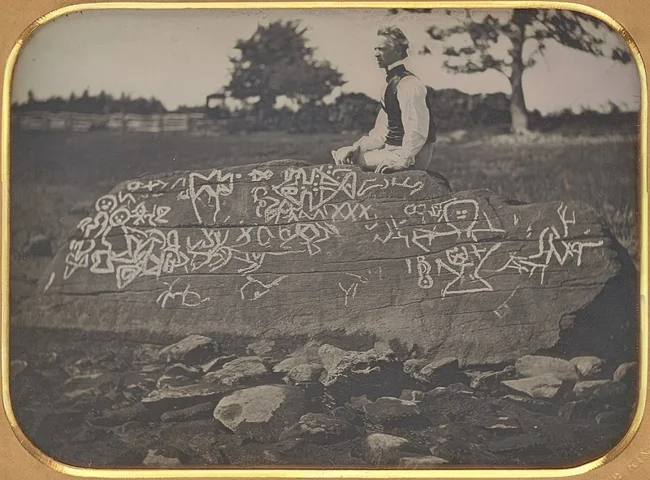

On the banks of the Taunton River in Berkeley, Massachusetts, there is a small museum with a single, but massive exhibit - a 40-ton rock that was fished out of the river and installed there in 1963 - the famous Dayton Rock, named after the former city of Dayton where it was found. The rock's glory lies in the illegible inscriptions carved into its face, which have puzzled scientists since the 17th century.

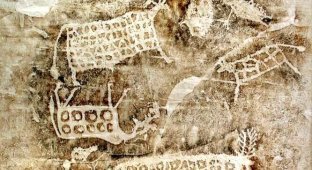

The petroglyphs, which consist mostly of straight lines and geometric shapes, are accompanied by very simple drawings of people, as well as primitive writing. They look like random scribbles made by people who had nothing better to do, but people are sure that they contain a secret message.

Dighton Rock is approximately five feet tall, 10 feet wide and 12 feet long. The surface with the inscriptions is inclined and once faced the sea, where it could be seen from any boat or ship. Therefore, over the centuries, it has been suggested that the carvings were a message left to attract the attention of marine explorers passing this way.

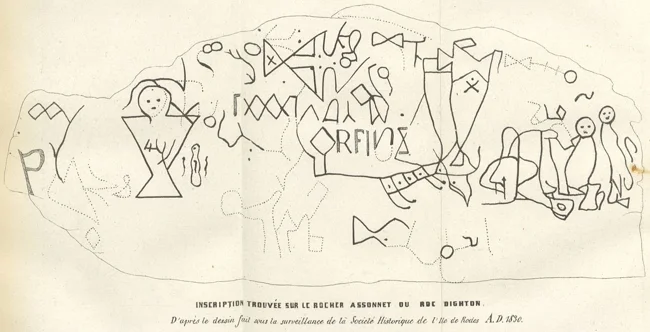

One of the first mentions of Dighton Rock dates back to 1680, when English colonist Reverend John Danforth made a drawing of the petroglyphs, which is preserved in the British Museum. However, Danforth's drawing contradicts other reports about the rock made at the same time. In 1690, the Reverend Cotton Mather described the rock in his book:

Among other curiosities of New England, one of them is a mighty rock, on the perpendicular side of which, by the river, which at high tide covers part of it, is very deeply engraved, no one living knows how or when, about fifty lines filled with strange symbols, which suggest strange thoughts about those who were here before us, as well as strange forms in this complex monument.

In the 19th century, many popular publications and public figures mentioned the rock. Poet and critic James Russell Lowell suggested that presidential candidates mention it in letters to newspapers: "If letters are to be written, the Dayton Rock hieroglyphics or cuneiform writing might be used to advantage, each new decipherer of which is capable of deducing a different meaning." Lowell made other references to the rock in his widely distributed satires and may have helped popularize it.

Various versions and theories

One of the most authoritative theories was put forward in 1837 by Danish scholar Carl Christian Rafn, who suggested that the carvings were made by Vikings and represented the Norse saga of Thorfinn Karlseln and his voyage to the North American coast to a place called Hop, where his wife Gudrida gave birth to his son Snorro. Rafn's theory attracted the attention of the Rhode Island Historical Society, which contacted their friends in Denmark, and together they found enough evidence to state that Hop was on the Taunton River.

Rafn's research generated international enthusiasm, and by 1837 the theory of pre-Columbian Viking exploration of North America had gained near-universal acceptance. Dayton Rock was the final link in a long line of evidence. Unfortunately, the Viking rock theory was shattered in 1916 by Professor Edmund B. Delabarre of Brown University. Delabarre found gross discrepancies between the society's actual drawings and the doctored copies reproduced in Rafn's book. Rafn had apparently added numerous lines to the drawings to support his theory.

While studying the inscription, Delabarre discovered among the lines and markings the name "Miguel Cortereal" and the date "1511." Delabarre claimed that the message was abbreviated Latin in the Portuguese style, which could be translated as: "I, Miguel Cortereal, 1511. In this place, by the will of God, I became the chief of the Indians."

But who was Miguel Cortereal? Miguel Cortereal was a Portuguese explorer who set out from Lisbon in 1502 to search for his brother Gaspar, who had been lost two years earlier near Newfoundland. The expedition apparently reached the site where Gaspar's party had landed, after which the three ships went their separate ways to search. Later, the ship carrying Miguel failed to show up for the appointed meeting. The other two set off on their return voyage to Portugal, and Miguel and his ship were never seen again.

Delabarre proposed that Miguel Cortereal reached Mount Hope Bay in 1502 and sent men ashore at Dayton Rock. Perhaps there was a battle with the Wampanoag Indians, perhaps a shipwreck, or perhaps for some other reason, Miguel joined the Wampanoags. Cortereal lived with the Wampanoags for several years, keeping a close eye on ships on the coast. But by 1511, with hopes of rescue fading, he carved a message into the rock, where it would be preserved for future generations.

Delabarre's theory was widely accepted in Portugal, but not widely accepted elsewhere.

Other theories attribute the carvings to the Phoenicians and even the Chinese, who author Gavin Menzies says arrived in the Americas before Columbus. Scientists continue to endlessly argue about the Dayton rock, but representatives of the scientific community have not yet come to a consensus.

Add your comment

You might be interested in: