Floating sawmills: a controversial project by British shipbuilders (5 photos)

Before the Industrial Revolution, the British shipbuilding industry was entirely dependent on timber and other materials—such as masts, tar, and pitch—from the Baltic region. For a powerful maritime power, such a daunting dependence on imported raw materials not only undermined its defenses but also exacerbated the growing trade deficit with the Baltic states.

The American colonies met only a small portion of Britain's timber needs, despite New England's nearly inexhaustible forest resources. The reason was the vast distance between the mother country and the colonies, making transatlantic shipping unprofitable.

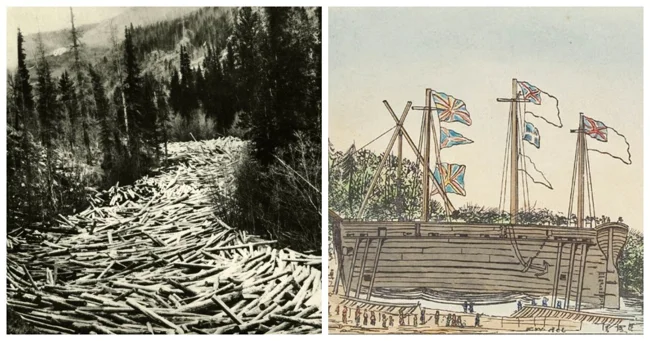

Logs await the spring floods to be carried into the Columbia River in the Canadian province of British Columbia.

The American colonies met only a small portion of Britain's timber needs, despite New England's nearly inexhaustible timber resources. The reason was the vast distance between the mother country and the colonies, making transatlantic shipping unprofitable.

In the early 18th century, the British government launched a number of initiatives to encourage the use of colonial timber over Baltic timber. These included subsidies for North American manufacturers and a ban on the export of colonial timber to countries other than England. These measures had little impact on imports. Baltic timber continued to dominate the British market and was used by both the military and merchant navy, as American timber was still three times more expensive.

During the Napoleonic Wars, French military successes and the Baltic blockade threatened the stability of supply, and Britain again turned its attention to its former American colonies. Through a series of acts in 1809 and 1810, it imposed increasing duties on Baltic timber, while colonial timber was subject to only a nominal tax. This system led to a rapid growth in the American timber trade, and by the end of 1809, British imports had more than tripled compared to two years earlier. By 1812, American timber accounted for over 60% of all British imports.

In the early 18th century, the British government launched a number of initiatives to encourage the use of colonial timber over Baltic timber. These included subsidies for North American producers and a ban on the export of colonial timber to countries other than England. These measures had little impact on imports. Baltic timber continued to dominate the British market and was used by both the military and merchant navy, as American timber was still three times more expensive.

During the Napoleonic Wars, French military successes and the Baltic blockade threatened the stability of supplies, and Britain again turned its attention to its former American colonies. Through a series of acts in 1809 and 1810, it imposed increasing duties on Baltic timber, while colonial timber was subject to only a nominal tax. This system led to a rapid growth in the American timber trade, and by the end of 1809, British imports had more than tripled compared to two years earlier. By 1812, American timber accounted for over 60% of all British imports.

However, this advantageous tariff system was a temporary wartime measure, and after peace returned to Europe, debates about its future arose. In 1821, tariffs on European timber were reduced and imposed on American timber for the first time. The new system still gave American producers an advantage, and timber imports even increased. Timber prices rose, wages increased, and everyone rushed into the promising business.

At the height of this frenzied activity, two Glasgow shipbuilders, Charles and John Wood, in pursuit of quick profits, developed a technology for the mass import of timber. Their plan was to build a gigantic ship—much larger than the largest existing vessel—that would be crammed full of timber and sail across the Atlantic. Upon arrival, it would be unloaded, the structure itself dismantled, and sold as lumber. This way, the importers would profit doubly: first from selling the cargo, and then from avoiding duties on the timber used to build the ship.

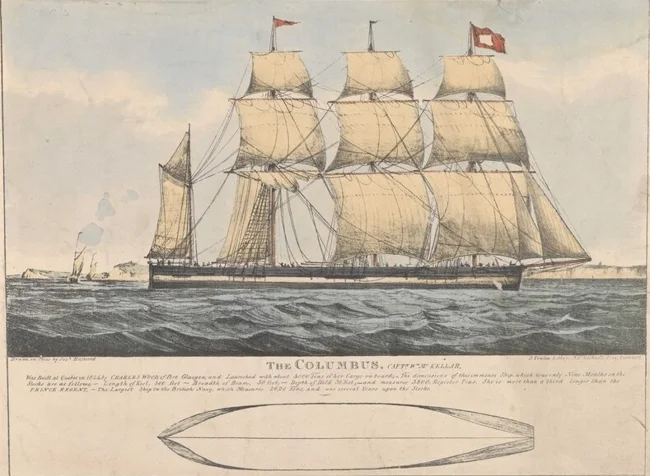

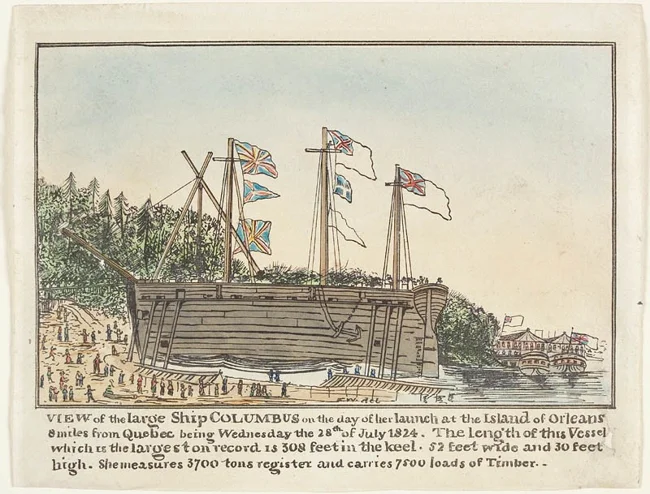

In 1824, Charles Wood traveled to Quebec to oversee the construction of the first one-day ship, the Columbus. Its dimensions were colossal: 91 meters long, 15 meters wide, and almost 7 meters high. The vessel weighed a staggering 3,690 tons—more than ten times the tonnage of an average ship. The ship was built with minimal expense. The hull was composed of thick, rough-hewn logs, uncaulked at the seams so they could be easily dismantled without damaging the wood. The bottom was wider than the deck, giving the entire vessel a clumsy and crude appearance. According to a correspondent for The Times, "The Columbus was a colossal mass of timbers, hammered together for commercial purposes, without the slightest regard for beauty and with almost no regard for the principles of naval architecture."

The Columbus's journey across the Atlantic was full of adventures, as one would expect from such a precarious vessel. Due to poorly caulked seams, the ship sprang hundreds of leaks as soon as it touched the water. The crew worked nonstop for seven weeks, pumping out water from the hold. By the time they arrived in the English Channel, there were already about four meters of water in the hold.

The Columbus entered the Port of London with great fanfare. She carried 6,300 tons of timber as cargo, plus another 3,690 tons of the ship itself. In a single voyage, the Columbus delivered over 10,000 tons of timber across the Atlantic, worth £50,000. The venture was a resounding commercial success. But at that point, greed overrode the original plan to dismantle the ship, and the Columbus's owners sent her off to pick up more cargo. Three weeks into the return voyage, the ship was caught in a severe storm, broke apart, and sank.

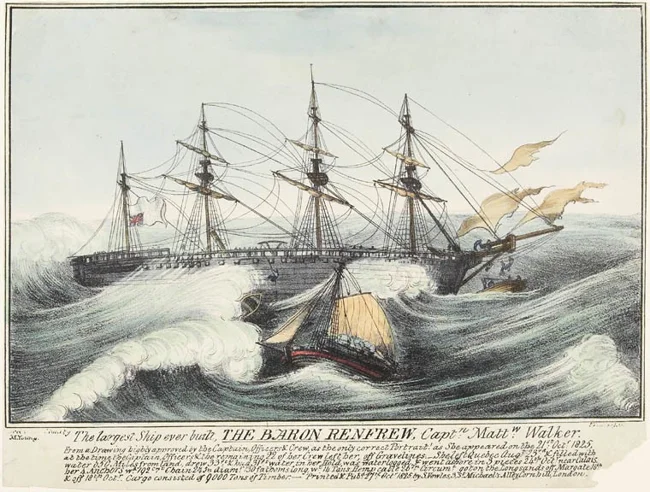

Meanwhile, a second similar vessel, the Baron of Renfrew, was under construction in Quebec. It was approximately the same length as the Columbus, but wider and deeper, increasing its weight to 5,880 tons. Its gross weight at launch was over 15,000 tons, including cargo; 2,000 tons of this amount were masts for the Admiralty—the largest ever shipped from Canada. After a perilous Atlantic crossing, the ship ran aground on the Goodwin Sands off Long Sand Head in the English Channel. When it became apparent that the vessel could not be refloated, the crew abandoned it. The Baron Renfrew soon broke apart, and its timbers washed up on the coast of France and Flanders.

The owners of both the Columbus and the Baron Renfrew suffered serious financial losses, but from an engineering perspective, the venture was a success: both ships completed their planned voyage east across the Atlantic. The Columbus was lost due to a deviation from the original plan and being sent on a second voyage. The Baron Renfrew perished not due to structural problems, but due to the incompetence of its crew. Nevertheless, the loss of both vessels brought an end to the brief era of fly-by-night ships.