Atacama Desert: Only space is drier (13 photos)

A place where the earth hasn't seen a millimeter of precipitation for 400 years, the coldest desert on the planet and simultaneously the highest, where tourists often forgo sightseeing due to frequent bouts of altitude sickness. Plus, there are Martian landscapes, deep blue lagoons, flamingos poking their beaks in the water, llamas, vicuñas, guanacos, geysers, thermal springs. And the world's largest telescopes.

This is a complete mess, completely unsuitable for the title of the driest or coldest desert on the planet. Are these "most" titles invented for tourist appeal and catchy headlines? Let's figure it out.

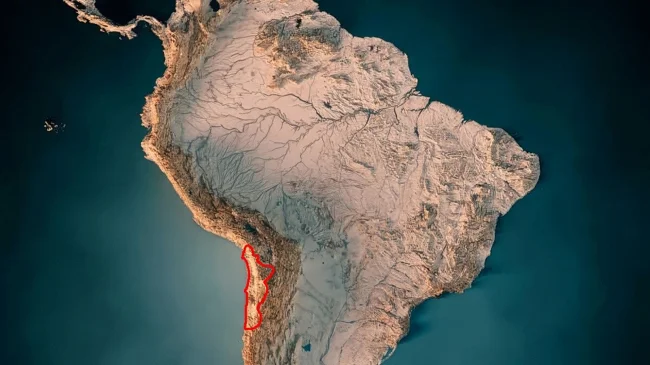

Atacama Desert in Chile

In the Vestiges of Two Mountain Ranges

Every educated person knows that a desert isn't always sand. They also know that the largest desert in the world isn't the Sahara (it's only third), but the Antarctic, which occupies the entire icy continent. It's also the coldest, so the Atacama "title" alone is no longer credible. The same applies to the second, as the Great Antarctic Desert is also the driest place on Earth—its snow-free stretches haven't seen precipitation for a couple of million years, if not longer. So, the Tibetan Plateau has taken the title of the planet's highest desert from the Atacama, as it sits at an altitude of 4,500 meters, while the average elevation of the Atacama is only 2,300 meters. So, is this a lie? Not quite. The Atacama is the driest and coldest non-polar desert on Earth. That would be a more accurate way to describe it. But then how can the driest desert have geysers, lagoons, and a rich wildlife? Here's the thing. The Atacama's area is comparable to that of Bulgaria. One edge touches the Andes, the other faces the Pacific coast. In the south, its borders merge into a valley constantly flooded by rain. Of course, with such a diverse landscape, the Atacama could support a quite comfortable life.

Atacama on the map of South America

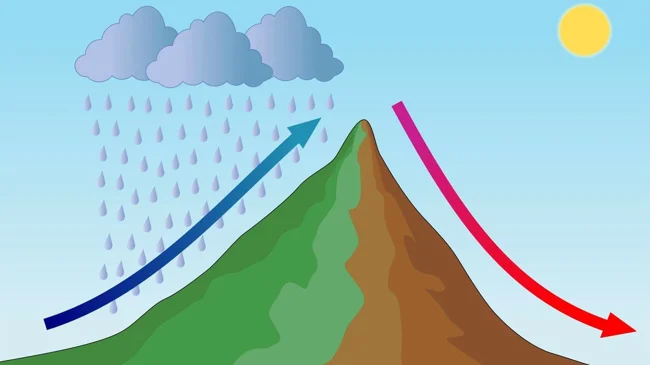

But it also has dry spots, and indeed, throughout the entire history of meteorological observations (which is about 400 years), it has never rained. Therefore, the desert's center is extremely sparse, and the terrain resembles lunar craters or the reddish dunes of Mars. The lack of moisture is due to the Atacama's unique topography. We all know that Chile is a country stretching along the Pacific Ocean, with the Andes forming its eastern border. And on the other side of the mountains are the Amazon rainforests, fed by rivers flowing down from the mountains. But the clouds that form there cannot overcome the mountain peaks, so they pour down as rain on the eastern slopes of the Andes and arrive on the other side as dry and heated air.

Air movement pattern in the Andes

But isn't the Pacific Ocean lapping to the west of the Atacama? Surely it should moisten the coastal region? It should, but there, in the path of the moist air, stands a mountain range called the Coastal Cordillera, and the rain clouds also pour down on the slopes, unable to overcome the peaks. The Atacama's geographic location is precisely between these two mountain ranges, cutting it off from the moist air to the west and east. Of course, this isn't all of the Atacama, just its nominal center—lifeless and dry as space itself. The rest of the territory is a vibrant landscape of vegetation and wild animals unafraid of humans. In fact, it's not quite a desert, but rather a semi-desert with vegetation nourished by precipitation. That's why, when you search "Atacama" online, you'll see hundreds of photos of rivers and green slopes where alpacas graze peacefully. There are also photos of quite well-appointed towns, whose rosy-cheeked residents never reveal that they live in the driest desert on the planet.

Flora and Fauna of the Atacama

(Not)Absolutely Dry

But there are also plenty of photos of "Martian" landscapes—there are dozens of tourist routes to suit every taste in the center of the Atacama, from short scenic tours to circular routes through rocky, high-altitude terrain. Frankly, there's not much to see along the way—the bland and monotonous landscape becomes boring after just a few hours of driving, so a tour to the observation decks is quite sufficient. Everyone flocks to the viewpoints at sunset, when the setting rays paint the slopes yellow.

The Valley of the Moon in Atacama at sunset

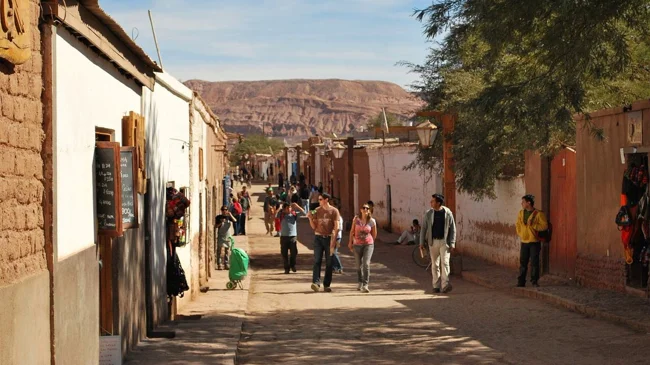

The center of life in Atacama is the tiny town of San Pedro de Atacama, which caters entirely to tourists. Situated at 2,400 meters above sea level, travelers there must adapt to the altitude for a while. Some take pills, others use local remedies made from coca leaves. If all goes well, the discomfort subsides the next day, and you can begin sightseeing.

San Pedro de Atacama is always crowded with tourists.

And there are quite a few of them. First of all, the Valley of the Moon and Death Valley are two areas with roughly identical landscapes. In the former, sand dunes and bizarre rock formations interspersed with salt layers create an otherworldly feel. In the latter, mineral outcrops paint the landscape in a variety of colors. This valley was named "Death Valley" in ancient times, when people who wanted to cross it were forced to stay there forever due to a lack of water.

Death Valley in Atacama

Speaking of humidity, precipitation in the heart of the Atacama is extremely rare, and the dryness of the air is felt throughout the body, immediately followed by a sticky feeling in the mouth. But the city has plenty of water. It's extracted from underground springs, so tourists can enjoy unlimited showers in the guesthouses. It rains here, and even snows—the last time it did was in late June 2025. So, calling this part of the Atacama the driest wouldn't be an understatement. However, if you drive 150 kilometers north of the city, you'll find places where the earth hasn't seen snow or rain for a couple of hundred years. It's all the more surprising to discover abandoned settlements there. These settlements are, in fact, the reason why people organize car tours deep into the desert. The fact is, people used to mine saltpeter in the Atacama and build mining towns. But the underground reserves were depleted by the late 1940s, and people learned to synthesize saltpeter. So the residents abandoned the settlements, but the extremely dry climate preserved all the buildings intact.

The abandoned mining town of Humberstone in the Atacama

The residents of these towns either had to bring in water or obtained it using fog collectors—simple nets stretched between poles. Drops of fog settled on the mesh, then condensed and flowed into special gutters. Significantly improved, these devices still exist today. Another Atacama attraction is the El Tatio geyser valley, the highest in the world and the third-largest in terms of active jets. Not everyone can visit it due to its altitude of 4,300 meters above sea level. However, those who do make it can enjoy not only fountains of water and steam, but also numerous thermal springs in which to bathe. The temperature there is quite comfortable and suits all tastes: from 25°C to 40°C.

Geysers in the El Tatio Valley, Atacama

It's especially pleasant to soak in such a natural bath after the modest outside temperature, which in the Atacama highlands often drops below freezing. Generally, the Atacama is a rather extreme place in terms of temperature fluctuations. In summer, travelers can languish in the heat and scorching sun, which heats the air to 40°C. And at night, they can freeze at freezing, wrapped in blankets and ponchos. It's certainly not a record—in the Sahara, temperature differences reach 50°—but coupled with the dry air and high altitude, the Atacama is certainly one of the most unusual places on Earth. And yet, in this harsh, lifeless void are also the "eyes of humanity"—two of the largest telescopes on Earth—the Magellan Telescope and the Very Large Telescope (its official name). It's no surprise—the absence of clouds, artificial light, zero humidity, and the high altitude in the Atacama create ideal conditions for stargazing. There are 12 observatories in the desert, and two more are under construction—the Large Magellan Telescope and the Extremely Large Telescope (Chileans have a real problem coming up with names). When they are operational (planned for 2030), they will be the largest telescopes in the world.

Telescopes at the Chejnantor Observatory, Atacama

Not all Atacama observatories allow tourists, but getting to them isn't easy. Instead, it's better to drive five kilometers from San Pedro de Atacama and admire the numerous saltwater lagoons and the flamingos on their shores. These birds have adapted over hundreds of years to feed on crustaceans that thrive in saltwater. They aren't afraid of people, but getting close to them is prohibited—they're in a restricted area.

Chilean Flamingos, Atacama

In general, the tourist part of the Atacama is quite restrictive. You can't leave the road, you can't wander between the lagoons, and you can't feed the birds or animals (alpacas and vicunas). Anything you can do comes with an extra fee. For example, visiting the observation deck or entering Death Valley costs money. In the Atacama, all you can do for free is admire the distant mountains. Or visit the "Hand of the Desert"—an unusual monument, a photo of which will complete the story of the driest non-polar desert on the planet.

The Hand of the Desert, an Atacama monument

The 11-meter-tall, open palm is made of reinforced concrete and, according to the artist, represents melancholy, loneliness, and human helplessness in the face of nature. The palm is a magnet for tourists and is constantly covered in graffiti. However, volunteers periodically clear it of this "artwork." However, not for long.