A Dynasty of Time Traders and Their Brilliant Idea for Making Money (7 photos)

Mechanical clocks of the 19th century and earlier were not particularly accurate timekeepers. After a couple of days, such clocks could no longer reliably determine and show time. They needed to be calibrated, and this was usually done by watchmakers.

One of the reliable sources of accurate time after it became possible to determine it was observatories. An astronomer with a telescope could determine the exact time by looking at the sun and stars in the sky. This time was then transmitted to the population and ships using audiovisual signals, such as a cannon shot or a flag raised.

Ruth Belleville at the Royal Observatory Greenwich

The Royal Observatory in Greenwich became the main timekeeper in her country. To help sailors in the port and other people in direct line of sight from the observatory to synchronize their watches, a so-called time ball was installed inside. It fell every day at exactly one o'clock on the top of the observatory. This is still the case today.

Later, the institution installed a large clock on its gates so that anyone could see the exact time at any moment, rather than languishing in anticipation of a signal. But to see this clock, people had to travel from their homes and offices all over London to the observatory, which was inconvenient.

Greenwich Observatory

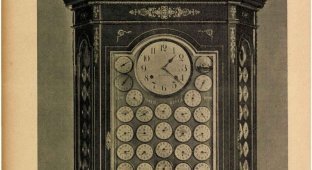

John Bellville, an employee of the Royal Observatory, had a plan. Instead of forcing people to come to the observatory, he would let time come to the people. Each day, Bellville would set the time on a pocket watch at the observatory, then travel around London, providing accurate information for a small subscription fee. Bellville had about two hundred customers, including railways, watchmakers, shipping companies, and wealthy individuals who wanted their watches to tell the right time.

The watch that Belleville used was a modern John Arnold pocket chronometer, which could tell time to a tenth of a second. It was originally made for the Duke of Sussex and had a gold case. When the watch was given to John, he changed the case to a silver one, as he was afraid that a gold watch would be stolen by thieves.

John Arnold with his family

John continued in the business until his death in 1856. His widow, Maria, was then given the privilege of continuing the business, and continued in the business until her retirement in 1892, when she was already in her eighties. Maria then passed the family business on to her daughter Ruth.

Maria Belleville

When Ruth Belleville took over the business, she faced stiff competition from the various telegraph time services that could communicate the time by telegraph. If the equipment was available, it was possible to automatically synchronize their clocks using time signals transmitted directly from various observatories. But homes and small businesses did not have their own telegraph stations. So they continued to rely on Ruth Belleville.

Ruth Belleville

John Wynn, director of the world's largest telegraph time signal company, even publicly ridiculed Ruth Belleville, saying that "her methods are comically out of date." He also hinted that she "maybe exploit her femininity for profit."

After his speech was published in The Times, Belleville was besieged by reporters interested in her business and the potential scandal that Wynn's comments hinted at. Belleville managed to cope with the situation, and the publicity she received led to increased sales. According to Belleville, all Wynn managed to do was give her free publicity.

Ruth Belville supervises the adjustment of an office clock

Like her mother, Ruth Belville continued selling time into her eighties. She retired in 1940. By then, modern technology had outpaced Ruth's beloved pocket watch, and it could no longer compete with more efficient, reliable, and affordable forms of communication. In all, the Belville family business lasted 104 years, from 1836 to 1940.

Before Ruth died in 1943, she donated her watch, nicknamed "Arnold", to the Clockmakers' Company of London. It is now on display at the Clockmakers' Museum in London.