Who invented Braille and when (2 photos)

In 1819, 10-year-old Louis Braille became the youngest student ever accepted to the Royal Institute for Blind Children in Paris. Eager to learn to read and write, Braille was disappointed to learn that the school's library only had three books.

This was because the only way to print books for the blind at the time was by embossing the letters. Printers would carve each letter in mirror image on wooden blocks and press them into thick wax paper, creating rows of raised letters. A blind person could learn to distinguish these letters with his fingers, but the process of creating them was so labor-intensive and expensive that very few books existed.

Years later, Braille recalled his first impressions as a talented blind student, when he found himself virtually cut off from the world of knowledge and discovery.

“If my eyes cannot tell me about people and events, ideas and doctrines, I must find another way,” he said. “If I cannot find a way to read and write, to understand the life around me and what came before me, I will simply take my own life.”

Through inspiration and persistence, Louis Braille created a simple and ingenious system that allowed the blind and visually impaired to read quickly and almost effortlessly. And he did it all before his 16th birthday.

Accident

Louis Braille was born in 1809 in the small French village of Coupvray, near Paris. He was the youngest of four children and was born healthy, with normal eyesight.

His father, Simon-René Braille, was a harness maker. Little Louis, being an inquisitive child, often sat next to his father in the workshop and played with pieces of leather. One day, while Simon-René was talking to a customer, 3-year-old Louis picked up an awl from the work table. Imitating his father, he tried to pierce the skin with the sharp instrument, but his hand slipped.

The awl pierced the boy's left eye. Doctors in the village did their best, applying herbal ointments, but the deep wound soon became infected. In addition, the infection spread from the left eye to the right.

“When will the morning come?” little Braille asked in despair as his vision gradually faded and plunged him into darkness.

A Rare Opportunity to Learn

In the early 19th century, most blind people had little chance of living a full life. People with disabilities were often placed in boarding schools, used as “comic” entertainment, or left to beg on the streets.

However, Louis Braille was fortunate to grow up in a loving family that treated him like other children. He attended the village school, played musical instruments, and did chores. His father, Simon-René, taught his son the alphabet by hammering round-headed nails into a board to form letters. Louis imitated the shapes by creating letters out of straws.

At school, it was immediately apparent that Braille was precocious. Despite his lack of sight, he was ahead of all his classmates in his grades. A teacher at the village school suggested that Louis' parents send him to the Royal Institute for Blind Children, the world's first school for the blind. So Braille received a scholarship and entered the institution at the age of 10.

Limitations of Embossed Printing

The Royal Institute for Blind Children was founded in 1784 by Valentin Haüy, a young French educator who was shocked by a street performance that made fun of the blind. Haüy began his work with one student, a blind beggar named François Leseur.

To teach Leseur to read, Haüy used wooden blocks with letters of the alphabet and assembled them into words on a special stand. One day, he accidentally noticed that Leseur could distinguish the indentations on the back of printed pages.

This gave Haüy the idea of creating raised letters on sheets of wax paper. Through numerous experiments, he developed the first primitive system for teaching the blind to read. It was this system that Louis Braille encountered when he arrived at the institute in 1819.

However, when Braille finally got his hands on three books with raised letters, he was disappointed. Reading such large and awkward characters was so slow that, even with an excellent memory, Braille forgot words from the beginning of a sentence by the time he got to the end.

“I have a hard time imagining how anyone can read fluently with raised type,” says Ariel Silverman, director of research at the American Foundation for the Blind. “The letters are too big for the fingertips. When I read Braille, I can run through a line in a few seconds."

Captain Barbier's Raised Dot System

Young Louis Braille was determined to find a way to read and write as fluently as sighted people. Inspiration came in 1821, when a retired French army captain visited the Royal Institute.

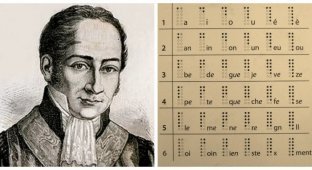

Captain Charles Barbier served under King Louis XVIII and was part of the Signal Corps. He developed a secret language for military communications, which the army rejected, but Barbier believed that his system could revolutionize the way the blind learned to read and write.

On the battlefield, any sound or flash of light could give away the location of soldiers, so Barbier called his system "night writing" because it could be written and read in complete silence and darkness.

The "night writing" system used raised dots punched into the paper that could be recognized by the fingers. The symbols were created on a grid with two horizontal and six vertical cells (12 cells in total). The number and arrangement of the dots determined the sound of the symbol, and words were conveyed not by letters, but by sounds.

When Barbier presented his system at school, 12-year-old Braille was amazed. The raised dots were much easier and faster to perceive than the embossed letters. However, the more Braille experimented with the system, the more shortcomings he found.

He came to the conclusion that the 12-dot grid was too cumbersome, since one word sometimes required up to 100 dots. In addition, since the symbols conveyed sounds, not letters, blind students could not learn correct spelling. Barbier's system also did not have symbols for punctuation marks, numbers, or musical notation. How then would the blind be able to learn mathematics or write music?

Braille's "Simple and Elegant" Solution

Inspired but also disappointed by Barbier's "night writing" method, Braille decided to improve the system. He took Barbier's tools - a sharp stylus and a special ruler with grids - and began to work on improving the method.

For three years, while at the Royal Institution, Braille devoted all his free time to developing his own version of the dot writing system.

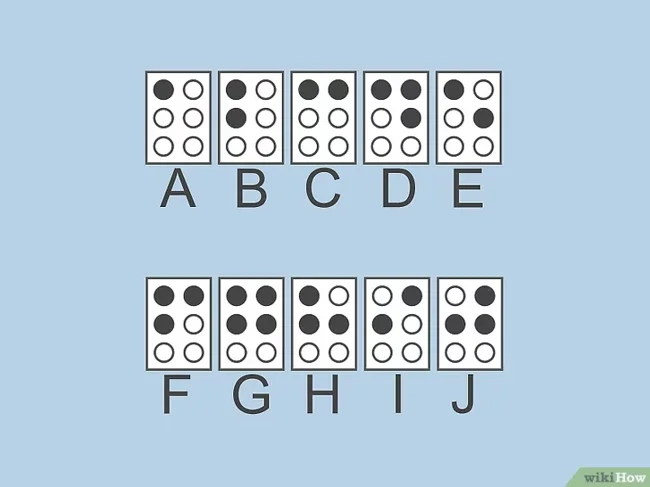

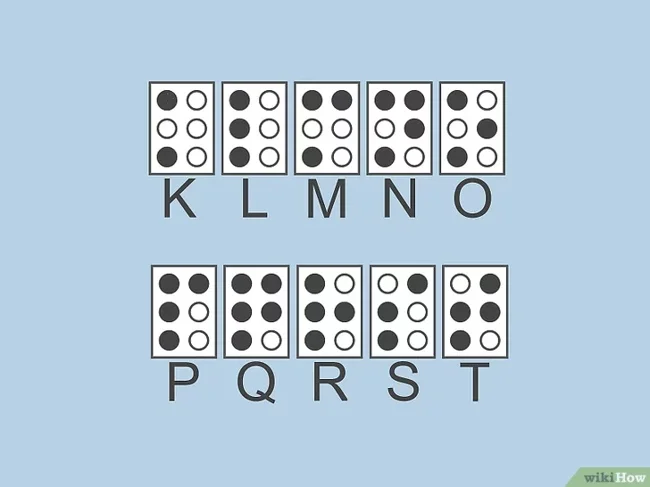

The first important step was to reduce the size of the grid by half: now it consisted of two cells wide and three high, for a total of six positions. Then he changed the principle of encoding symbols: each combination of dots in the Braille system now denoted a letter of the alphabet, not a sound. The letters A through J were created by different combinations of four dots in the upper part of the grid. For the letters K through T, the same combinations were used, but one dot was added in the bottom row. The letters U through Z followed the same principle, with the addition of two dots at the bottom.

The ability to represent numbers with a special symbol before the letters was also introduced, and Braille developed punctuation marks.

“The system is so simple and elegant,” says Silverman, who is blind herself. “There are only 64 possible combinations of dots in Braille. The simplicity of the system makes it easy to learn, easy to print, and standard for use. This has many advantages both in teaching and in the production of materials.”

Braille demonstrates his system at age 15

In the fall of 1824, when Louis Braille was 15, he presented his dot writing system to the director of the Royal Institute, Dr. Alexandre René Pigneur. Braille sat with a stylus, a ruler, and paper while Pigneur read him a long article.

"You can read faster," said young Braille, moving the stylus quickly across the page. Ten years later, at an exhibition in Paris, Braille was able to punch 2,500 dots per minute.

When Pigneur finished reading, Braille flipped back to the beginning of his notes, ran his fingers over the raised dots, and reproduced the entire text word for word. The director was amazed.

Pigneur immediately introduced Braille training at the institute and wrote to the French Minister of the Interior with a proposal to introduce the method at the national level. However, his recommendation was ignored.

At the age of 19, Braille became the first blind teacher at the Royal Institution and published his dot-writing system in a book called A Method of Writing Words, Music, and Plain Songs by Dots, for the Use of and Adapted to the Blind.

Braille's Legacy

Louis Braille's revolutionary six-dot system was not adopted outside the Royal Institution during his lifetime. Braille died of tuberculosis in 1852, aged just 43.

It took almost a century for the world to fully accept Braille as the official writing system for blind and partially sighted people. After much debate about alternative systems such as New York Point, English-speaking countries finally agreed on a single Braille code in 1932.

“I don’t remember a time when I couldn’t read Braille,” says Ariel Silverman, author of Just Human: A Search for the Wisdom of Disability, Respect, and Inclusion. “Louis Braille is one of my top three heroes and all-time inspirations. His work was not only for his own benefit, but for the benefit of countless generations of blind and visually impaired people—it was truly unique.”

In 1952, the French government moved Louis Braille’s remains from the modest cemetery in Coupvray to the Pantheon in Paris, home to France’s greatest heroes. (At the request of the people of Coupvray, Braille’s hands remain in a small urn in the village.) At a ceremony marking the 100th anniversary of his death, Helen Keller, the blind American writer, spoke to international dignitaries.

“We blind people owe Louis Braille as much as humanity owes Gutenberg,” Keller said. “The letters we feel under our fingers are the precious seeds from which our intellectual wealth has grown. Without the system of dots, our education would be chaotic and insufficient!”

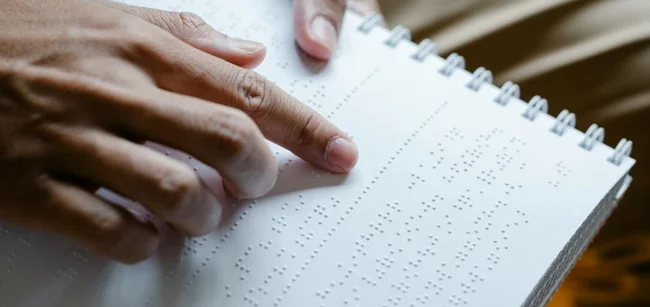

Braille is a method of reading and feeling text by touch. It is used primarily by people with visual impairments, but sighted people can also read Braille. Sighted people may benefit from Braille if they have a family member who is blind or visually impaired. There are many versions of Braille, including musical, mathematical, and several types of literary fonts. Level 2 is the most widely represented and used (consists of the 26 standard letters of the alphabet, punctuation marks, and abbreviations).

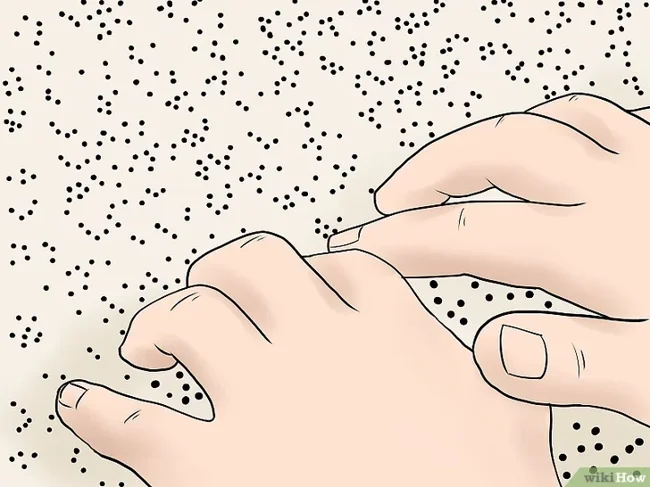

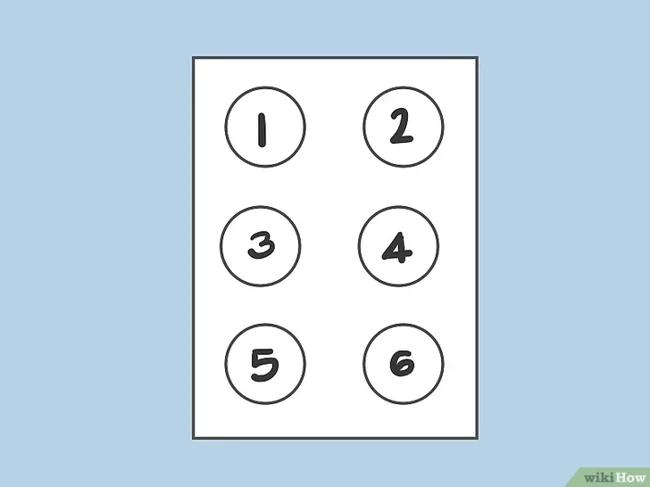

Learn the position of the 6 dots in a cell. Each cell has no meaning, and the meaning varies depending on the version of Braille you are reading. To read, you must know the location of the dots and the spaces. Braille printed for the sighted may have "shadow dots" in the spaces; Braille printed for the blind has no spaces.

Learn the first 10 letters of the alphabet (A-J). These letters only use the top 4 dots. They do not use the bottom two dots.

Learn the next 10 letters (K-T). They are similar to letters A through J, except they also use dot 3.

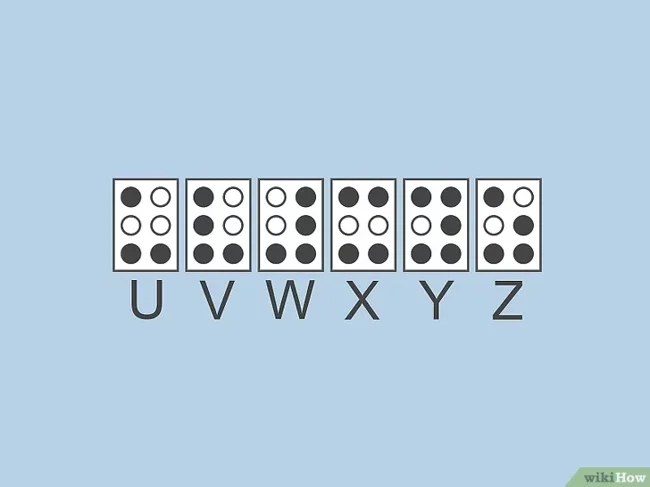

Learn the cells for letters U, V, X, Y, and Z. They are similar to letters A through E, but they also use dots 1, 3, and 6.

The letter W is an exception to the rule. Braille was originally developed in French, which does not have the letter W.

Learn punctuation. Pay special attention to additional signs and symbols (capital and small letters of different alphabets, number sign, etc.).