Landing cost vertebrates the ability to regenerate (2 photos)

The migration of vertebrates from water to the land-air environment was a turning point in the history of the biosphere. However, this evolutionary leap also had serious side effects: it led to the loss of the ability to restore lost body parts in reptiles, birds and mammals.

In a new article, biologists examined the genetic and evolutionary aspects of land development and found that a sharp weakening of regeneration became a kind of “payback” for the adaptation of animals to a different environment.

For most of its history, life on Earth was really just “life in the water.” The situation began to change only at the beginning of the Paleozoic era, when the first primitive plants appeared on land - descendants of green algae, mushrooms and invertebrates like scorpions.

Chordata, or rather animals with a backbone, got to the shore much later, when there was already some company there. The first traces of vertebrates on land were left by “fishapods” like Tiktaalik, a transitional link between fish and amphibians.

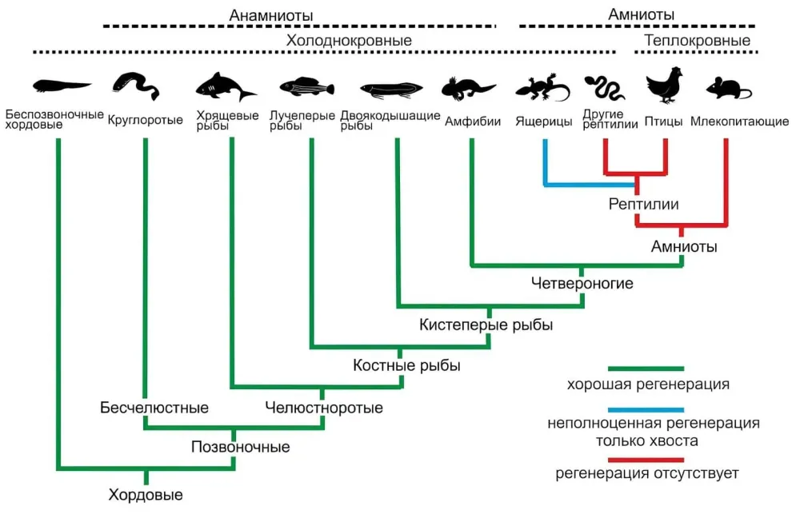

Later, it was vertebrates that became the largest animals in the land-air environment and a key component of its ecosystems. From the pioneer amphibians (or amphibians) came reptiles, and then mammals and birds. However, the dominance of vertebrates on land turned out to be a loss for them: they regenerate much worse than the so-called anamnia (lower vertebrates) and many invertebrates.

Indeed, fish and amphibians easily and quite quickly regrow large parts of their bodies if they are lost - say, if someone bites them off. For example, an axolotl can recover limbs, heart and even brain after amputation.

Reptiles, and even more so birds and mammals, are a completely different matter. There are only a few exceptions, such as lizards, which are capable of tail regeneration after loss, including intentional discarding. The remaining terrestrial vertebrates (amniotes) cannot even regain a lost finger. Their ability to self-heal is limited to healing wounds and “growing” individual organs, such as the liver.

Scientists from the Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Russian National Research Medical University, the authors of a new publication in the journal Biology Reviews, decided to find out how the loss of regenerative abilities is related to a change in living environment. The researchers suggested that they sharply decreased due to the appearance in vertebrates of new characteristics that were more important for the development of land: complication of immunity, keratinization of the skin surface, transition to warm-bloodedness (homeothermy), as well as an increase in body size.

Evolutionary restructuring affected the genomes of animals: they lost many genes and regulatory DNA regions (enhancers) that helped their ancestors. Now such restrictions are recorded in the genomes of higher vertebrates, including humans.

Scientists noted that animals forgot how to restore their bodies much earlier than they lost the genes necessary for this. In total, there are about 150 of these - in fish and amphibians they are needed for the early stage of regeneration, which begins immediately after injury. Unlike genes that are turned on later, early regeneration genes do not affect the embryonic development of the organism, so their removal did not lead to fatal consequences for animals.

It also follows from the new article that the most promising way to restore a limb in a person is to first create its embryonic rudiment. It can be obtained from induced stem cells using tissue engineering. In the future, such a “blank” should grow into a full-fledged arm or leg.