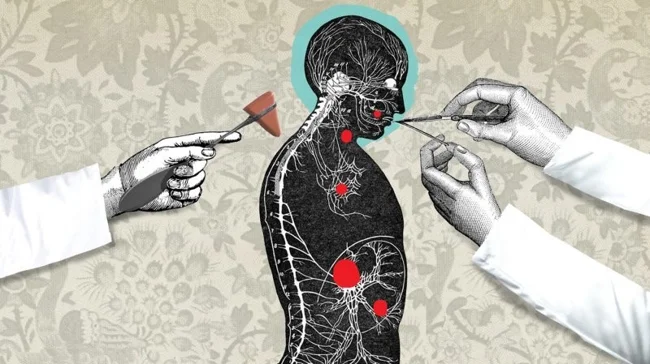

Dentist from the Underworld: How Dr. Cotton Treated Mental Illnesses by Removing Patients' Organs (6 photos)

This strange image of a mouth isn't a still from a horror movie or the result of a bad fall or fight, but the result of a doctor's obsession with an absurdly bizarre theory.

A theory that has crippled thousands of his patients for life.

Illustration of a mouth with extracted teeth from Cotton's book

Dr. Henry Cotton served as medical director and chief physician of Trenton State Hospital, a large mental hospital in New Jersey. Before returning to the United States and being appointed to this position at the young age of thirty, Cotton studied psychiatry in Europe under two legendary figures of the time, Emil Kraepelin and Alois Alzheimer. He was also a student of Dr. Adolf Mayer of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

All of these men were pillars of the field of psychiatry, especially Mayer, who was one of the first to recognize that mental problems were problems of the human personality, not the brain. Mayer also understood that a person's activity and mental health were interconnected, and he advocated therapy, community services, and changes in a person's daily life, environment, and habits as part of treatment.

Adolf Mayer

Despite his revolutionary teachings, which have become firmly established in modern psychiatric theory and practice, Mayer also nurtured the idea that mental illness could be caused by bacterial infection. This was based on the observation that patients with high fevers often become delirious or hallucinate.

Henry Cotton was fascinated by the idea that microbes were the root of all mental illness. In 1913, when reports confirmed that the bacterium that causes syphilis caused brain damage that led to psychiatric symptoms and, in the most severe cases, dementia, Cotton was inspired. Soon after, he began applying his theories to patients at Trenton State Hospital. At that time, penicillin was still a decade away, and the only way to eliminate the infection was surgical removal of the infected organ.

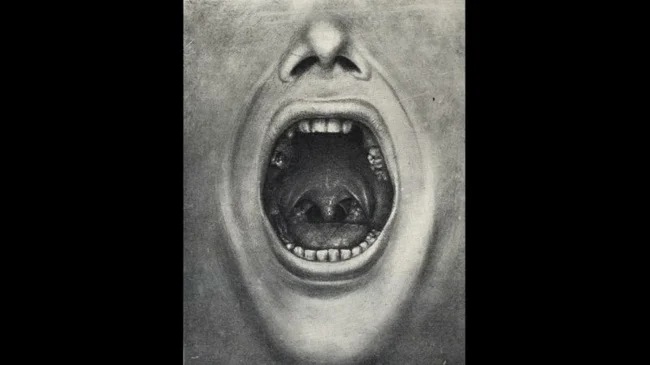

Portrait of Henry Andrews Cotton

Cotton attacked the teeth first and gradually moved on to other organs. The mouth, he reasoned, was the most obvious hiding place for germs. So he began by removing infected teeth, impacted teeth, teeth with decay, and abscesses. He even had his own teeth, as well as those of his wife and two sons, extracted as a preventative measure to avoid the risk of infection. When tooth extractions failed to cure his patients, he redoubled his efforts, removing their tonsils and sinuses in the process. If a cure still failed, other organs were suspected of harboring infection. Soon, patients were losing spleens, colons, testicles, ovaries, gallbladders, and other organs.

Of every three patients operated on by Cotton, one died. Cotton attributed the deaths to the patients' poor physical condition, caused by chronic psychosis. Among survivors, Cotton claimed a high success rate—85 percent—a statistic that earned him much praise from the scientific community. Desperate for relief, many wealthy men and women suffering from mental illness flocked to Trenton seeking Cotton's miraculous cures. However, many had to be literally dragged into the operating room, as the patients screamed and fought back. Sometimes, their families weren't even informed of the interventions.

New Jersey State Mental Hospital, Trenton

Meanwhile, at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Dr. Adolph Meyer commissioned Phyllis Greenacre, a newly hired staff member, to conduct a study evaluating Cotton's work in Trenton, hoping to receive a glowing report on her former student's work. Greenacre was overcome with a sense of gloom upon entering Trenton. The facility had "that sour, fetid odor so characteristic of mental hospitals," she wrote in her report, and she found Cotton himself "incredibly odd."

Greenacre was most shocked by the patients' appearance and behavior. Their faces were sunken, and their speech was slurred, as none of them had any teeth left. Greenacre discovered that the hospital records were chaotic, and the figures Cotton so often used to demonstrate the effectiveness of his methods didn't add up. Greenacre discovered that very few patients actually recovered, and that those who did had no connection to the operations, and that the death toll was significantly higher than Cotton admitted—almost half.

Unfortunately, Greenacre's months of work invested in her investigation were wasted. When Adolf Mayer read Greenacre's devastating report, he was shocked and, trying to save Cotton's career, refused to publish her findings.

Cotton resigned from his post at the State Hospital and opened his own private clinic in Trenton, where he continued his horrific experiments on patients. By the time he died suddenly of a heart attack on May 8, 1933, he had killed hundreds. Mayer wrote a flattering obituary for him, despite knowing that Cotton was responsible for the deaths of countless patients. Cotton's own sons also fell victim to this obsessive physician. Both committed suicide in middle age.