Marshalsea – a debtor's prison where life was in full swing behind bars, and debts accumulated faster than on the outside (13 photos)

In the Victorian era, being in debt and unable to pay was considered a serious crime.

Across Britain, special debtors' prisons existed to incarcerate such "financial criminals," accounting for almost half of all the country's penitentiaries.

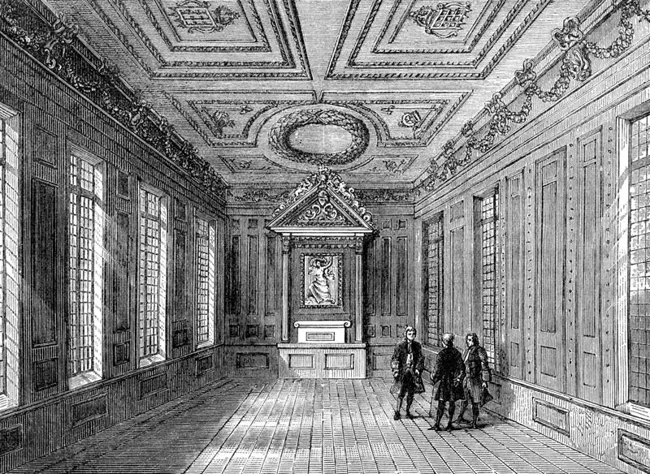

Marshalsea Prison, Southwark, London, 18th century

From the 14th century until the reform of the Debtors' Act of 1869, anyone could be imprisoned for a debt of just 40 shillings (about £278). Unsurprisingly, approximately 10,000 people were imprisoned annually for debt. At that time, only merchants and tradesmen could declare bankruptcy, so the poorest members of the working class were most often imprisoned.

Inside the building

Imprisonment itself was not a punishment. The judge determined the measure of restraint: from execution and flogging to confinement in stocks or the pillory for humiliation and suffering. Prison was merely a place of detention until a debt was paid or a court verdict was reached.

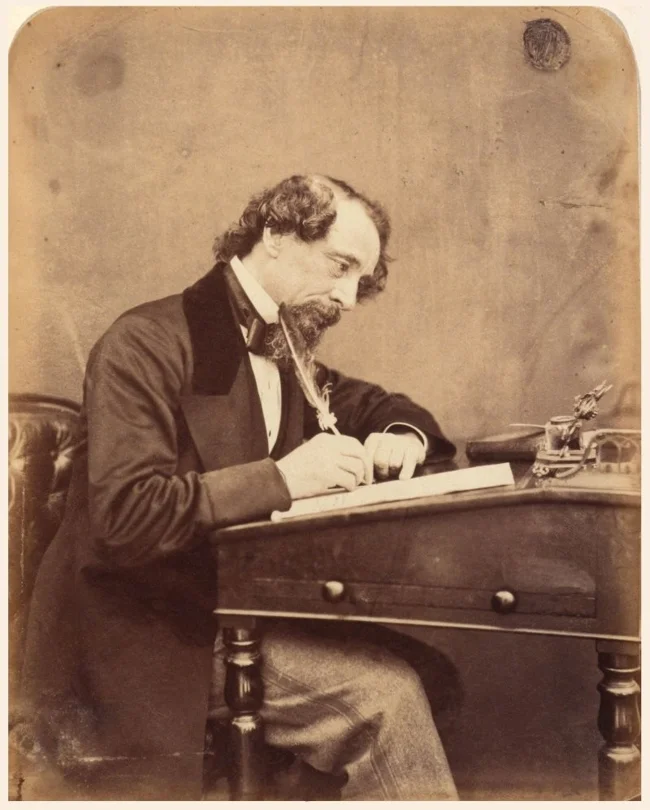

Charles Dickens

These establishments operated as toll-paying inns, run by greedy, often sadistic, keepers. Conditions were appalling, and cruel treatment was commonplace. Prisoners were forced to pay for rooms, food, and even for such mundane tasks as turning a key or removing shackles. Prisons became the perfect system of extortion.

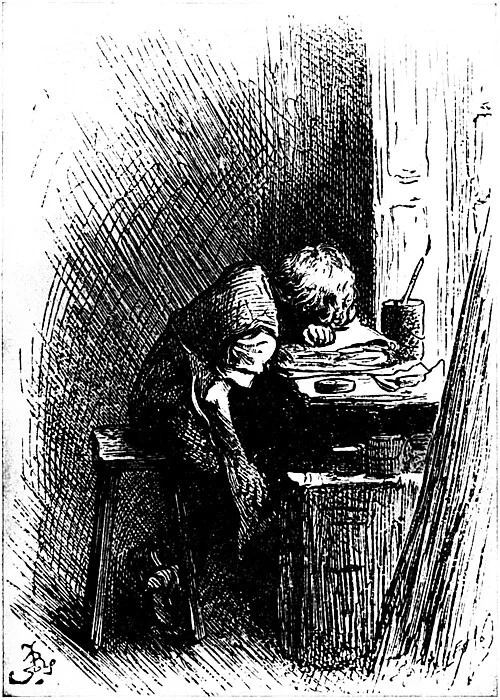

Artistic depiction of Charles Dickens forced to work in a factory after his father was sent to the Marshalsea.

At London's Marshalsea Debtors' Prison, privileged prisoners who could afford it had a bar, a shop, and a restaurant. The rest were crammed into tiny cells. The poorest, unable to afford food, went hungry unless someone gave them alms. However, these alms were often stolen by the jailers. According to a 1729 parliamentary committee report, three hundred prisoners died of starvation in the Marshalsea within three months.

The Marshalsea was the most notorious of all debtors' prisons, particularly thanks to the works of Charles Dickens. His father was sent there in 1824 for a debt to a baker.

Still from the TV series "Little Dorrit" (2008), based on the novel by Charles Dickens.

This event so shocked the writer that he forever became an ardent advocate for prison reform. Dickens described the Marshalsea and other debtors' prisons in several novels: The Pickwick Papers, David Copperfield, and, most extensively, Little Dorrit, in which the protagonist's father ends up in the Marshalsea due to debts so complex that no one can figure out how to free him. The theme of debt and social injustice became a leitmotif of his work.

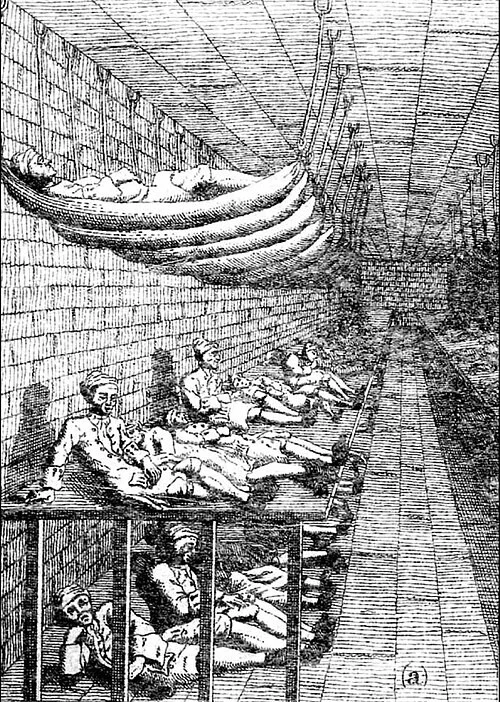

Men's ward in the Marshalsea, Prison Committee, 1729

Escape from prison was extremely difficult for debtors, as new prison fees were added to the original debt. In addition to paying for food and shelter, prisoners were fined for a variety of "crimes": excessive noise, fighting, swearing, smoking, stealing, damaging a staircase, and so on.

Even after paying off the initial debt, a prisoner could remain behind bars because of money owed to the prison itself. When Fleet Prison closed in 1842, two debtors were found there, both serving thirty years.

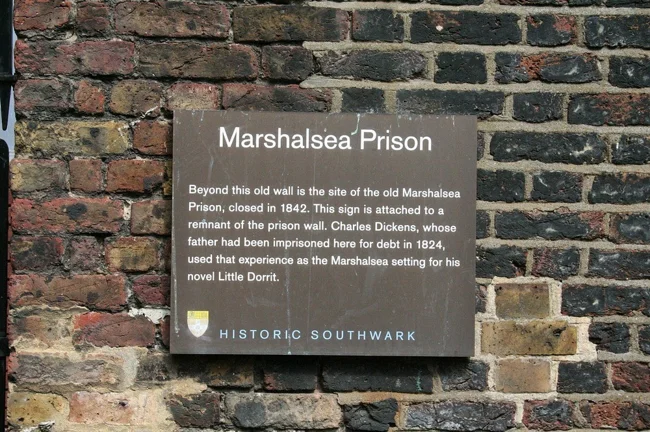

Remains of the wall, 2007

Therefore, prisoners often moved their families into the prison, treating it as a new home. When Dickens's father ended up in the Marshalsea, his wife and younger children moved in with him, while twelve-year-old Charles lived in the flat of a family friend.

Entire communities formed in debtors' prisons. People married, gave birth, and raised children in secret. The term "fleet marriage" even emerged to describe any secret wedding performed outside of church.

Prisoners were usually allowed to work to earn their keep. In 1729, one prisoner ran a coffee shop in the Marshalsea, another a butcher's shop. A tailor and a barber also worked there. Some rooms were used as brothels.

This horrific institution was finally closed by Act of Parliament in 1842. Most of the prison was subsequently demolished, although some of its rooms remained in use as shops and living quarters until the 20th century. A library now stands on the site. All that remains of the Marshalsea is a long brick wall marking its southern boundary.