Alisa Kiteler: an insidious poisoner or a victim of a slander? (9 photos)

One of the most common fairy tale plots is the confrontation between a poor orphan and an insidious stepmother pursuing her own selfish interests.

In life, such cases are not so rare. But not everything in reality is so simple. And this story is a vivid example of this.

Witchcraft accusations, trials, and forced confessions obtained under torture led to the deaths of approximately 100,000 people in Europe between 1400 and 1775. In France, England and Germany, healers, the mentally ill, witches, single women over 40, and a small number of men were executed for heresy and witchcraft, and many were burned at the stake.

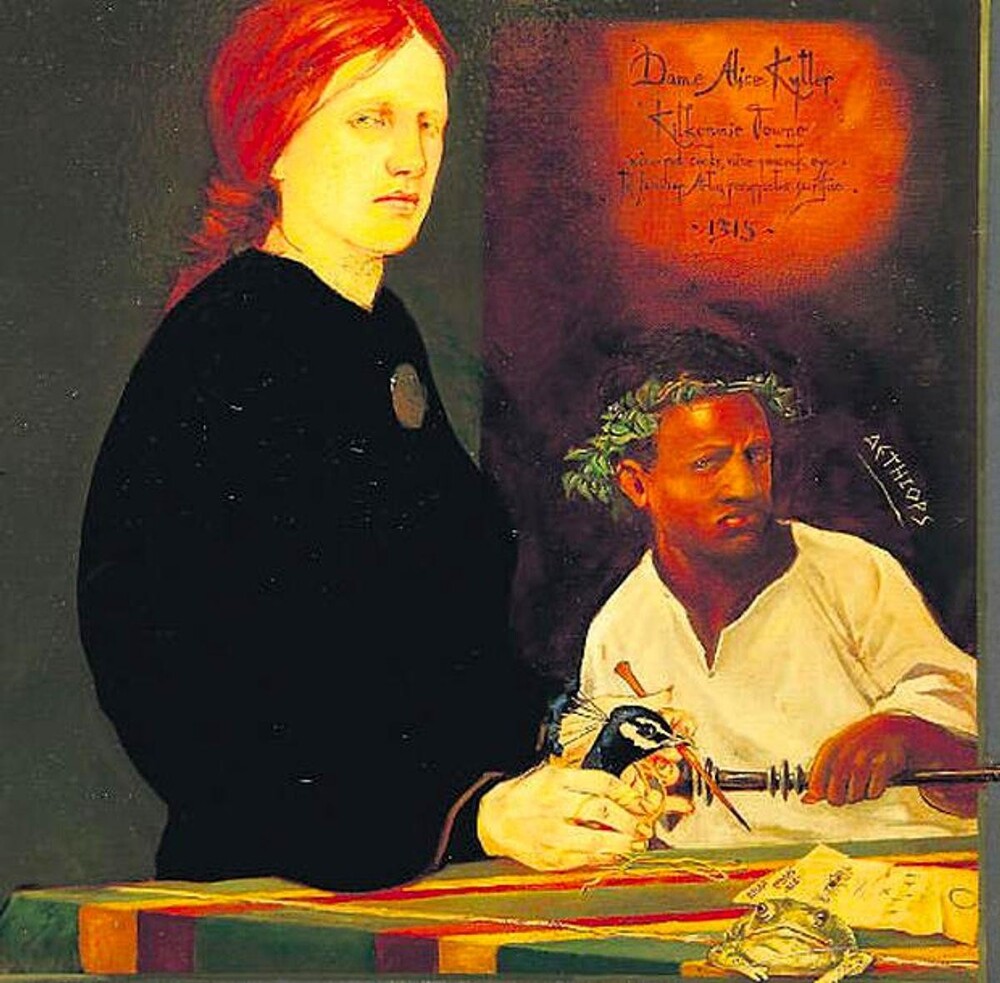

But before Europe saw most of its witch trials, Ireland became the first country to record a witch accusation and trial in 1324. Ireland's first witch was Alice Kyteler, a woman who became very wealthy and whose husbands had a sad tendency to die suddenly. Who was this woman, and why was she considered a witch?

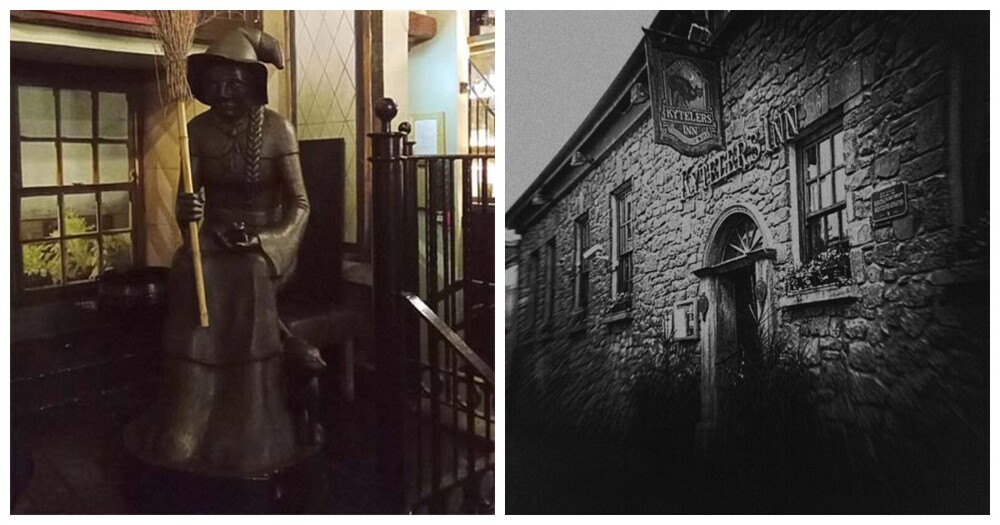

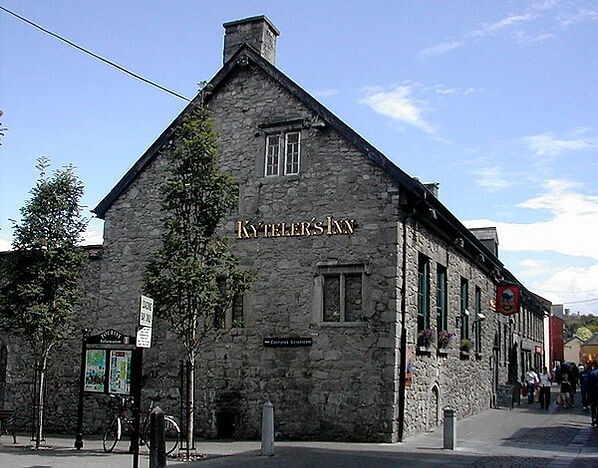

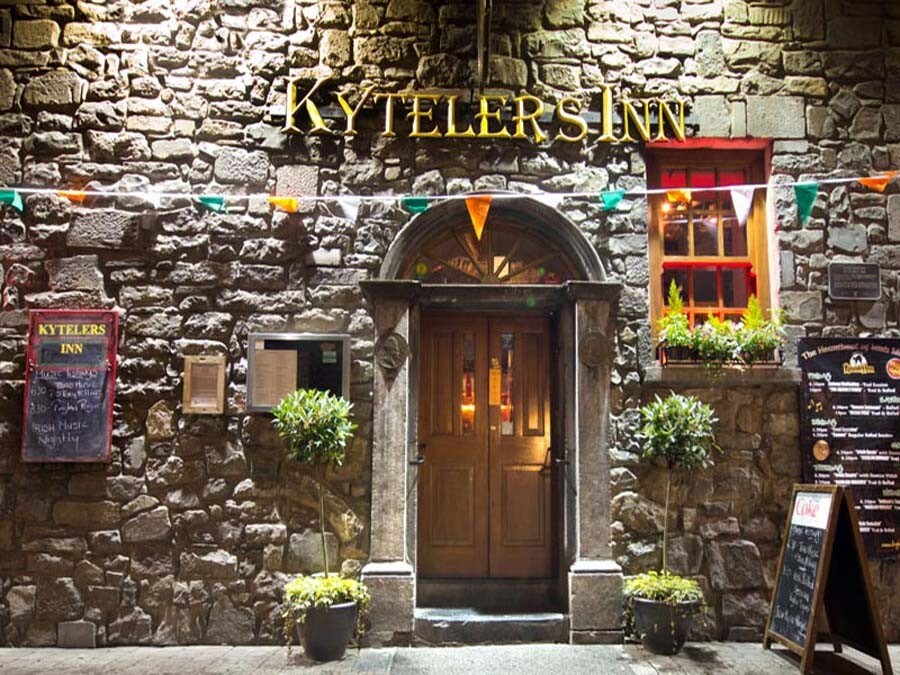

The hotel that belonged to Alice

Alice Kyteler became the first person in history to be convicted of witchcraft in Ireland. She was born in 1263 in County Kilkenny into the family of a Flemish merchant.

Alice married four times during her life, and her stepsons accused her of murdering their husbands after she demanded her share of the inheritance.

Alice Kyteler's first husband was William Outlaw, to whom she was married from about 1280 to 1285. William was a wealthy merchant and moneylender.

The couple had a son, who was named after his father, and possibly a daughter, who may have been named Rose. But no other information has been preserved about her. The woman did not have children from any of her next husbands.

William Jr. and Alice inherited William Sr.'s business after his death. Alice Kyteler's second husband was a man named Adam Bland, whom she married in 1302. Like her first husband, Adam was a very wealthy moneylender.

The couple had no children together, but Alice became the stepmother of Adam's children from a previous marriage. After Adam's death, the widow remarried.

The third husband was Richard de Walle. Richard came from a prominent family in County Tipperary and was a wealthy landowner, who in turn died in 1316. Shortly thereafter, Alice Kyteler sued one of her stepsons, also named Richard, for widow's grants - those possessions that, after the death of a lord, passed not back to his lord, but to his widow. The law stated that after the death of her husband, the widow was entitled to a third of the property as her own source of income.

Alice married her fourth husband, John le Pour, in the same year that her third died. The couple were married from 1316 to 1324. As was the case with the others, Alice again became a stepmother to her husband's children from a previous marriage.

While Alice Kyteler and John le Pour were together, the Bishop of Ossory, Richard de Ledrede, attempted to arrest Alice on suspicion of murder and "other offences". John stood up for his wife and defended her.

The man did not believe the words of the other stepsons who accused Alice of murder. That was until John himself fell ill with a disease called “wasting disease.” John suspected that his wife had poisoned him, but did nothing until his death in 1324.

After John le Pour's death, all the adopted children became angry that Alice got the money they were claiming. The children believed that Alice and her son William had supernatural powers and used them to deceive and bewitch their fathers, kill them and get money.

At least that's what it claims. Those who are more cynical and suspicious may assume that the children, who found themselves powerless due to the appearance of a new wife, had a clear motive to slander Alice. This behavior is nothing new.

The children turned to the Bishop of Ossory, who happily agreed to organize an investigation to finally bring Alice Kyteler to justice. Witnesses were drawn from local residents, but again questions of bias were raised as many were believed to be in debt to the debtor.you and William. The stepchildren also testified against the stepmother.

Alice and her son William Outlaw Jr. were accused of being powerful sorcerers and heretics, along with ten others who were counted as their accomplices. She was tried for witchcraft and causing the death of innocent Christians.

Alice and her "accomplices" were said to have prepared powders and potions from all sorts of vile ingredients, which, when mixed in the skull of a headless robber and surrounded by candles of human fat, and accompanied by terrible incantations, brought disease and death.

If this were not enough, it was claimed that in order to make their spells and potions even more effective, all members renounced Christianity and, going further, turned to demons for help, to whom they sacrificed animals. Alice was accused of having her own personal demon - an incubus, with whom she entered into an intimate relationship.

It was thanks to the incubus that Alice was able to become so rich. Her wealth at the time of the trial was called unheard of, because for a woman of humble birth to be rich and have a profitable business was, as it was believed, impossible without the help of demons.

Nonsense, of course. Especially against the backdrop of mixing religion and law. As well as a list of charges.

After the trial, Alice's servant, Petronilla de Meath, was subjected to corporal punishment, torture and was burned as the first witch in Ireland. But Alice herself turned out to be more prudent and managed to escape.

She disappeared either in England or in Flanders, and no other records of Alice survived. The court deprived her of her possessions, but the woman saved her life and lived the rest of it, albeit in a foreign land, but alive and healthy.

Statue of Alice Kyteler and her maid Petronilla in Kilkenny, Ireland

Were any of the allegations true? There were many marriages and many early deaths, and there is no doubt that Alice Kyteler became rich through her inheritance. All this really leads to suspicion.

Alice Kyteler may indeed have poisoned one or more of her husbands. But there was no hard evidence of this. The status of the main suspect - killer or victim - in this story, which became the forerunner of the subsequent persecution of witches, remained a mystery.