This Roman quarry once hid smugglers and is now home to rare species of bats.

Beer stone has been a valuable building material since the Roman era. Two thousand years of quarrying have created a winding system of caves that extend deep into the earth near the village of Bir, which gives the stone its name.

Medieval window frames made from beer stone

The first Romans to arrive on the coast of what is now Devon must have noticed the limestone cliffs near the mouth of the River Exe. The Romans quickly realised that the cliffs contained open veins of fine-grained limestone. They began quarrying the stone wherever they could find veins on the surface.

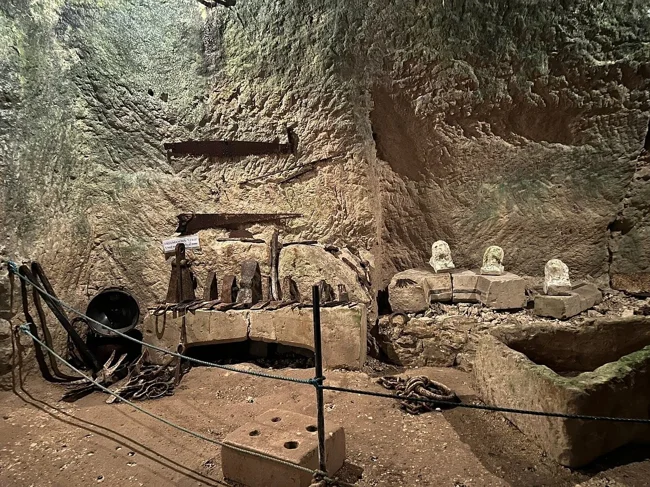

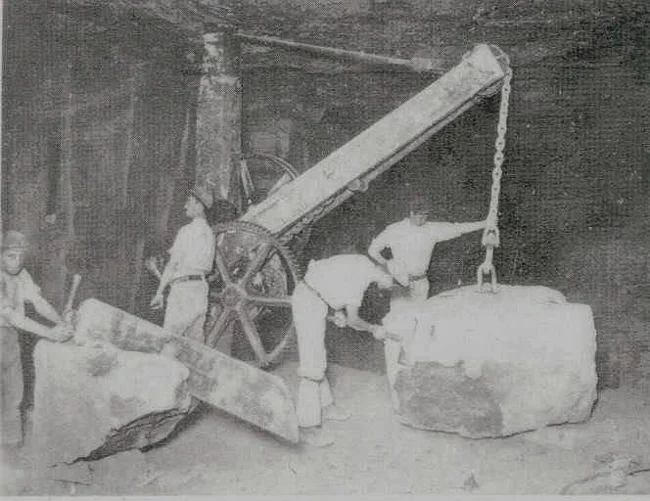

Once all the stone on the surface had been mined, they had to dig deeper to find more, which they dug with picks and wooden wedges.

An exhibition of historical tools at the entrance to the cave

They used the stone to build important public buildings. The stone was taken to the mouth of the river, where it was loaded onto boats for subsequent shipment.

After the Romans left, the Saxons continued to use the quarries. Saxon quarries are easily distinguished by their sharp square corners, unlike the earlier rounded Roman ones.

Beer stone is easy to cut and process, but when exposed to air it hardens and becomes more durable.

Because of the hardening, the stone was often cut on site and then transported and used in the construction of famous buildings such as Windsor Castle, London Bridge, and Westminster Abbey. The stone, known worldwide for its color and texture, was shipped to Missouri for use in the construction of Christ Church Cathedral in St. Louis.

Christ Church Cathedral in St. Louis

The caves are home to more than just a thousand-year-old beer stone. After the Protestant Reformation and subsequent persecution of Catholics, local Catholics began holding secret masses in their murky depths. And in the early 19th century, smugglers, including the infamous Jack Rattenbury, used the vast ancient cave system to smuggle contraband from seagoing vessels.

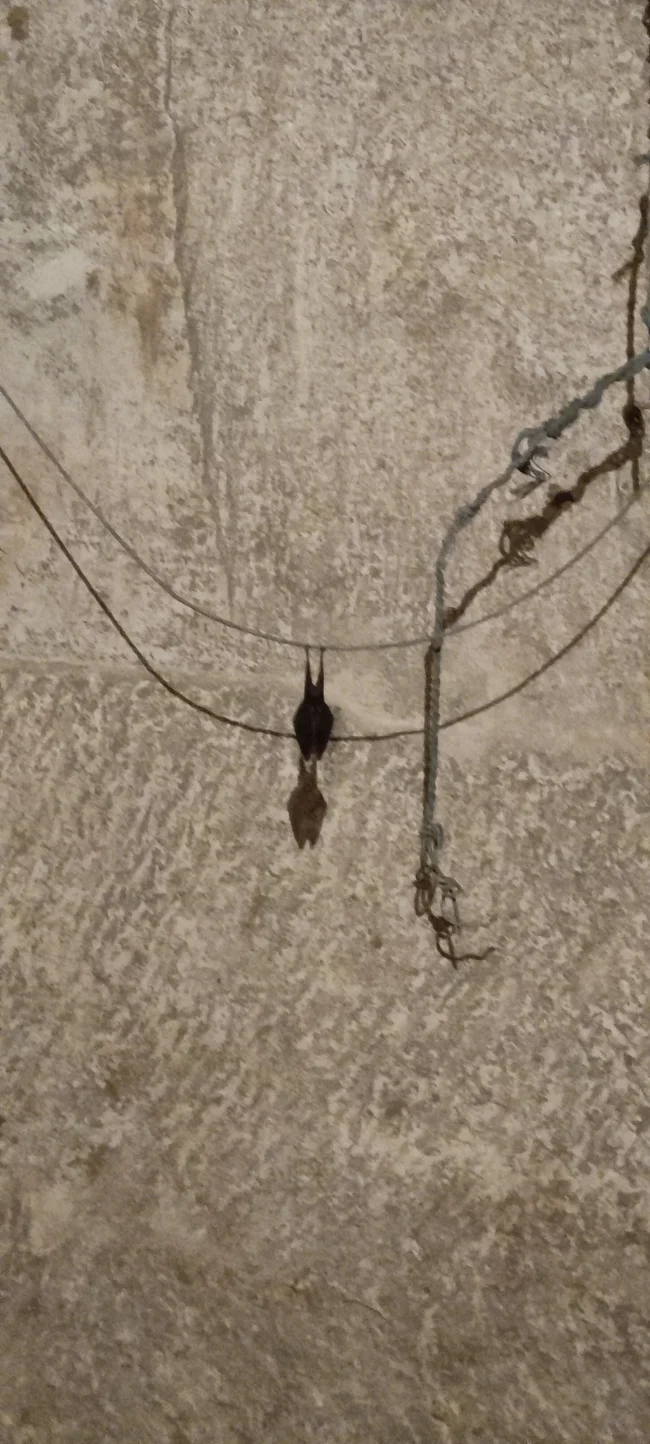

Quarrying of the caves ceased in the early 20th century after a new site was discovered. The site is now of particular scientific interest due to the bats that have chosen the caves as their home. The Greater and Lesser Horseshoe Bats, Daubenton's Bat, Natterer's Bat, Whiskered Bat, and the rare Bechstein's Bat spend the winter inside.

Add your comment

You might be interested in: