Giant nuggets of Michigan, left over from glaciers (10 photos)

In the 17th century, hunters working on Lake Superior in North America learned from local tribes of an incredible boulder on the banks of the Ontonagon River. Legends described the boulder as the size of a house and weighing five tons. But most importantly, it was composed entirely of pure copper.

Rumors of an unclaimed treasure prompted many adventurers to set out in search of it. Soon, the boulder was indeed found, and rumors of its nature were confirmed.

A 19-ton specimen of native copper at the A.E. Seaman Museum at Michigan Technological University

However, for unknown reasons, no one competed for possession of the trophy for almost two hundred years. It wasn't until 1766 that merchant Alexander Henry, upon seeing it, was so astonished that he estimated its weight at ten tons. He noted that the copper was so pure and malleable that he could easily chip off a large piece.

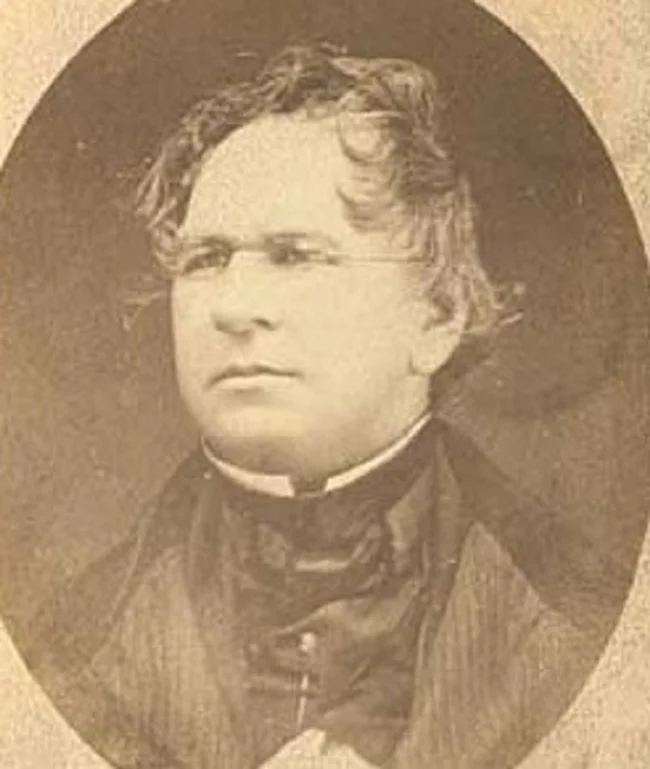

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft — American geographer, geologist, and ethnographer

Inspired by these stories, geologist Henry Schoolcraft set out to search for the legendary boulder. Having discovered it in 1819, he was disappointed: the boulder, now known as the Ontonagon Boulder, turned out to be much smaller than the legends had suggested. Schoolcraft estimated its weight at only one ton, but he was also mistaken, albeit on the smaller side. The boulder's actual weight was later determined to be around 1,680 kilograms.

The Ontonagon Boulder, on display at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History

The detective story revolves around Detroit entrepreneur Julius Eldred. He acquired the boulder twice: first from the indigenous people and then from the federal government.

The boulder weighs approximately 26.6 tons.

Overcoming enormous difficulties, he dragged the boulder through the forest, floated it down the river on a raft, and delivered it by ship to Detroit, where he put it on public display. After a legal dispute with the authorities over ownership, the government was forced to buy the boulder back, paying Eldred four times what he had originally paid for it. Today, the Ontonagon Boulder is kept in the vaults of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Giant copper boulders like the Ontonagon Boulder once dotted the Keweenaw Peninsula in northern Michigan. About 10,000 years ago, the two-kilometer-thick glacier that covered the region began to melt. As the ice moved, it broke off chunks of native copper from the rock and carried them along. This created masses of nearly pure copper that remained on the surface after the glacier retreated. Relatively recently, a huge nugget was found in the forest, considered the world's largest floating copper specimen. It weighs approximately 28 tons and contains over 90% copper.

The main deposits of this copper were formed a billion years ago by ancient eruptions, creating the only deposit on Earth where native copper of 97% purity occurs on an industrial scale. Subsequent glaciation cycles eroded the upper layers of rock, exposing the copper ore and allowing glaciers to tear massive chunks of copper from the rock and scatter them across the area.

Native Americans began exploiting this resource about seven thousand years ago. By 3000 BC, copper was being used to make spearheads, axes, knife blades, and jewelry. The nuggets were so pure that tools were forged directly from the piece, without smelting. Smelting technology for producing a more refined metal developed much later among the Native Americans.

Industrial mining began in the mid-19th century, and for the next hundred years, northern Michigan was plunged into a copper rush. Almost all the surface nuggets of that period were smelted.

Native American Copper Artifacts

Today, only a few such examples—from pocket-sized to the size of a small car—can be seen in various museums and collections across the state.