph of the engineers

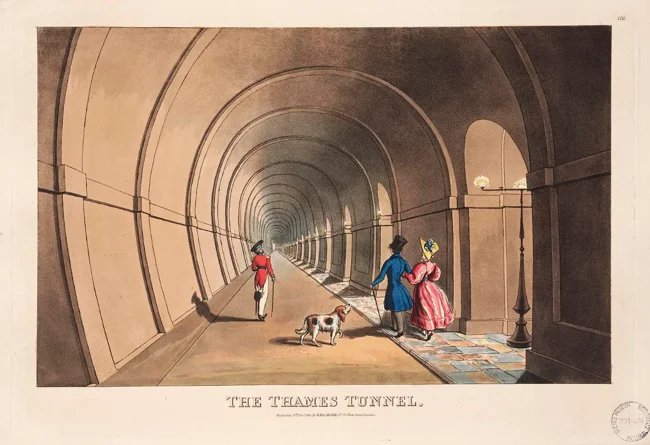

Inside the tunnel, 2010

The construction cost half a million pounds - many times more than expected. The idea of making entrances for carts was abandoned due to the cost, and at first the tunnel served only pedestrians. But it became the highlight of the season: two million visitors a year paid a penny for the opportunity to walk through the underwater wonder.

In 1865, the tunnel was bought by the East London Railway, which converted it for trains. Later, it became part of the underground network and operated until 1962.