The Edwin Smith Papyrus: An Ancient Surgery Textbook Ahead of Its Time (6 photos)

In 1862, American Egyptologist Edwin Smith purchased an ancient scroll from a dealer. He couldn't decipher it, but he sensed he was holding something important and valuable.

The papyrus remained with him until his death in 1906, after which Smith's daughter donated the manuscript to the New-York Historical Society. It was there that the true value of the document now known as the Edwin Smith Papyrus was first realized.

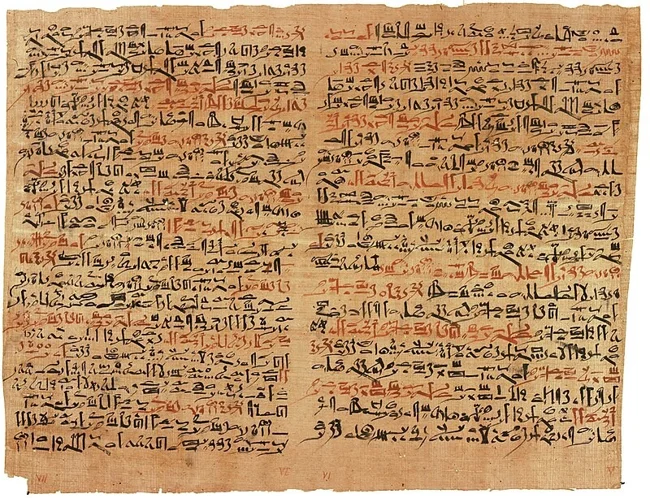

Folks VI and VII of the Edwin Smith Papyrus in the Rare Book Room of the New York Academy of Medicine

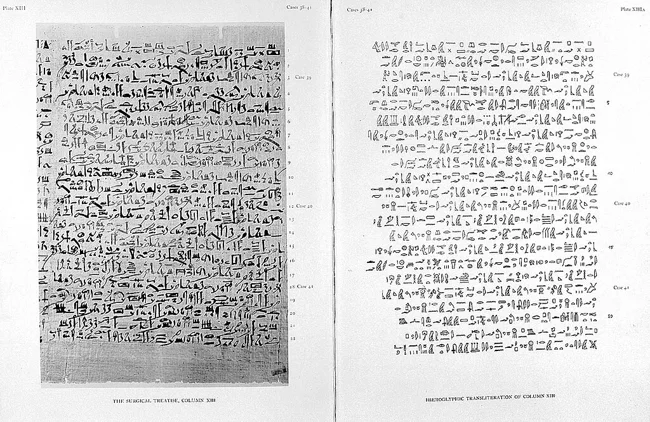

This medical treatise is the world's oldest textbook on surgery. It was created around 1600 BC, but careful examination of the script revealed that it was merely a copy of an older work, believed to have been written between 3000 and 2500 BC. The scribe who made the copy in the 17th century BC made a number of errors, some of which he later corrected in the margins. He ultimately set the scroll aside and left it unfinished, and the reason for this will forever remain a mystery.

Even in its unfinished form, the Edwin Smith Papyrus caused a sensation, as it demonstrated for the first time that the ancient Egyptians possessed a knowledge of anatomy and medicine that far exceeded previous understanding. Most importantly, it demonstrated that the Egyptians' understanding of traumatic injuries, which the papyrus devotes so much attention to, was based on observed anatomy, not magic or potions.

This papyrus likely served as a manual for military surgeons. It describes 48 wounds and injuries, including lacerations, fractures, dislocations, and tumors. Each case is presented in a format remarkably close to modern medical standards. First comes the patient's history and physical examination, which includes checking the pulse, examining the wounds for inflammation, and assessing the general appearance, such as eye and facial color, the nature of nasal discharge, and the stiffness of the limbs and abdomen.

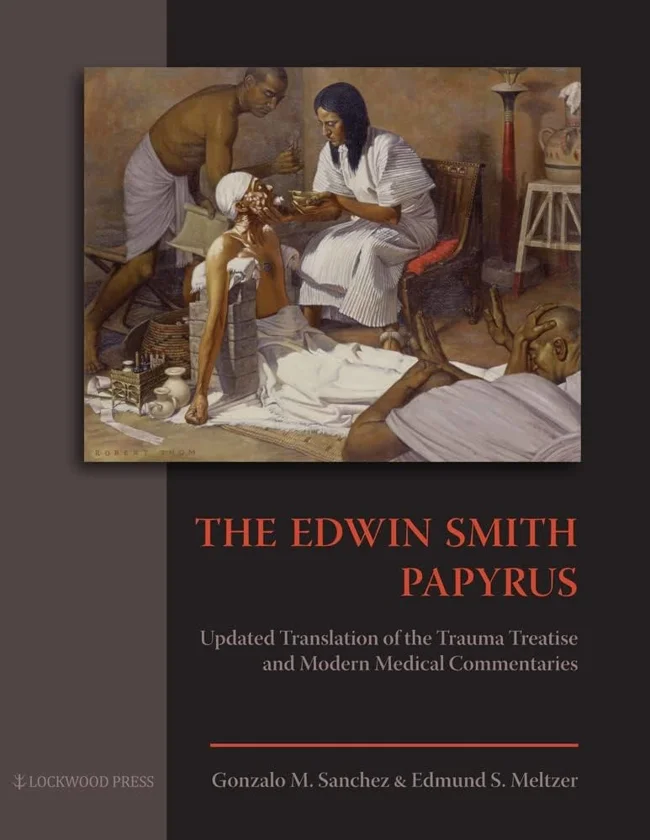

Egyptologist Edwin Smith

Following the examination, a diagnosis and prognosis are made. The doctor then assesses the patient's chances of survival by classifying the injury into one of three categories: "a disease I will treat," "a disease I will fight," and "a disease that should not be treated." Finally, treatment options are offered, which may include closing wounds with sutures and bandages, fixing broken bones with splints, preventing and treating infection with honey, and stopping bleeding with raw meat, demonstrating knowledge of antiseptic methods and antibiotics.

Brest edition (1930): photograph of the original papyrus on the left page, transcription of hieroglyphs on the right page

The Edwin Smith Papyrus also contains the first-ever descriptions of cranial sutures, meninges, the outer surface of the brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and intracranial pulsation. The Egyptians understood well that damage to certain parts of the brain could affect bodily functions, causing conditions such as paralysis. The document establishes a connection between the location of a cranial injury and the side of the body affected, and also notes that vertebral fractures impair motor and sensory functions.

The papyrus demonstrates that the Egyptians possessed an impeccable knowledge of human anatomy. It describes the heart, its vessels, the liver, spleen, kidneys, hypothalamus, uterus, and bladder, although the physiological function of each organ was not fully understood. They knew that blood circulated through the body through vessels, four millennia before William Harvey discovered the circulation of the blood, but they did not understand how.

Another thousand years passed before our knowledge of the human body was further enhanced by the works of ancient Greek physicians such as Herophilus, Erasistratus, and Hippocrates. Yet, some procedures described in the papyrus demonstrate a level of medical knowledge surpassing even that of Hippocrates. Alas, the full scope of the ancient Egyptians' medical knowledge will remain a mystery to us.