Scientists want to find out why archaeologists sometimes find preserved brains in ancient skulls (4 photos)

Scientists are trying to explain a rare archaeological phenomenon - a “preserved” human brain. The new study examined 4,400 specimens, some of which are more than 12,000 years old. It has always been believed that the brain is one of the first to decompose after a person’s death, but it turns out that this is not always the case.

The brain is believed to be one of the first human organs to decompose after death, forensic anthropologist Alexandra Morton-Hayward of the University of Oxford and co-authors wrote in their study. That's why the archaeological discovery of a preserved brain is considered unusual, the researchers said in a paper published March 20 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Indeed, for an archaeologist to find the remains of undecomposed organic matter is a rare and significant event, and even more so the remains of a brain. Such discoveries from thousands of years ago occurred from time to time, and in each case they tried to explain the preservation of the brain by the influence of some factors. Mechanisms such as dehydration, freezing, saponification and tanning are known to preserve brains no older than 4,000 years. However, finds of more ancient brains are much less common.

Researchers have compiled an archive of 4,400 archaeologically preserved samples of ancient brains found on six continents and dating back to different eras. This was done in order to provide a serious scientific basis for the study and, perhaps, to identify a hitherto unknown conservation mechanism.

Scientists have found that brains preserved in the absence of other soft tissue indicate an unknown mechanism that may be responsible for the preservation of the central nervous system in particular.

“The preservation of some soft tissues has been well studied. Dehydration and freezing - remember Egyptian mummies or frozen bodies,” Alexandra said in an interview with Science. - Sometimes fat in the body after death can turn into a soap-like substance that preserves tissue - this process is called saponification. And in peat bogs, the acid in sphagnum moss exposes soft tissue to a tanning process that often preserves brain tissue. But in this work we identified a fifth category: hundreds of brains that persist even when all the other soft tissues of the body have decomposed.”

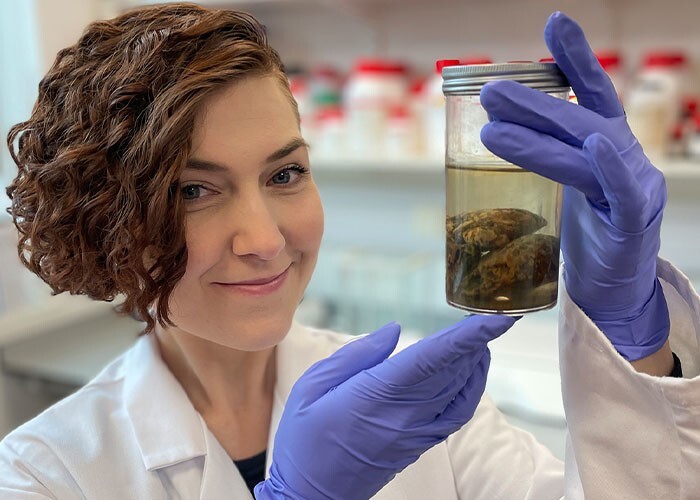

Forensic anthropologist Alexandra Morton-Hayward, one of the study's authors

The researchers identified a total of 4,405 preserved human brains from 213 unique sources from every region of the world except Antarctica. They compared the amount of preserved human brains with other soft tissues in archaeological databases and found that while internal soft tissues such as muscle and intestine are rare, preserved brains are much more common. This suggested that brains were preserved more often than previously thought.

“Based on the findings, I believe it is something related to the central nervous system because the brain has unique biochemistry,” Alexandra told Science. “The brain contains fats that are not found anywhere else in the body, and sulfur-containing proteins that are part of the brain’s signaling mechanism. I think it all comes together to form a stubborn material that can last a very long time.”

Ancient brains may provide new and unique paleobiological insights that will help us better understand the history of major neurological disorders, the cognition and behavior of past humans, and the evolution of neural tissues and their functions, the scientists say in their paper.

Regarding the ethical aspects of working with the brain of a long-dead person, Alexandra explained that in the UK, research on human soft tissue is regulated by a law known as the Human Tissue Act (HTA). If the fabric is more than 100 years old, the material is considered not to be subject to the HTA.

“But obviously, no matter how old they are, we still want to treat those remains with respect,” she added. “I always remember that these are people.”