X for "Tirpitz". "Source" of future triumph (9 photos)

The battleship Tirpitz, commissioned into the Kriegsmarine in February 1941, was a major problem for the Allies. Although the ship saw little combat, her very presence in the Norwegian fjords posed a constant threat to the Arctic convoys. The most notable example was the tragically infamous PQ-17 - the convoy was disbanded while waiting for the Tirpitz and her escort, which resulted in catastrophic losses.

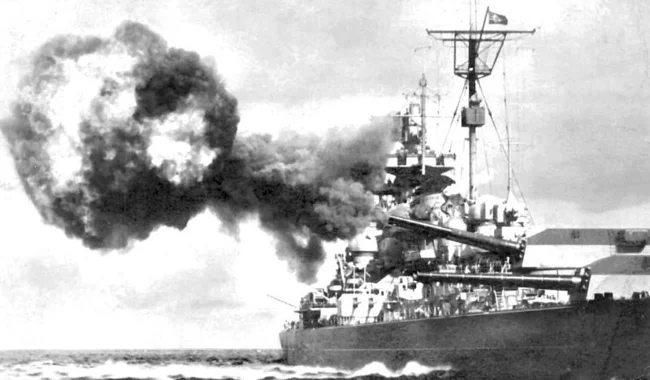

A shot from the 381-mm main battery guns of the turret No. 3 "Caesar" of the battleship Tirpitz, 1941, Baltic Sea. A distinctive feature is noticeable - the ship's turrets are painted red at the top

Later it became clear that the fears were partly exaggerated: after the sinking of the Bismarck, the German command avoided the risk of direct clashes with large enemy forces. Nevertheless, during the war, the British fleet experienced significant difficulties in countering the battleship. Safely hidden in the fjords and protected by anti-aircraft forces, the Tirpitz was out of reach of most British forces, especially given the lack of battleships in the Arctic region.

Eliminating this threat became a priority for Britain. The first major success was achieved in September 1943 during the sabotage operation Source.

The Success of the Raid on Alexandria

In December 1941, Italian commandos from the Decima Flottiglia MAS unit carried out one of their most daring and successful operations. Six fighters on three human-controlled torpedoes "Maiale" attacked the port of Alexandria - one of the largest and most guarded bases of the British Royal Navy. In just one night, the British lost the battleships Valiant and Queen Elizabeth for more than a year, which was a painful blow to the reputation of the Royal Navy at that difficult time.

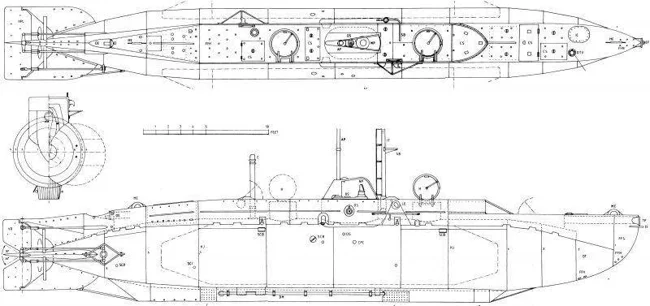

The Maiale (literally "little pig") human-controlled torpedo. The saboteurs directed the torpedo under the bottom of the target, set the fuse mechanism and secretly left the area. The TNT charge weighed 200-300 kg

Despite the fact that the sabotage did not go according to plan, and the commandos were captured, their professionalism was noted by the British themselves. "It seems shameful that the Italians should be so much better than we are at attacking ships in harbour," said Winston Churchill.

After the raid on Alexandria, the British lost all confidence in the security of even their most guarded bases. At the same time, they began training their own sabotage units.

Midget "X"

With the success of the Italians, the British Navy came to the conclusion that midget submarines were best suited for stealth attacks on large enemy ships. This is how Project "X" was born - compact submarines capable of moving both on the surface and underwater, quietly penetrating the target area and laying mines under enemy ships. The first models, X3 and X4, were built and tested in 1942. The tests revealed many technical shortcomings that required revision of the design. During one of the tests, the X3 sank due to a valve leak, but the crew was saved, the boat was raised and restored.

A schematic of the X-type midget submarine. The submerged displacement was 29.7 (some sources indicate 35) tons, the length was 15.8 meters, and the width was 1.8 meters, the economical speed did not exceed 4.5 knots

At the end of the same year, an updated version of the submarine was approved, and serial construction of the X5 modification began. The new layout included four compartments, a reinforced hull, a diesel-electric power plant, and space for a fourth crew member responsible for diving operations. Thus, the submarine's crew consisted of a commander, a helmsman, a motor mechanic, and a diver.

The armament consisted of two mines with a clock mechanism weighing about two tons each, which were attached to the outside of the hull. The mines were installed directly under the target without the crew having to go outside. To deliver the submarines to the operation area, they were towed by conventional submarines.

Thanks to the reinforced hull, the submarines could dive to a depth of 90 meters and travel up to 1,860 nautical miles at an economical speed. From the beginning of 1943, the crews actively trained in covert maneuvering, setting charges, and leaving the attack zone. By autumn, preparations were complete, and the X-boats were used in combat for the first time – against the British main target in Arctic waters, the battleship Tirpitz.

The Soviet Union's Contribution

Systematic aerial reconnaissance in the northern seas was carried out by the Soviet Union from the beginning of the war according to the plans of the headquarters of the Northern Fleet and the White Sea Flotilla. Reconnaissance flights were carried out once or twice a day, until the second half of 1944 exclusively during daylight hours. The most effective was aerial reconnaissance of the naval bases of Northern Norway. Particular attention was paid to the Altenfjord, a system of fjords in the north of the country, where the battleships Tirpitz and Scharnhorst were based in its most protected part, the Kohfjord. In the neighboring branch of the Altenfjord, the Langfjord, the heavy cruiser Lützow was stationed.

In early September 1943, some of the most experienced British Air Force reconnaissance aircraft were called in to reconnoiter the Altenfjord area, but due to extremely difficult weather conditions, the British were unable to photograph the German ships and terrain. Soon, this task was assigned to a Soviet pilot with extensive combat experience, squadron commander Captain Leonid Elkin.

"Grandfather Kalinin" presents Leonid Elkin with the Hero of the Soviet Union star, February 10, 1944. Elkin would not return from combat reconnaissance in Northern Norway just 10 days later. Died under unclear circumstances

On September 12, he flew out on a mission in extremely unfavorable weather conditions: solid clouds with a lower edge of about 300 meters, rain charges, snow, icing. Elkin demonstrated outstanding training and personal courage. He descended below the clouds and at an altitude of only 50 meters passed directly over the battleship Tirpitz three times, while under heavy anti-aircraft fire. Despite the constant shelling, he took photographs of the targets, waiting for the clouds to clear directly above the enemy base. The resulting images became the first clear images of German ships in the Altenfjord. This flight, according to British colleagues, was extremely risky, and "there would not be a single one among them who would dare to repeat it."

The intelligence obtained during Elkin's daring flight became a key element in the preparation of Operation Source. It allowed the British command to assess the location of obstacles and security, and identify weak points in the German positions. Additional information was provided by the Norwegian resistance - the brothers Thorbjørn and Einar Johansen transmitted information about the patrol schedule and the technical condition of the Tirpitz.

The beginning of the operation

The attack was planned for September 22, the day of the autumn equinox. This day provided the optimal balance between darkness and light: the nights were dark enough to recharge the batteries, and the daylight made it easier to visually navigate in the narrow and dangerous fjords. In addition, intelligence reported that it was on this day that maintenance was planned on the Tirpitz - the hydrophones were temporarily turned off, which significantly reduced the likelihood of saboteurs being detected.

Mid-September marked the departure point for six midget submarines, X5 to X10. Each was towed by a standard-displacement submarine: Thrasher (X5), Traculent (X6), Stubborn (X7), Sea Nymph (X8), Syrtis (X9) and Septer (X10). The 1,200-mile journey across the North Sea took eight days. Living conditions on board the midget submarines were so appalling that crew changes were required. The submarines were manned by temporary crews while under tow, with operational crews taking up their duties at the release points.

Battleship Tirpitz moored in Kåfjord. The L-shaped torpedo net around the ship is visible

The operation plan called for the mini-submarines to leave 60 miles from Altenfjord. From there, the submarines were to navigate the minefield on their own to reach their target in Kåfjord. They were to spend the night of September 21 off Brattholm Island to recharge.

The tasks were divided as follows: X5, X6 and X7 aimed at the Tirpitz, X9 and X10 at the Scharnhorst, X8 at the Lützow in Langfjord. However, the group suffered losses early on in the operation. The towing cable between X9 and the Syrtis broke under unclear circumstances, and the submarine disappeared without a trace along with its crew. X8 was lost after one of the mines depressurized its hull, but its crew was evacuated to the Sea Nymph.

Sabotage in Kåfjord

At dawn on 20 September, the remaining submarine tugs reached their starting points, approximately 60 miles west of Altenfjord. Between 18:30 and 20:00, the four small submarines separated from the tugs and headed for the Altenfjord. As a parting shot, Lieutenant Henty-Krier from X5 wished good luck to Lieutenant Place, the commander of X7. This was the last message from X5 - the boat and its crew had disappeared without a trace.

Lieutenant Henty-Krier and the crew of the midget submarine X5. He and the entire crew were missing

Submarine X10, commanded by Lieutenant Hudspeth, soon suffered technical problems that could not be repaired. The British command cancelled the planned attacks on the Scharnhorst and Lützow, and the crew of X10 evacuated to the Septer.

Meanwhile, X6, commanded by Lieutenant Donald Cameron, and X7, commanded by Lieutenant Basil Place, successfully cleared the minefields. On the evening of 21 September, both boats took up waiting positions near the Brattholm Islands at the entrance to Kåfjord. The following day, shortly before sunset, the protective boom around the Tirpitz was opened to allow the passage of a coasting vessel - an opportunity that Cameron immediately seized. Despite the damage to the gyroscope and the failure of the periscope, he managed to get X6 under the battleship and plant the charges.

The submarine X7 also reached the Tirpitz, but became entangled in the anti-torpedo net. Nevertheless, the crew managed to mine the ship. During the retreat, the submarine was damaged and again got stuck in the net. Two survived - including Lieutenant Place - the rest died in the sunken submarine.

On board the battleship

In Kåfjord, the morning of September 22 began calmly. The watch on the hydrophones ended at 05:00 - the devices needed servicing. Due to their temporary shutdown, observation was assigned to visual lookouts. At 07:07, one of them noticed a slight disturbance in the water within the torpedo nets, which was mistaken for a porpoise - a cetacean common in those waters.

Battleship Tirpitz in Kåfjord shortly before the attack by British saboteurs. September 1943

In fact, it was submarine X6, which had just hit an underwater rock and briefly surfaced. Five minutes later, it resurfaced, and this time it was identified as an enemy. During the alarm, the signal to seal the compartments was mistakenly sounded - most of the crew did not realize the immediate threat. The submarine was too close to fire and went under again. A few minutes later, X6 surfaced again, and its crew was detained from the boat. Despite the arrest, the British managed to sink the submarine. The Germans, not noticing signs of an attack, decided that they had prevented sabotage.

At 07:40, a second submarine, X7, was discovered. It had already laid charges and was trying to leave the area, but was fired upon by destroyers and seriously damaged by a depth charge. The submarine became entangled in the net, and two surviving British were captured. The Tirpitz's commander, Hans Meyer, not knowing whether the attack was over, ordered the ship to go ahead and change course. However, the maneuver required increasing the pressure in the boilers, which would take at least an hour.

At 08:12, two powerful underwater explosions of eight tons of ammothol were heard. The battleship rose about a meter, and about 1,400 tons of ice water gushed inside. The generator compartments were flooded, most of the electrical equipment was out of order, the propellers were jammed, the main caliber turrets and anti-aircraft batteries were damaged, the rangefinders and radars were disabled. Two Arado seaplanes were also destroyed.

Tirpitz after Operation Source. The Karl Junge power plant, which supplied electricity, is located alongside the battleship. Anti-torpedo nets are visible in the foreground

After the attack, the rescue ships Karl Junge and Watt were sent to the damaged battleship. Despite the strong list, the command decided to carry out repairs on site. The decision to restore the ship was made on September 25 with the personal participation of Hitler. The Tirpitz's power structure was seriously damaged, and it was impossible to return it to full combat readiness.

The repair work was completed only in April 1944. For successfully disabling the battleship Tirpitz for many months, several participants in the operation received state awards. Despite the fact that none of the targets were destroyed, Operation Source became the first serious success of the British saboteurs.