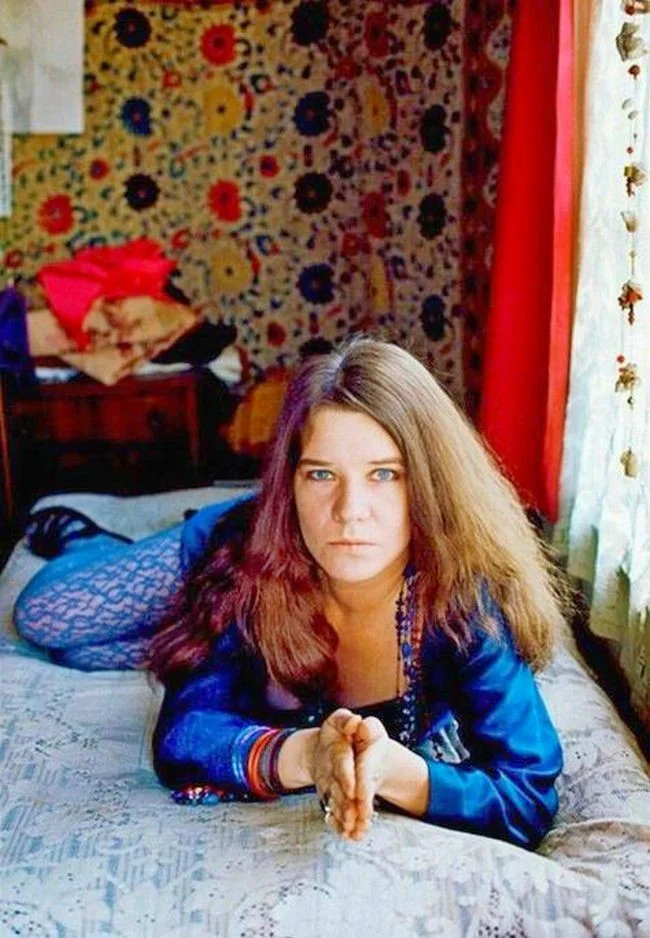

55 years ago, Janis Joplin passed away.

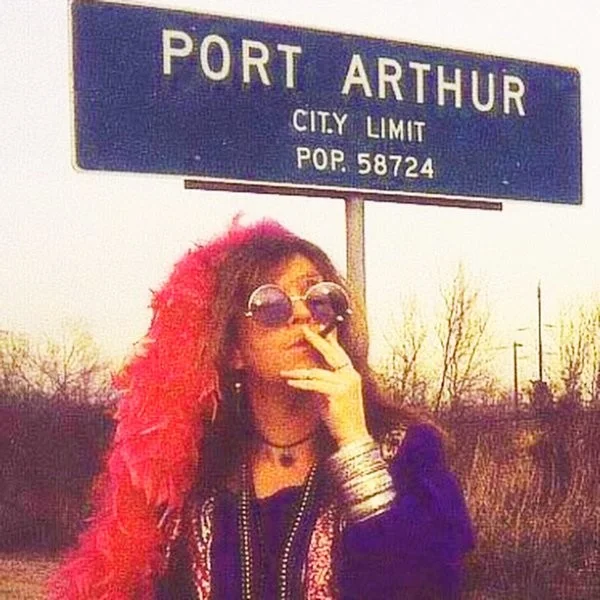

American blues-rock singer Janis Lyn Joplin was born on January 19, 1943, in Port Arthur, Texas, to Seth and Dorothy Joplin. Her mother, performing in college musicals, turned down an offer to pursue a professional career. After graduating from college, she moved to Amarillo, Texas, where she got a job at a local radio station, where she met her future husband. The couple moved to Port Arthur, where Seth got a job at an oil refinery for Texaco, a subsidiary of Chevron. Six years after Janis's birth, they had a daughter, Laura, and then a son, Michael.

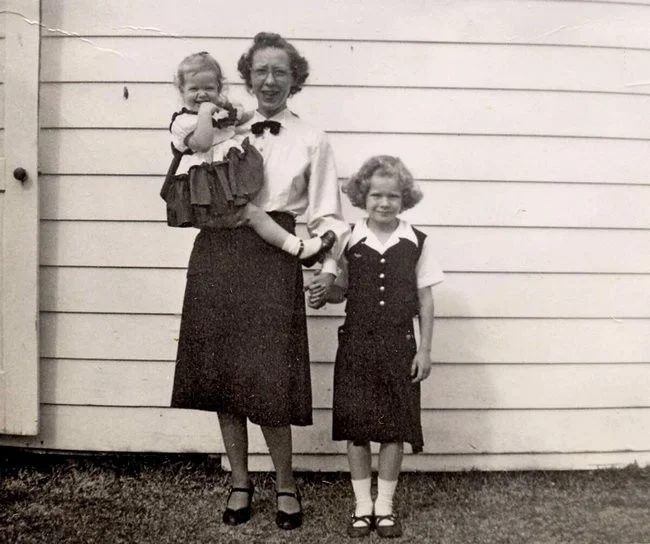

Janis Joplin with her mother and sister Laura

Janis's love of music was passed on to her by her parents. As her brother and sister later recounted, the elder Joplin was a "closet intellectual": he read Dante and listened to classical music rather than country music, as was common in South Texas, and he taught his children to "question the true reasons for things." Their parents didn't force their musical preferences on them, but their mother often demonstrated her vocal technique.

"On Saturdays, when we started cleaning the house, Mom would blast Broadway musicals at full volume, and the three of us—she, Janis, and I—would work, singing at the top of our voices" (from L. Joplin's memoirs).

Janis Joplin with her family

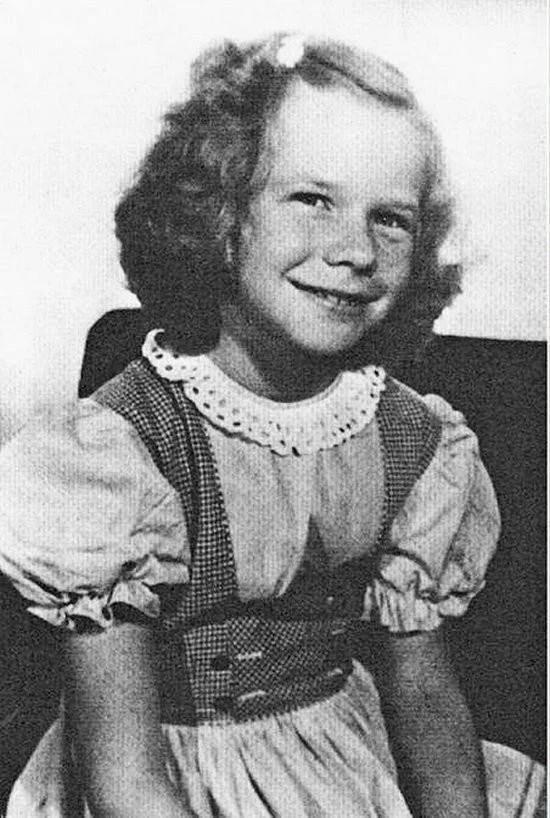

Janis was a smart, precocious girl. И страсть к творчеству проявилась у неё с детства: это началось с живописи, причём, с преобладающими библейскими сюжетами. БОльшую часть свободного времени она проводила в церкви или в местной библиотеке. Но так же с удовольствием вызывалась участвовать и во всевозможных благотворительных мероприятиях. Родители были довольны, что Дженис с ранних лет проявляла самостоятельность и независимость.

В школе Томаса Джефферсона/Thomas Jefferson High School (Порт-Артур) девочка была примерной ученицей и соответствовала общественным нормам. Однако подруг у неё не было: общалась она исключительно с парнями. По словам Лоры, вскоре стало ясно, что по интеллекту Дженис намного превосходит сверстников. Кроме того, она всегда откровенно высказывала всё, что думает, а поскольку, по её собственным словам, «не ненавидела ниггеров», стала изгоем в школе, где расистские настроения, как и везде на Юге, были нормой.

"I don't think you could call me a civil rights activist. In those parts, that was the term for anyone who thought it was unnecessary to run around town looking for black people to tar or kill, who considered them just like everyone else. They hated them even more than black people. In Port Arthur, they weren't treated badly, as long as they didn't try to go near a school, a bar, or a store." (from an interview with D. Joplin, 1968).

And since Port Arthur had the only school at the time, being rejected there meant becoming a "town pariah."

"She mostly talked to herself." She had a hard time at school. She stubbornly tried to stand out with her clothes and behavior, and for this she was deeply disliked there. There was no one with whom she could find anything in common, or talk about anything. She was one of the first representatives of the revolutionary youth in Port Arthur, of which there are many now" (from an interview with Seth Joplin in the International Times, 1972).

"She was always breaking the rules and causing trouble. We laughed at her simplicity, but tried to stay away from her, although spending time with her was fun. I don't know, frankly, why we started making fun of her" (from an interview with Jim Lyons, a classmate of D. Joplin).

But gradually, Janis began making friends outside of school: she joined a semi-underground group of young people interested in new literature, Beat Generation poetry, blues and folk music, and radical contemporary art. One of them, football player Grant Lyons, introduced Joplin to the work of bluesman Huddie "Leadbelly" Ledbetter, instilling in her a lifelong love of the blues. Soon, she began singing the blues herself, though secretly.

It is generally believed that Janis's psychological problems began in adolescence, and were primarily related to her excess weight. It was during these years that her explosive personality was formed—under the influence of blues singers (Bessie Smith, Big Mama Thornton, Odetta), beat poets, and also her interactions with the most daring Texas guys, who considered her "one of their own."

Janis first sang in Louisiana, where clubs abounded, astonishing audiences with her perfect imitation of Odetta's vocal style. Occasionally appearing on stage at various clubs, she quickly acquired the skills of a professional blues performer. Joplin didn't read music, but she possessed a unique sensitivity that allowed her to absorb the rhythms and emotional spectrum of the blues. It was the hard-edged Louisiana blues that sparked her interest in the philosophy of the Beats. By the time she graduated from high school in 1960, Janis possessed a sound knowledge of music and a desire to develop it further.

In 1960, Joplin enrolled at Lamar University (LU) in Beaumont, Texas. However, her time there was short-lived – she struggled with her classmates, and even there she was considered an outcast.

On December 31, 1961, Joplin made her stage debut at the local club Halfway House, and by January 1962, she was seen (and heard!) on stage at the Purple Onion in Houston, Texas.

From then on, Janis began performing regularly on the university stage, showcasing her three-octave vocal range. Her first recorded song was the blues "What Good Can Drinking Do," in the style of Bessie Smith.

"Janis was influenced by the vaudeville blues of the 1920s and identified with its stars. It was this kind of hyper-expressive soul-blues that allowed her to hear her own inner voice, to understand the depths of her soul" (Lucy O'Brien, rock critic for New Musical Express/NME).

In the summer of 1962, Joplin made her first official visit to Vinton, Louisiana, where, unlike Texas, the drinking age was 18, and the clubs played rock 'n' roll and blues, not the ubiquitous country music.

In July of that year, Janis enrolled at another university—the University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, Texas). Within a month, the local press was writing about her.

"She goes barefoot whenever she pleases, wears Levi's to class because it's more comfortable, and carries a zither with her everywhere in case she feels like singing—it comes in handy then. Her name is Janis Joplin" ("She dares to be different," The Daily Texan, college newspaper, July 27, 1962).

That summer, Joplin and her friend Jack Smith settled in Austin in the "Ghetto"—an apartment squat commune for beatniks and folkers—folk music lovers.

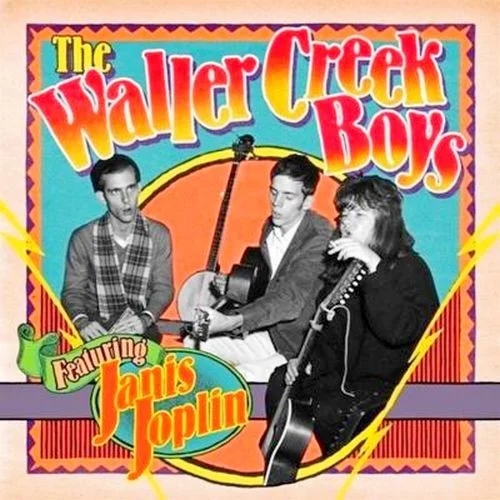

In the fall, Janis joined the folk group the Waller Creek Boys, where, along with Lanny Wiggins (guitar, vocals) and Powell St. John (vocals, harmonica), she began performing on Sundays at the local trade union hall and at the "Bar & Grill," performing songs by Leadbelly, Bessie Smith, J. Ritchie, Rosie Maddox, and bluegrass standards (a blend of country, blues, and jazz). At the same time, the singer became seriously addicted to heavy drinking, pot, and barbiturates.

It is believed that it was then, under the influence of alcohol and smoking, that Joplin's voice acquired the hoarseness that would later make her famous.

"...Janis possessed two completely different voices simultaneously: a clear, bright soprano and a powerful bluesy rasp. For a moment she hesitated, unsure which to choose, and then chose the second" (L. O'Brien).

In January 1963, Janis broke with the student community after one of the college newspapers "jokingly" dubbed her "the ugliest of the bunch." Just then, her old Austin friend Chet Helms, returning from San Francisco, California, reported on the local beatnik scene.

Janis Joplin and Chet Helms.

And on January 23, 1963, the two of them hitchhiked off campus, and just two days later, Joplin performed on stage at San Francisco's North Beach coffee shop, after which, hat in hand, she collected change from the tables "for beer." Coffee Confusion and Coffee Gallery then became her regular "concert venues."

At first, Janis sang a cappella, but soon guitarist Jorma Kaukonen (later of Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna) began accompanying her, and they began performing as a duo. According to eyewitnesses, Joplin "was very relaxed on stage and sang deafeningly."

"Chet (Helms) once brought me to the Coffee Gallery to hear her voice. She sang with just an electric guitar, but so loudly that I had to leave the room and listen to her on the sidewalk." (Luria Castell Dickinson, music journalist).

Among the singer's new friends were guitarists David Crosby (future founder of The Byrds), Nick "The Greek" Gravenites, Sam Andrew, as well as Peter Albin (who was playing progressive bluegrass with J.P. Pickens at the time) and James Gurley.

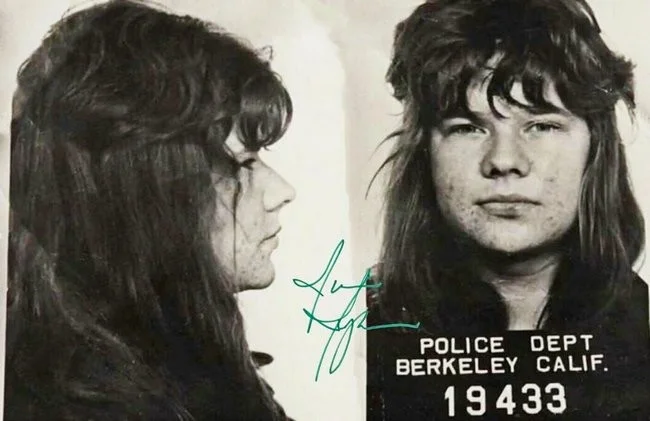

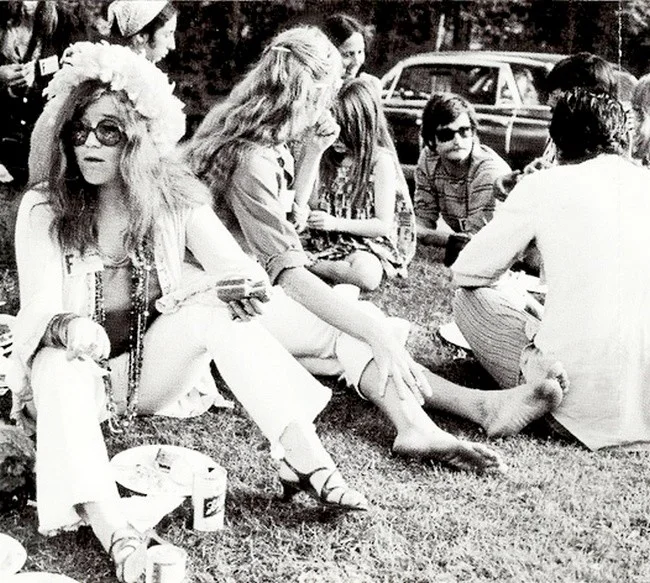

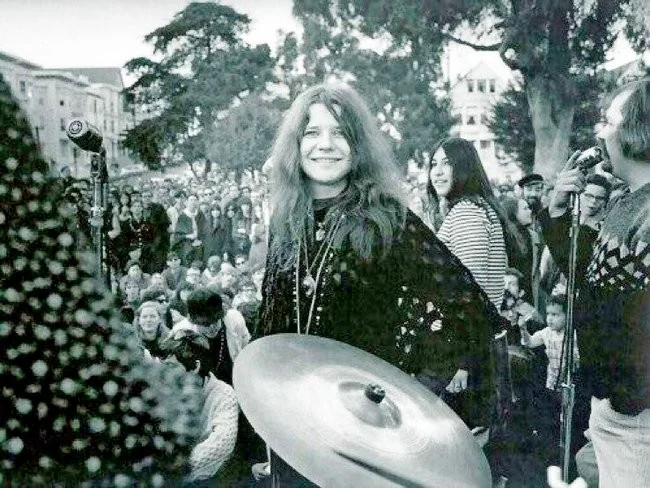

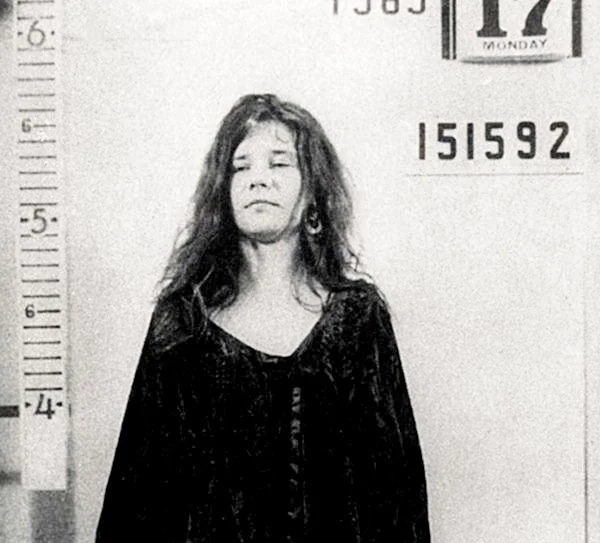

Janis spent half of 1963 working small jobs. In May, she performed with friends at the First Monterey Pop Music Festival (California)—a precursor to Woodstock—after having previously been involved in a motorcycle accident, a street fight, and a stint in jail for petty theft!

A plaque in Berkeley, at the intersection of Shattuck Avenue and Addison Street, commemorating Janis Joplin's arrest here.

"Hippies believe the world can get better. Beatniks know it won't, and they say, 'Screw this world, let's just have a good time'" (J. Joplin).

And in the fall, the singer made her radio debut – live on San Francisco radio station KPFA, performing a blues version of the folk song "Midnight Special" accompanied by Ron "Pigpen" McKernan (harmonica, guitar), the future co-founder of the Grateful Dead.

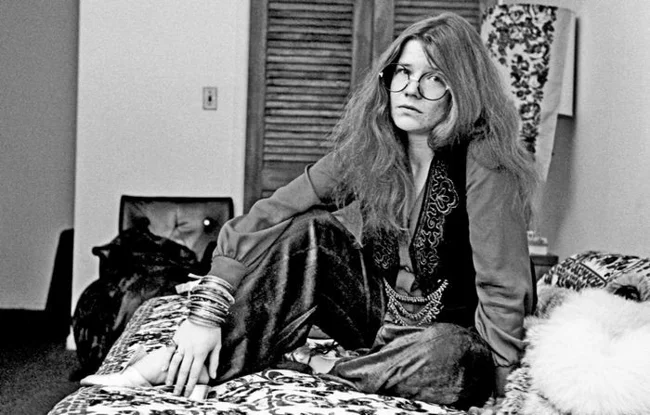

In 1964, Janis settled for a time on New York's East Side, where she dealt with the depression that had developed from various abuses, spending most of her time reading Hesse and Nietzsche and occasionally performing at Slug's, a jazz club in Manhattan.

And on June 25, 1964, returning to San Francisco, she recorded six blues standards with Kaukonen ("Trouble In Mind," "Kansas City Blues," "Hesitation Blues," "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out," "Daddy, Daddy, Daddy," and "Long Black Train Blues"), later released as a bootleg under the title "The Typewriter Tape." The musicians used a typewriter for percussion, with their friend Margarita Kaukonen tapping out the rhythm.

At that time, Janis was already heavily addicted to drugs, which she was using to try to overcome her excess weight and depression. In the spring of 1965, friends, concerned about her emaciated appearance, persuaded Joplin to return to her parents in Port Arthur. Laura recalled that her sister herself was "scared to death" by all these changes. And so Janis returned to her small hometown. She looked frightened and depressed, and never wore short sleeves, lest her mother see the injection marks.

"For the first time in her life, she suddenly began to listen to what her parents were telling her. Janis consulted a psychologist, was determined to continue her education, and generally 'live the life her parents had envisioned for her'" (from L. Joplin's memoirs).

Indeed, in 1965, Joplin returned to college—in Beaumont, Texas, studying sociology at Lamar University (LU), where she spent a year, occasionally traveling to Austin to perform.

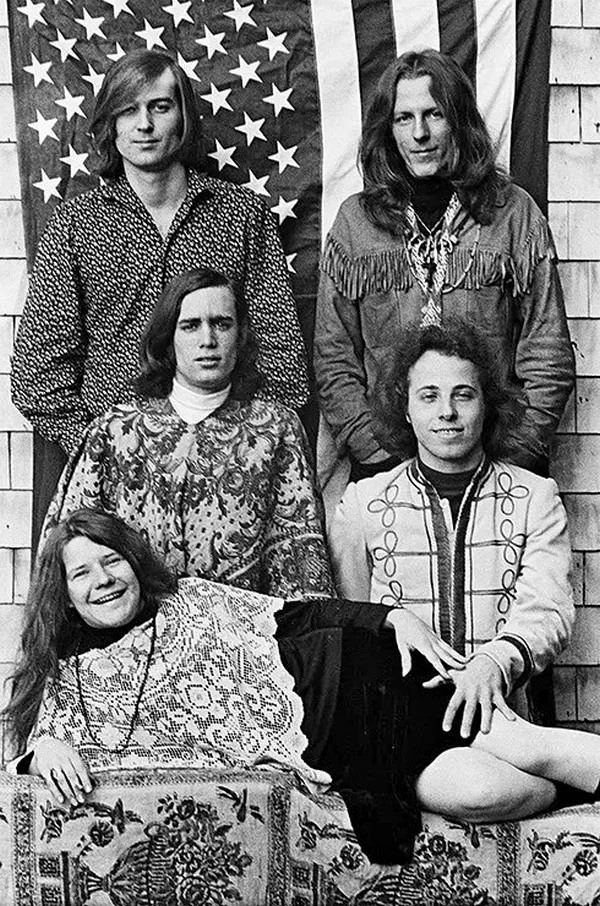

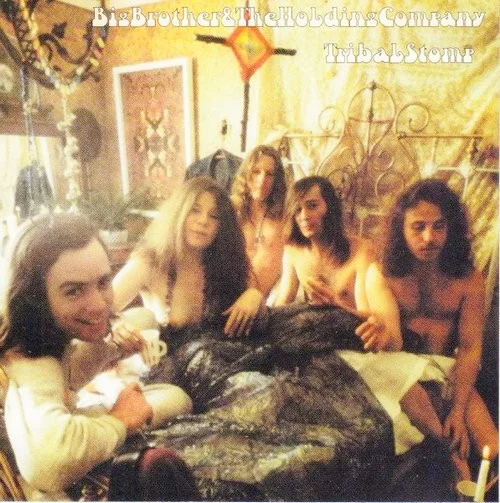

Meanwhile, old friends Albin and Gurley formed the band Big Brother & the Holding Company in San Francisco. A third friend, Helms, signed them and became their manager. It was then that he remembered his old acquaintance Janis and sent their mutual friend Travis Rivers to Texas with the sole purpose of bringing Joplin.

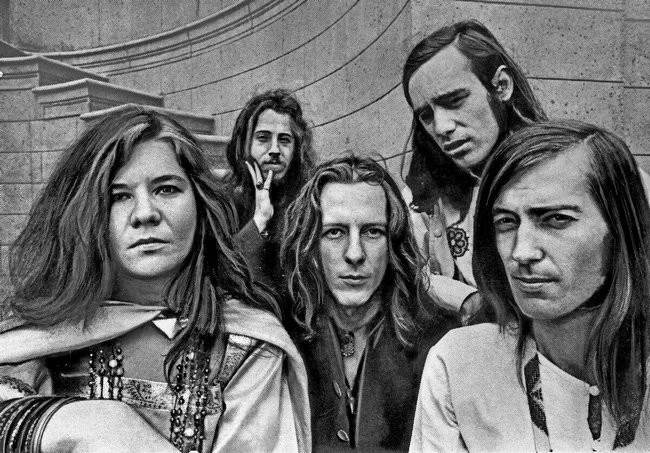

Chet Helms and Big Brother

So on June 4th, the singer arrived in San Francisco. Helms later recalled that "...Peter and Jim waved their hands: 'No, what are you saying, we saw her at the Coffee Gallery, she's crazy!'" Janis, too, had doubts at the time—she had given up drugs and was afraid of relapse. Helms didn't insist, but later suggested that his colleagues try it anyway.

"I did everything I could to convince her that the musicians had cleansed themselves of hard drugs... well, LSD—that's a whole different matter" (from the memoirs of Chet Helms).

And on June 10, 1966, the new lineup debuted at the Abalon Club. Janis sang only two songs, spending most of the concert sitting on a speaker with a tambourine.

"I rented a room: a very nice place, with a kitchen and living room, even an iron and ironing board... Still working with Big Brother & the Holding Co.: it's really interesting... We rehearse every night in the garage of an artist friend of theirs; people come in and listen, and everyone seems to really like my singing... Here are a few more strange names for the collection: The Grateful Dead, The Love, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service... Incredible, right? I'm fine, don't worry. I haven't lost or gained weight, and I'm perfectly fine in my head. I'm thinking about going back to school, so don't count me out just yet!" (from a letter from D. Joplin to her parents, June 1966).

A month later, Janis moved into a mansion in the San Geronimo Valley (Marin County, California) with the musicians, their wives, and girlfriends. She wanted to completely overcome her addictions, and at the urging of keyboardist and close friend Stephen Ryder, she made a pact with her colleague Getz that syringes would be "outlawed" in their apartment.

"...Now my position is ambivalent. The prospect of becoming a second-rate Cher doesn't appeal to me at all. But I'm sure it's a great opportunity, and I won't miss it" (D. Joplin, from a letter to his parents).

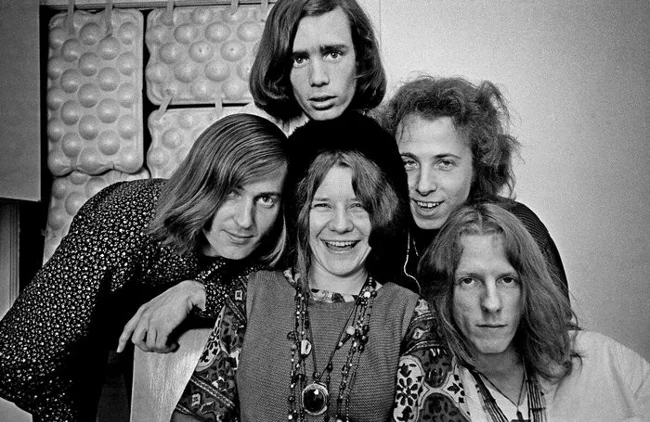

With the arrival of Janis, BB&HC's style changed: the group began playing a synthesis of pop psychedelia and blues, while maintaining its improvisational style. Joplin added new songs to her repertoire: "Women Is Losers" and "Maybe." She and Albin duetted on "Let the Good Times Roll" and "High Heel Sneakers." The band had to turn down the volume—the lead singer's voice couldn't handle the noise.

Thanks to the charisma of their new vocalist, the band became one of the leaders of the San Francisco scene. Lacking any extraordinary musical abilities, the members of BB&HC were "creative people pursuing a path of organic artistic self-exploration" (in the words of S. Andrew).

And the new alliance played a decisive role in Joplin's own creative development—the singer, who had already become accustomed to social rejection, now basked in the rays of universal adoration.

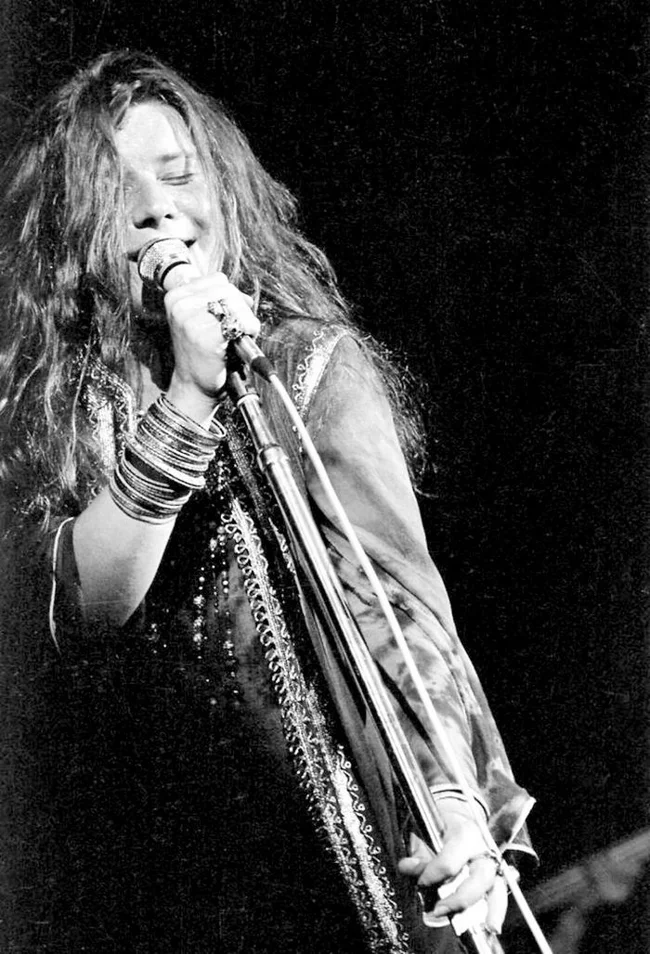

"All my life, I dreamed of being a beatnik, getting hammered, having sex, and having fun: that's all I wanted from life. At the same time, I knew I had a good voice; it would always pay for a couple of beers. And suddenly, it was like someone had thrown me into this rock band. Listen, they threw these musicians at me, the sound came from behind me, a driving bass, and I realized: this is it! – I'd never dreamed of anything else! And it gave me a thrill – purer than with any man. Maybe that was the whole problem…” (from an interview with D. Joplin in the International Times newspaper, London, UK).

And Big Brother also allowed Janis to develop. The musicians didn't force her to sing in any particular style, allowing her to improvise, which was typical of San Francisco bands. But at the same time, the quality of Joplin's vocals changed, and not for the better...

"She started out as an acoustic backing singer, and her voice was rich and folky. In Big Brother, it became less coloratura. At low volumes, Janis demonstrated a fantastic range, but she had to force her vocals to compete with the band's sound. Within a year, she developed polyps, which made every note sound like a chord, complete with semitones" (from the memoirs of P. Albin).

Joplin herself claimed that only after joining the group did she "realize I'd never really sung before."

"I have three voices: a scream, a guttural rasp, and a high howl. When I'm a nightclub singer, I use the rasp. That's what my mother likes. She says, 'Janis, why are you screaming like that? You have such a beautiful voice?'" (from Joplin's memoirs).

She abandoned the practice of copying her former idols, who took over the entire act, because now she had a group behind her.

BB&HC signed with producer Bob Shad's Detroit label Mainstream Records, firing Helms, who objected to the move. But their debut album, recorded later in Monterey, was considered weak by the musicians themselves – the producers only allowed three days for recording, hinting that if they took any creative liberties, they would be fired.

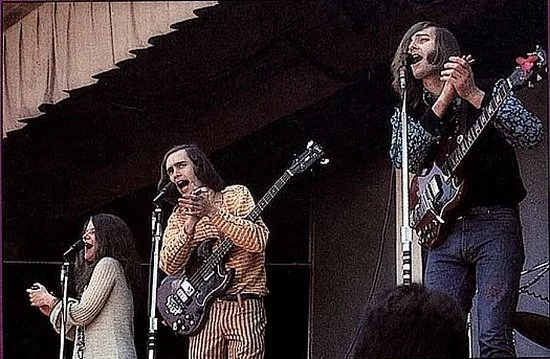

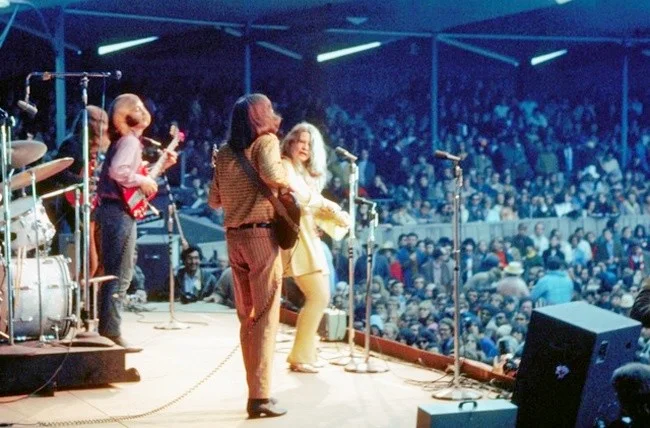

Big Brother & the Holding Company performing in Monterey. From left to right: Janis Joplin, Steve Gurley, Sam Andrew.

In October 1966, their new manager, Julius Karpen, brought the band back to San Francisco, where they played several major concerts, including the Love Pageant Rally in Golden Gate Park, and alongside the Grateful Dead and Orkustra at the New Year's Eve show "Wail/Whale," organized by the notorious Hells Angels motorcycle club to celebrate the release of Chocolate George, one of the gang's members.

On February 10th, in the historic former Golden Sheaf bakery in Berkeley, California, Janis met Joseph "Country Joe" McDonald, the frontman of the local psychedelic rock band Country Joe and the Fish, who later became her close friend. They soon moved in together and rented an apartment.

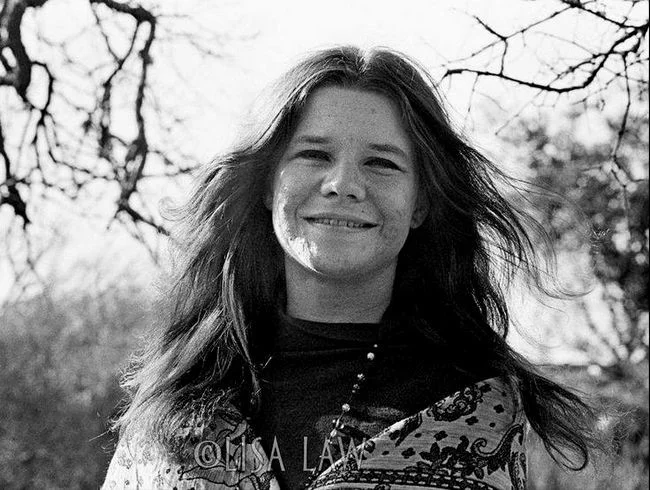

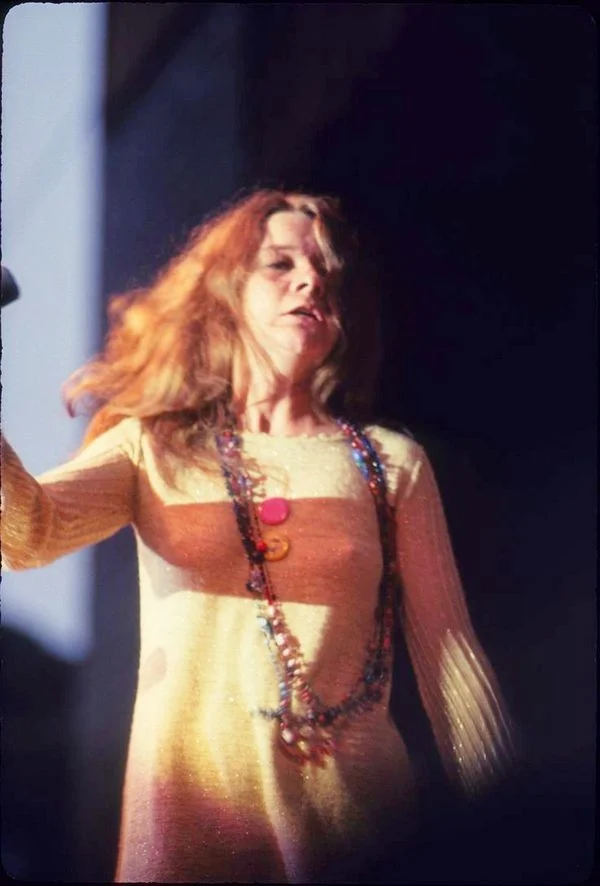

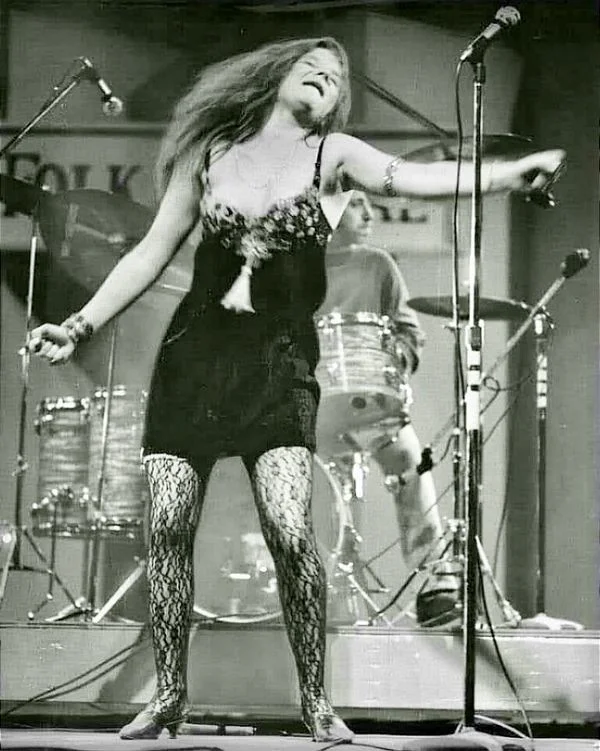

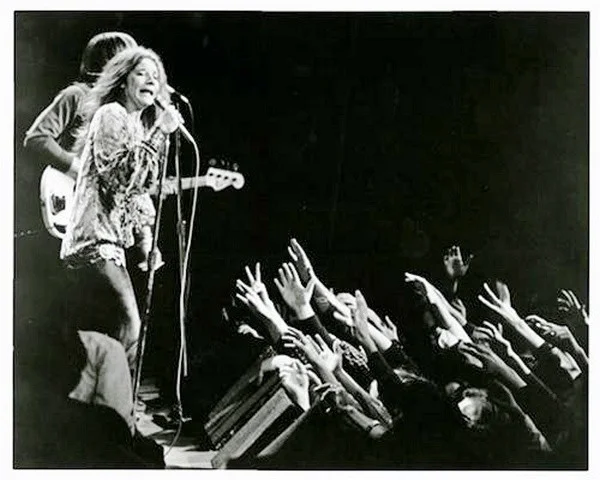

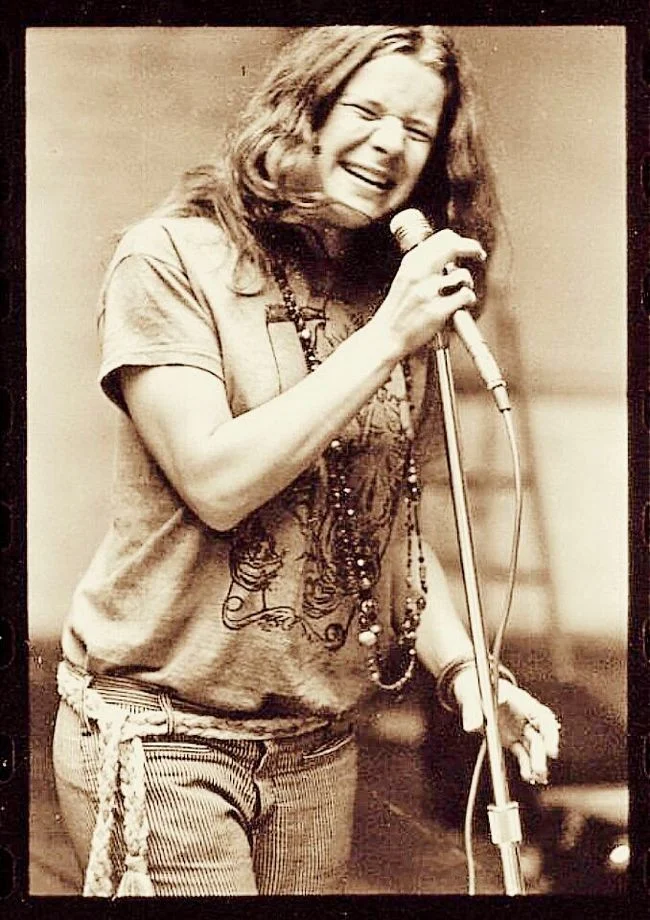

A turning point in Joplin's life was her performance of "Big Brother" on June 17th at the Monterey Festival, and then at a concert specifically organized for filmmaker D.A. Penebaker to capture it. She captivated the audience with her captivating spontaneity and powerful energy, consciously emulating African-American blues performance.

"...Never before had a white singer carried herself like that on stage or used her voice like that" (L. O'Brien).

"I think she sang like a girl who'd come from Texas and been grounded in San Francisco: it was her own voice, her own interpretation of the songs. She sang the blues, and she did it in her own unique way. "Janis was an innovator in a new style, a bearer of gigantic, original, creative talent, and it was impossible to imitate her" (Bill Graham, impresario).

This concert later became the centerpiece of Penebaker's documentary "Monterey Pop."

And on October 31 of that year, Big Brother signed a contract with yet another manager, Albert Grossman, which largely predetermined their future fate. Grossman disdained the musicians, but idolized Joplin, whom he saw as "the new Billie Holiday" and, potentially, the leader of a blues supergroup.

"Whether Joplin sang blues, R&B, or original group compositions (like Getz's 'Harry' or the epic yodel 'Gutra's Garden'), she took everything to emotional extremes with her rough, husky voice... Leaning over the microphone, her fingers clasped, her hair covering her face, she clearly stood out from the 'flower utopia' of the psychedelic scene. "There was a certain fatal intensity in her voice" (J. Sculatti, D. Shay, from the book "San Francisco Nights: The Psychedelic Music Trip 1965-1968," 1985).

Columbia Records president Clive Davis signed BB&HC to a three-album deal and helped Grossman free himself from his old contracts. The new deal was signed after the band's debut album, released on Mainstream Records in the summer of 1967 and reaching number 60 in the US charts.

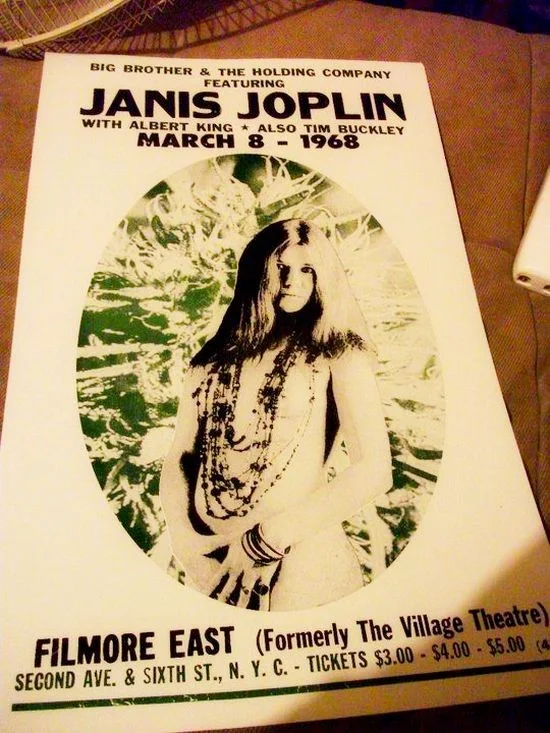

On February 16, 1968, Big Brother began their first East Coast tour, and the next day they performed for the first time at the Anderson Theatre in New York City, a community theater that hosted rock 'n' roll and experimental productions in the 1960s and '70s. The concert received rave reviews.

"Janis isn't exactly a beauty, but she's certainly a sex symbol, albeit in a somewhat unexpected package." "Her voice combined the soul of Bessie Smith, the brilliance of Aretha Franklin, and the drive of James Brown... Soaring to the heavens, this voice knows no bounds, as if giving birth to a divine polyphony within itself" (Village Voice, a news and cultural publication, New York).

Janis wrote to her parents then: "Here it is, the first New York review of our first concert!... Everything points to me becoming rich and famous. Unbelievable! Magazines are vying with me for interviews and photo shoots, and I won't refuse any of them. Wow, I'm so happy! I've been running around like a lost child for so long... and now this has happened. The main thing is, it looks like I'll really succeed this time. Incredible. Well, stick this clipping somewhere so everyone can see. I'm so proud!"

Many reviewers also noted the discrepancy between the lead singer's level and the rest of BB&HC, and that without Joplin and her "thermonuclear" performance, they were worthless.

"There would be no Big Brother & the Holding Company without Janis Joplin... These days, a rock band resembles a beehive: three or four worker bees buzzing around a queen bee" (BMI Magazine, "Bee Rock-Queens," 1968).

In March 1968, the group, now billed as Janis Joplin and Big Brother & the Holding Company, began work on their second album. It was then that tensions arose within the band: the musicians sensed that Joplin was becoming a superstar, while they were becoming her backing band. Janis, more and more, began to hear that the group wasn't living up to her level of performance.

On April 7, BB&HC concluded their tour with a major concert in memory of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) in New York City, which also featured Jimi Hendrix, Buddy Guy, Richie Havens, Paul Butterfield, and Elvin Bishop.

Following this, during the April 12-13 tour, a live album, later titled "Live at Winterland '68," was recorded from the band's performance at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco.

The release of the studio album, however, was delayed, as the producer rejected almost all of the band's proposed material. However, pre-orders for it were so overwhelming that it was certified gold even before its release. Clive Davis demanded an immediate release, and in August 1968, "Cheap Thrills," with cover art by Robert Crumb, a well-known cartoonist in underground circles, was finally released.

In it, the band created "a collection of wild studio and live experiments," fully expressing their power. But the media noted that Joplin's strength lay more in her interpretations of existing material than in her originality. However, she herself was at the height of inspiration and wrote several truly powerful songs. And it was "Turtle Blues" that became a defining moment in her career.

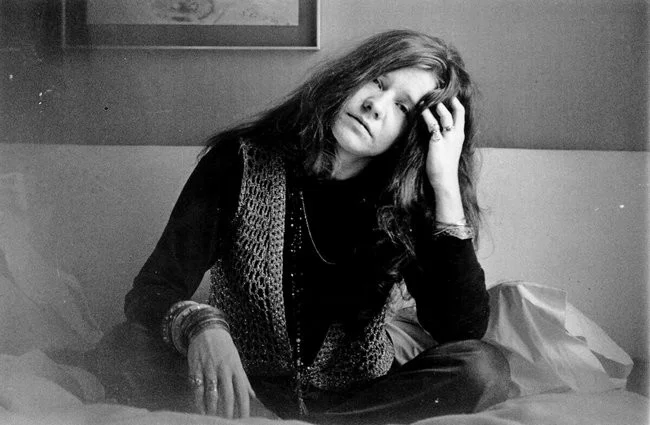

"It's all about feeling. Something that rolls over you, reminiscent of sex, but higher in meaning. Love, passion, warmth—everything that touches us from within and brings such pleasure. Sex is only one component here. I don't think while singing." "I just close my eyes and feel... feel the thrill" (from an interview with Janis Joplin in Newsweek magazine, February 1969).

A month after its release, the album sold a million copies, and on October 12, 1968, it topped the Billboard Hot 100, staying there for eight weeks. However, press reviews were rather lukewarm, with critics unanimously declaring that Janis overshadowed the entire group with her performance, particularly on tracks like "Ball & Chain" and "Summertime."

Despite the album's success, the punishing touring schedule and the resulting stress and petty squabbles took their toll on the band and predetermined its breakup. It became clear that only Joplin could survive the group's breakup and even achieve success as a solo artist.

And in September 1968, Grossman announced the "amicable separation" of Janis and Big Brother. On November 15, she gave her last concert with the old lineup—on the East Coast at Hunter College in Manhattan. Their very last concert together took place on December 1 in San Francisco.

Joplin's decision took no one by surprise: it had been brewing for several months. Andrew left the band with her.

Jenisa was deeply troubled by her departure, but she understood that she needed to move on to further development. They had been working six days a week for two years, playing the same songs over and over again, and had simply exhausted themselves, both physically and musically.

Grossman set about forming a new lineup. He enlisted the help of guitarist Mike Bloomfield (ex-Electric Flag) and the already familiar Grek-Grevinaitis. And on December 18, 1968, the musicians gathered for rehearsal. The new band also included Terry Clements (saxophone), Terry Hensley (trumpet), Richard Kermode (organ), Roy Markowitz (drums), and bassist Keith Cherry, who was later replaced by Brad Campbell (ex-The Paupers). From many possible names, they chose the Kozmic Blues Band.

The still-poorly formed band's first performance took place on December 21st at the Yuletide Thing Christmas show at the Mid-South Coliseum in Memphis, Tennessee, alongside several professional soul bands.

Kozmic Blues Band

The musicians were received rather coolly. Rolling Stone magazine published a nearly scathing article in its report on the program. The San Francisco Chronicle, however, directly offered Janis a return to Big Brother, "...if they're willing to have her."

KBB suddenly found success following their European tour. After concerts in Frankfurt (West Germany), Stockholm, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Paris, the band performed at London's Royal Albert Hall on April 21, 1969, receiving rave reviews from the British press (Melody Maker, Daily Telegraph, and others). NME magazine called Joplin's British debut "triumphant."

The singer herself believed she had "broken through the wall" of traditional British reserve, which she considered unshakable.

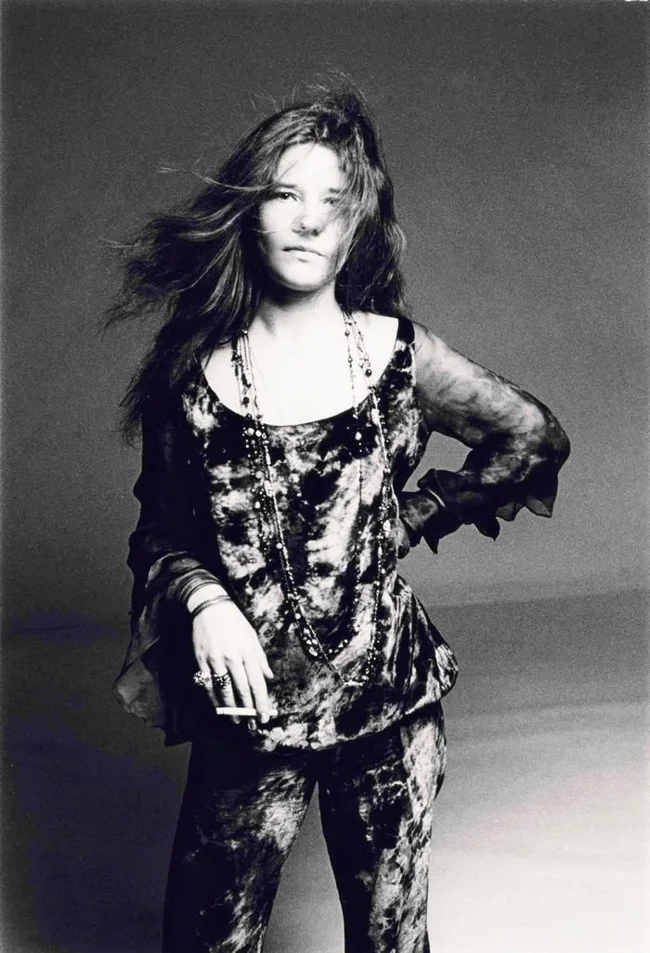

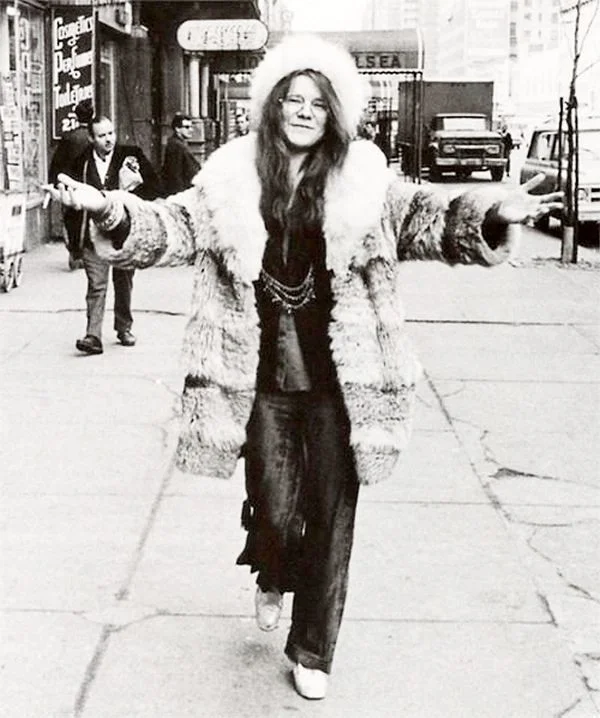

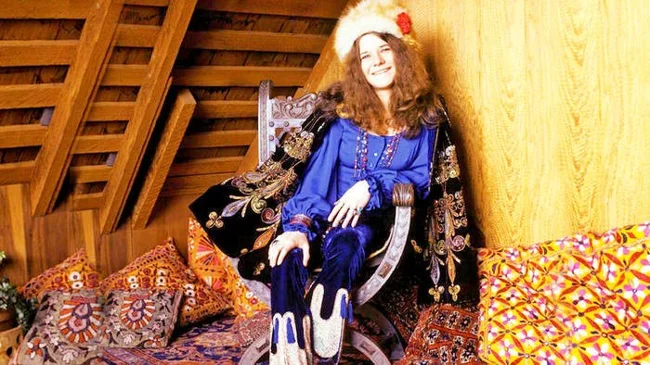

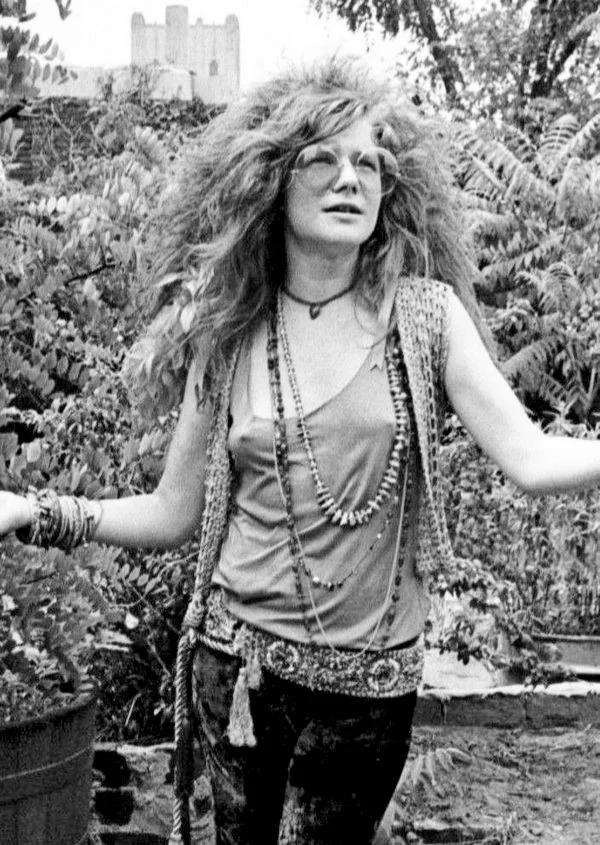

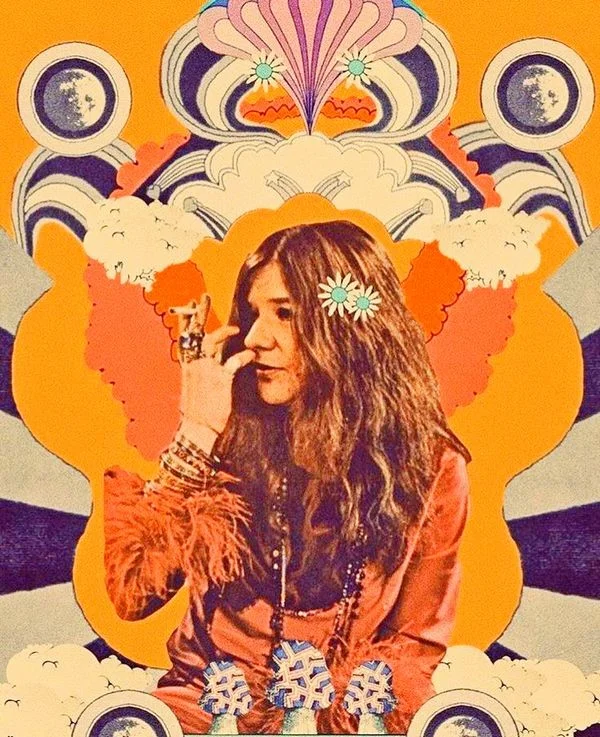

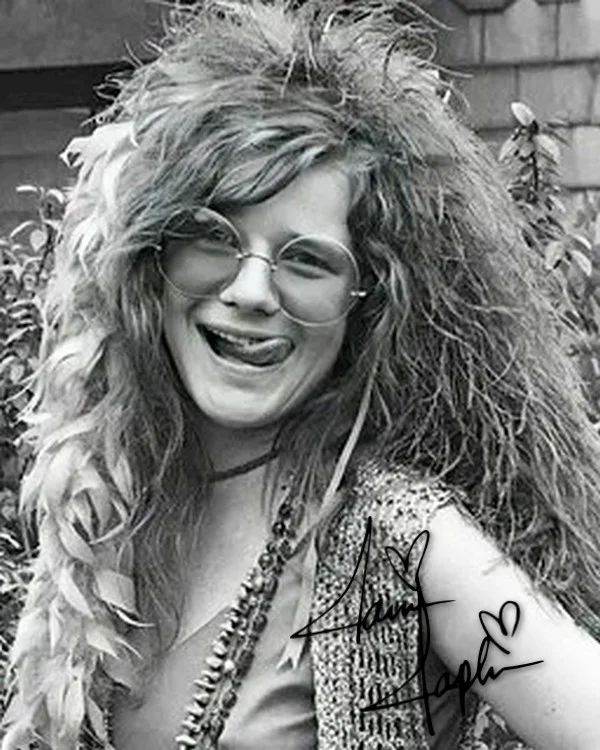

And Janis experiments with style, performing at concerts and giving interviews. She shocks everyone with her behavior and outfits, but now it's her signature look. No one considers her ugly anymore. And famous photographers shoot her for magazine covers, print her on posters and T-shirts. The singer is becoming a style icon, and even a symbol of feminism.

But her new band has generally disappointed both experts and fans. According to Andrew, the problem was that Big Brother was a group of like-minded individuals living as a family, while KBB was largely just Janis's backing band, recruited from "hired hands."

"While individually the Kozmic Blues Band musicians were stronger than the Big Brother members, they couldn't even come close to the latter's creative power. The former were professional nightclub musicians, the latter were artists and performers... There were moments, especially on tour in Europe, when we had a good time, but mostly there was complete confusion; no one understood anything: neither Janis nor the band" (from S. Andrew's memoirs).

"The potential for a truly great rock singer is certainly evident. But so is the infamous and downright deadly tendency toward vocal excess. Janis doesn't so much sing a song as strangle it to death in front of everyone. The spectacle is exciting, but unpleasant. It has far more to do with carnival exhibitionism than with musical art." (Paul Nelson, Rolling Stone, March 15, 1969).

In June 1969, KBB began working on an album at Hollywood Studios with producer Gabriel Meckler, known for his work with Steppenwolf.

While still working in the studio, the band played a concert in June 1969 at the Newport Pop Festiva in Northridge, California, and at the first Atlanta International Pop Festival, held in July at the Atlanta Speedway in Hampton, Georgia.

On August 16, 1969, Janis and the Kozmic Blues Band performed at the now legendary Woodstock Music & Art Fair, playing a 10-song set, including the hits "Summertime" and "Ball and Chain" (later released on the album "Woodstock Experience"). However, before heading to Woodstock, Sam left the band, and guitarist John Till went to the festival in his place.

Rumor has it that Joplin "fired" Andrew for stealing her drugs. He also claimed that the split was due to their failure to write songs together, which is why they left BB&HC and formed a new band. However, he didn't deny the influence of drugs on his relationship with Janis.

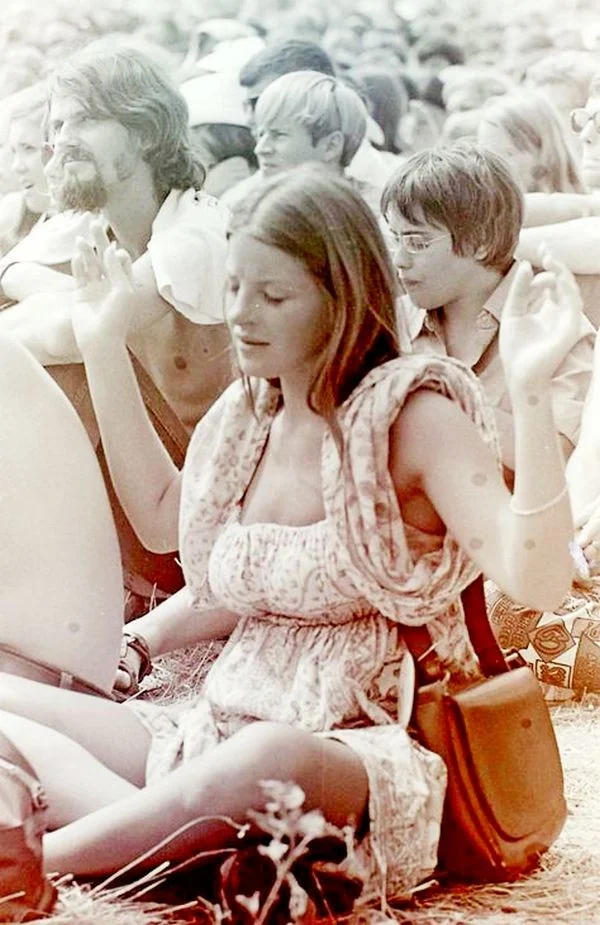

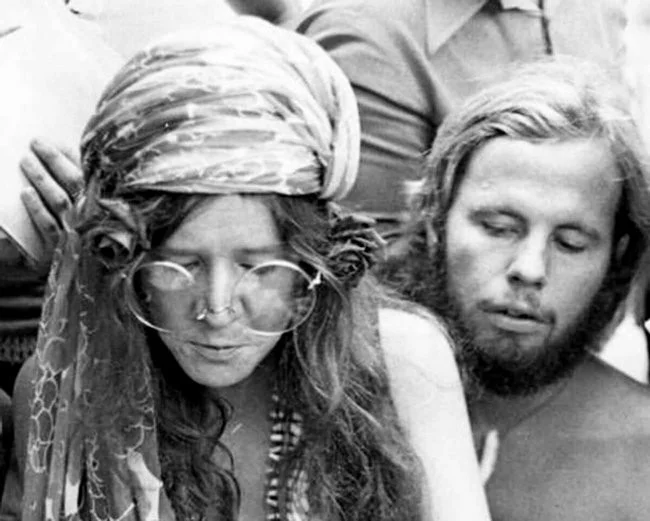

Woodstock

And at some point, a girl named Peggy Casserta begins to appear next to her. The producers and all the members of KBB hate her—Peggy always carries enough drugs in her purse to keep her out of life for a week, and Janis is literally glued to Peggy and her "magic purse."

Janis Joplin and Peggy Casserta

But the album "I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama!", released in October 1969, reached number 5 on the Billboard 200 and soon went gold, although it was met with a lukewarm reception from the American press. European media, on the other hand, reacted almost enthusiastically. Many noted that in places the album's material fell short of Joplin's level, while in others she elevated it to her own level.

But Janis, though a brilliant singer, failed to establish herself as a leader. She couldn't control herself or direct the musicians, coordinating their performances. At the same time, she couldn't stand the fact that others were trying to do this for her. Bloomfield and the Gravenites, meanwhile, relegated Joplin to the background, a position she wasn't accustomed to.

On November 27, 1969, Joplin and KBB performed with Tina Turner and the Rolling Stones at Madison Square Garden in New York City. The December 19 concert, which also featured Johnny Winter and Paul Butterfield, was hailed by the press as "a showcase of blues-rock at its finest." However, the December 21 Madison concert proved to be KBB's last; the group disbanded in January 1970.

With Tina Turner

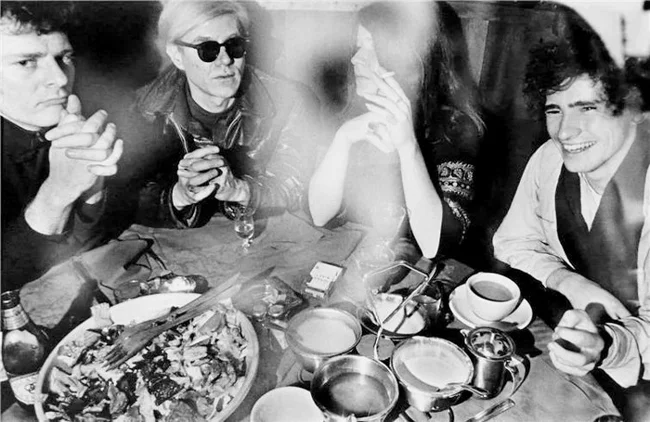

Joplin, Warhol, and the Rolling Stones

But already in March 1970, Joplin, now without her band, recorded the track "One Night Stand" with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and producer Todd Rundgren at Columbia Studios in Los Angeles. It wasn't released until 1982.

In April 1970, Janis temporarily returned to BB&HC and performed with the group at the historic rock 'n' roll venue, the Fillmore West, in San Francisco. A week later, they performed together again in Winterland, Newfoundland, Canada. Highlights of these concerts were later included on the compilation album "Joplin In Concert" (1972).

Then her old passions returned, and the singer decided to escape to Brazil and lose herself in the colors of carnival. In early spring, Joplin visited Brazil and El Salvador, where she managed to perform with local musicians.

Janis Joplin at the Rio Carnival. 1970

On Ipanema Beach, she met a guy who seemed perfectly suited to the role of savior. Writer and artist, beatnik, and globetrotting musician David Niehaus. Joplin traveled with him for a couple of months through Latin America.

"For three evenings, my friends and I went to this big brothel of theirs: a quartet was playing, and I sang with them" (from Joplin's interview with Rolling Stone magazine, 1970).

Janis Joplin and David Niehaus

In March 1970, the rested singer formed a new group, the Full Tilt Boogie Band, featuring Canadian musicians led by guitarist John Till, whom she had met while touring with BB&HC. The group rehearsed for its first time in April.

Janis was full of enthusiasm. She loved everything about it: the elimination of the horn section, the lack of rush—they just played without worrying about the concert schedule—and the new sound, which she herself called "down-to-earth blues" or "loud electric funk-country blues."

In May 1970, FTBB played their first concert—on the same bill with Big Brother and their new frontman, Gravenites, in San Rafael, California. They then toured Canada with The Band and The Grateful Dead. However, financial problems forced the tour to be suspended. Meanwhile, David, without saying a word, flew off to Africa.

On July 8, 1970, Joplin performed at the Honolulu International Center Arena, an arena inside the Neal S. Blaisdell Center in Honolulu, Hawaii, where 7,000 spectators gave her a standing ovation.

In September of that year, Janis and FTBB began working on the album in Los Angeles, inviting producer Paul A. Rothchild, known for his work with The Doors. He accepted the invitation with hesitation, but soon became delighted with his new protégé:

"After the mess with the Kozmic Blues Band, which, in my opinion, almost ruined her career, I talked to Janis, made sure she was really healthy, and agreed to accompany the band on tour to see what she looked like on stage. Janis was magnificent."

The band began work at Sunset Sound Studios, where Rothchild had recently recorded two albums for The Doors. Joplin attended every session, was deeply involved in the work, and clearly enjoyed it.

"Never had I seen her so happy as during these sessions. She was at the peak of her form and enjoying life. Again and again she talked about how good she was in the studio. After all, until then, she had associated the recording process only with friction and quarrels" (from the memoirs of P. Rothschild).

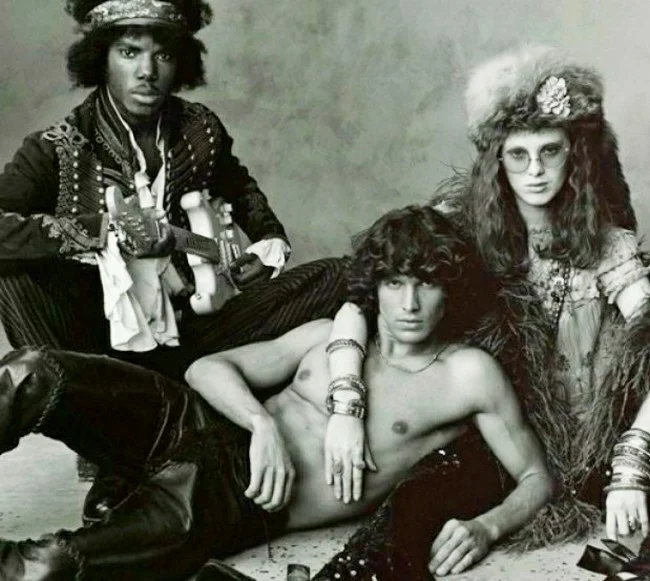

Rothschild also dreamed of introducing Janis to his former "mentee," Jim Morrison, and even brought them together "accidentally" at a party in Hidden Hills. All three arrived sober. Things started off well. It was clear that Joplin and Morrison were attracted to each other. But while alcohol had a calming effect on Joplin, making her "utterly charming," a drunken Jim became rude and insolent. As a result, Janis punched him in the face when he tried to "get closer," something he later recalled with a smile.

On October 3, while working in the studio, the singer listened to an instrumental version of the album's final track, Gravenites's "Buried Alive In The Blues," whose vocals were scheduled to be recorded the following day.

But on the morning of October 4, 1970, Joplin showed up at the studio. After she failed to answer several phone calls, Rothschild sent one of his assistants to room 105 of the Landmark Motor Hotel on Franklin Avenue, where the singer was staying. When attempts to knock on the door were unsuccessful, a hotel clerk was summoned with a key. When the door was opened, Janice was found lying face down in her nightgown on the floor between the bed and the nightstand. When they turned her body over, her nose and lips were bloodied. She was clutching a $4.50 bill in her fist.

Despite the fact that a large quantity of opiates was found in Joplin's system during her autopsy, no illegal substances were found during the initial search of the room. Moreover, it seemed odd that the police, when they arrived, found the room so clean and tidy, with no signs of disorder. This led to suspicions that someone unknown to Janice, who was in her room, had destroyed all the evidence and fled.

Another oddity was that, according to the medical examiner, death occurred less than 10 minutes after the injection. This could have happened if Joplin had injected the drug subcutaneously, but everyone knows she never did this, seeking a faster reaction. All these circumstances gave rise to numerous rumors of possible murder.

Suicide was also discussed for some time. Consequently, the insurance company refused to pay the family. Gradually, it became clear that this theory had only one active supporter—Grek. Andrew, however, considered it implausible; according to him, Janis was very pleased with the progress of the album recording and got along well with the musicians. He believed that Joplin "most likely simply received exceptionally strong, purified heroin... after all, it's known that there were several fatal overdoses in Los Angeles that weekend."

Sister Laura shared this view, claiming that the dealer from whom Janis regularly purchased her heroin always tested the product beforehand with a local pharmacist. But the expert wasn't present that evening, and Joplin received a dose almost 10 times stronger than usual.

"I consider her death a terrible mistake. She wasn't depressed or frustrated. She was making plans and looking to the future with hope. She even finally got her hair done!" (L. Joplin).

As Newsweek magazine later noted, Joplin's death was a cruel joke of fate, as it occurred just when the singer's life was just beginning to improve: she had been drug-free for almost six months, was working hard, and was even planning to marry her friend Seth Morgan.

However, Joplin's newfound prosperity was illusory; she still felt lonely (on the night of her death, her "fiancé," Morgan, was partying hard in the pool room of a strip club).

Although her biographer Myra Friedman believes that the word "accident" should be understood only in its most general sense, and that it was an "unintentional suicide."

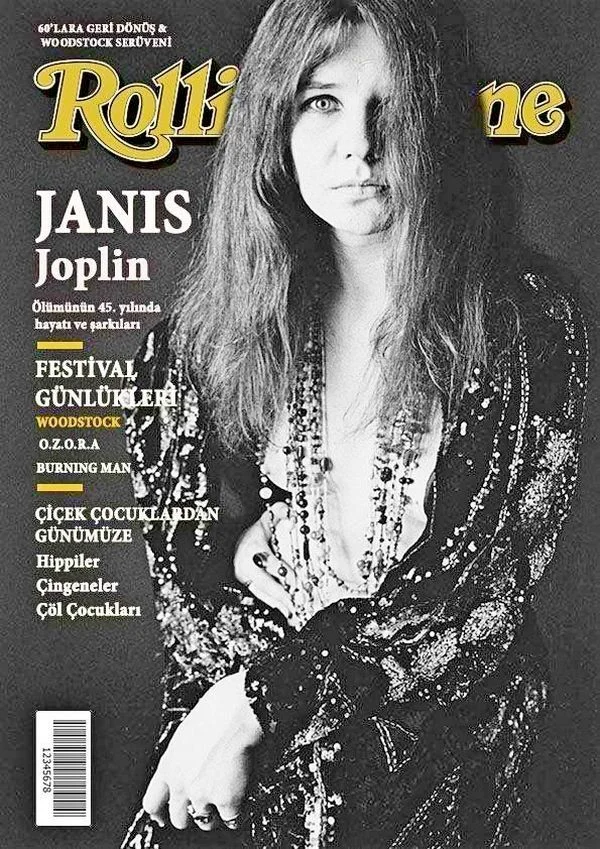

Immediately after Joplin's death, Rolling Stone magazine dedicated a special issue to her memory.

"She chose the perfect time to die." There are people who can only live on the rise, and Janis was just such a rocket girl... If you assume a person has the ability to write the script of her life, then I would say she wrote a good script, with the right ending" (from an interview with Jerry Garcia, guitarist of the Grateful Dead, in Rolling Stone magazine, 1970).

"Janis Joplin restored an old symbol to a new generation, becoming the definitive embodiment of our sense of tragedy; a concept by which we can measure the level of pain. We cast her in the role of the archetypal loser, and she filled it willingly and perfectly. She never disappointed us—either in the tragedy of her death or in the ironic brilliance of her last album, called 'Pearl'—a nickname by which some close to her knew her. But for me, the album's title suggests a different meaning. A constant, painful irritation is what produces the pearl, this disease of the oyster. Gustave Flaubert said that the artist is the disease of society. Janis was the disease of the gigantic American loneliness. She is a true pearl" (J. Marks, reviewer for the New York Times, 1971).

Janis's remains were cremated at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Westwood Village, California, and her ashes were scattered in the Pacific Ocean along the California coast.

The singer's final recordings were "Mercedes Benz" and an audio birthday greeting to John Lennon, dated October 1, 1970, which was delivered to the Beatle in New York after her death.

The news of Joplin's death was a terrible blow to everyone involved in the new album's production, as it was almost complete. Rothschild debated whether to complete the work himself or release the unfinished album as is. Ultimately, he decided to finish the album, dedicating it to the singer's memory. Gravenites' song "Buried Alive in the Blues," for which Janis hadn't recorded vocals, was included as an instrumental.

Released in February 1971, Pearl is considered by many to be Joplin's most balanced and organic work, reflecting her increased vocal prowess and her lingering emotionality, combined with polished arrangements.

"Pearl is not just her best album, but the best album ever recorded by a white female blues artist" (William Bender, reviewer for Time magazine).

On February 27, 1971, "Pearl" topped the Billboard 200 and stayed at the top for nine weeks. "Mercedes Benz," which the singer co-wrote with beat poet Michael McClure, and an acoustic version of "Me and Bobby McGee" were later included on the compilation album "Janis."

A member of Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Kozmic Blues Band, and the Full Tilt Boogie Band, the singer, who released only four studio albums (one of which was posthumous), is considered the finest white blues singer.

They say Joplin never forgot her teenage problems, forever mired in that atmosphere. Or maybe she simply didn't want to grow up?

Among the posthumous music releases, the soundtrack to the film "Janis" (1975) was particularly notable, featuring recordings of the singer's performances from 1963-64. Allmusic, on the other hand, gave the release a low rating, noting that two key tracks, "Piece of My Heart" and "Cry Baby," featured in the film were omitted to accommodate archivists. The film, directed by Howard Elk and released a year earlier, included Joplin's 1970 performances on Dick Calvert's television program, her 1969 concert at Woodstock, a 1967 television segment, and footage of her 1969 European tour.

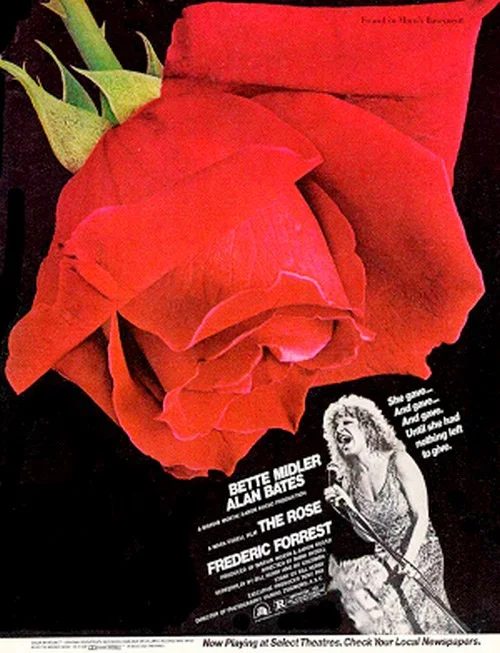

In 1979, the film "The Rose" was released, telling the story of a rock singer who leads a self-destructive lifestyle, unable to cope with the demands of her career and the dictates of a ruthless manager. The original film was based on the life and work of Joplin. Bette Midler played the lead role and was nominated for an Oscar for Best Actress.

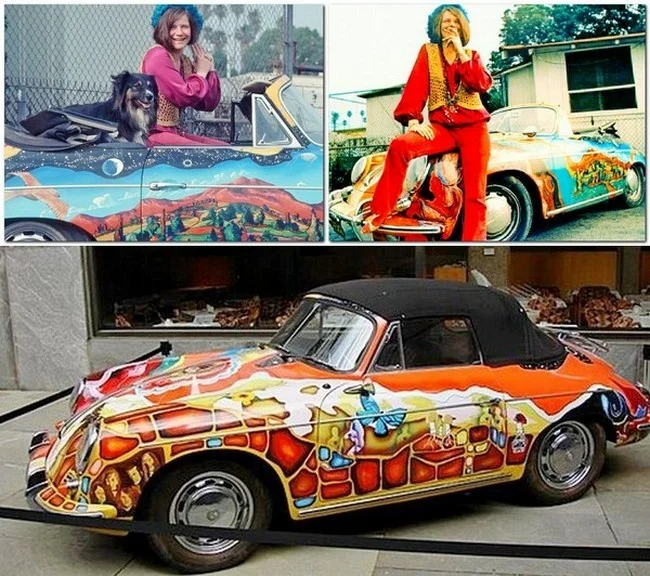

In 1991, an oil on canvas painting by 13-year-old Janis Lyn Joplin, "Jesus in Gethsemane," was discovered in a Port Arthur Sunday school. It was exhibited at the Gulf Coast Museum. In November 1991, a collection of 300 items related to Joplin was included in an exhibition that opened at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum. The opening ceremony was attended by members of BB&HC: Getz, Andrew, Gurley, and Albin. Among the exhibits at the Hall of Fame Museum was her Porsche 356, painted in a psychedelic art style.

Janis Joplin's Porsche 356 on display at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

In 1995, Joplin was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, "for outstanding achievement."

Janis Joplin ranks 46th on Rolling Stone magazine's list of "The 50 Greatest Artists of All Time" (2004) and 28th on the same magazine's list of "The 100 Greatest Singers of All Time."

In 1992, Laura Joplin published a biography of her sister, "Love, Janis" (Villard), based largely on letters Joplin wrote to her and her mother. In it, "Janis the humble small-town girl and Janis the superstar seemed to be depicted on opposite sides of the same coin."

In the late 1990s, with Sam Andrew as musical director, the book was adapted into a musical that enjoyed a successful run on Broadway. Many renowned performers, including Laura Branigan and Beth Hart, starred in the title role.

In 2009, Janis's work became the basis for the "American Music Master" series of themed concerts and lectures held annually at the Hall of Fame.

In 2007, Penelope Spheeris began work on the biopic Gospel According to Janis (2010), starring Zooey Deschanel.

In 2015, the documentary Janis: Little Girl Blue, directed by Amy D. Berg, was released. It is based on Joplin's letters, narrated by indie rock connoisseur Charlene Marshall, better known as Kat Power, as well as excerpts from Janis's performances and interviews. The film was screened as part of the documentary section of the 40th Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF).

Laura Joplin on stage at the American Masters program during the Television Critics Association press tour for her book "Janis Is a Little Girl Blues," 2016.

In 2013, the singer received a memorial star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

"Janis is not a victim of society or a prophetic figure; "She's an immature child who failed to discipline herself—to the point that she simply couldn't survive" (Midge Decter, journalist).

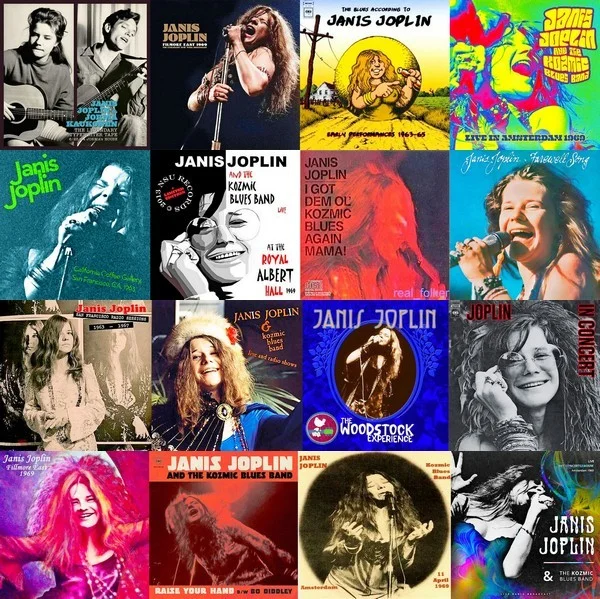

Joplin's Discography:

Studio Albums:

Janis Joplin & Jorma Kaukonen: "The Typewriter Tape" (1964);

Big Brother and the Holding Company: "Big Brother & the Holding Company" (1967), "Cheap Thrills" (1968), "Live at Winterland '68" (1998);

Kozmic Blues Band: “I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues.” Again Mama! (1969);

Full Tilt Boogie Band: "Pearl" (posthumously, 1971);

Big Brother/Full Tilt Boogie Band: "In Concert" (1972).

Singles: "Kozmic Blues" (1969), "Me And Bobby McGee"/"Half Moon" (1970), "Cry Baby"/"Mercedes Benz" (1971), "Get It While You Can"/"Move Over" (1971), "Mercedes Benz" (2003).

Compilations: "Janis Joplin's Greatest Hits" (1972), "Janis" (1975, double album), "Anthology" (1980), "Farewell Song" (1982), "Cheaper Thrills" (1984), "Janis" (1993), "18 Essential Songs" (1995), "The Collection" (1995), "Live at Woodstock: August 19, 1969" (1999), "Box of Pearls" (1999), "Super Hits" (2000)

Films about Joplin: The Rose (dir. Bill Rydell, 1979), Janis Joplin: Southern Discomfort (BBC, 2000), Janis: Little Girl Blue (dir. E. Berg, 2015)

Add your comment

You might be interested in: