An inexhaustible inheritance, a Nigerian uncle and the story of noble weaning (11 photos)

Surely each of you received an email informing you about a will from an unknown but very rich uncle from Nigeria. Who died safely, but left clear instructions to the executors regarding the inheritance.

It’s easy to receive tens of thousands, and maybe even millions: you just need to transfer a modest fee of a couple of hundred dollars. And you can enjoy the serene life of a millionaire.

It turns out that this scam is not a modern invention. Its history goes back almost 150 years. And it all started with the so-called Spanish prisoners.

The New York Times published an article in 1898 about widespread mail fraud. The article, entitled "An Old Scam Resurrected," details how the "Spanish Prisoner" scam typically begins:

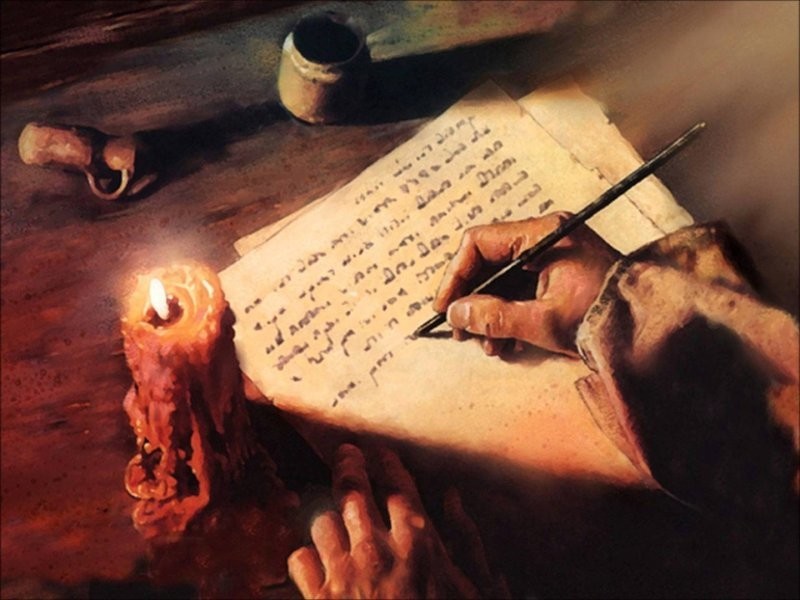

The author is always in prison because of some political crime. He always has a large sum of money hidden, and he invariably wishes that it would be found and used for the care of his young and helpless daughter by some honest man. He knows about the prudence and good character of the recipient of the letter from a mutual friend, whom he does not name for reasons of caution, and turns to him for help in difficult times.

In the 19th century, mail scams were a simple and effective way to illegally take money from wealthy citizens. What did the good Samaritan need when he simply opened the mail on a boring day? The sender of the letter is “ready to give a third of the hidden fortune to the one who returns it.”

What happens next is that in order to return the treasure, the reader must first send some money.

The essence of this scam, for which Nigerian and not-so-uncles are periodically arrested, remains unchanged, with the exception of a few technical details.

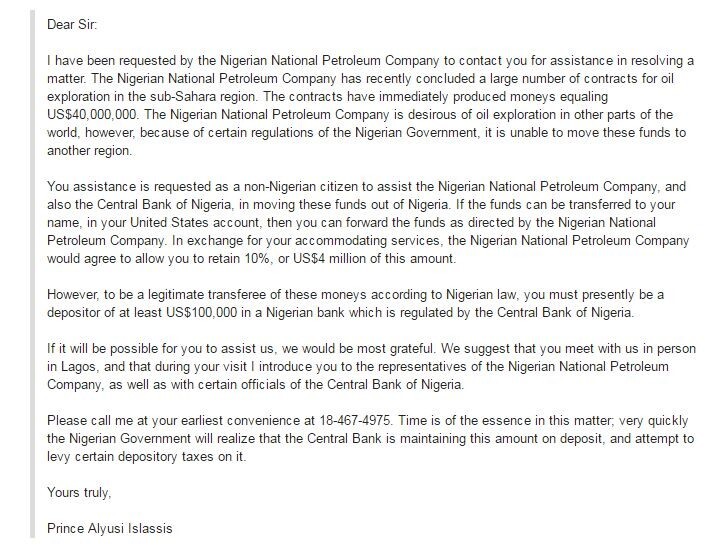

An example of one of the letters

The scam became known under the romantic name "Spanish Prisoner" because the letter's author often claimed to be in a Spanish prison for reasons that arose during the Spanish-American War. “The letter is written on thin blue paper, such as is used for foreign letters, and is written as English is written by fairly educated foreigners, with misspellings and the occasional foreign idiom,” the Times article noted.

As in 1898, today's covert extortions appear real at first glance, but upon closer inspection are not very convincing. The English language is garbled and the official seal of some Nigerian government agency doesn't look quite right. And between the lines there is a silent despair.

Eugene Francois Vidocq

And yet people fall for it. After all, the point of the scam is not that it will work every time or even one time out of a hundred. A scammer only needs a few gullible citizens to make millions. One victim in the US lost $5.6 million to scammers. One arrested Nigerian spammer is rumored to have filled his pockets and accounts with an estimated $60 million.

But even in those days when letters had to be written by hand, this scam was amazingly successful. Eugene Francois Vidocq, who is called the father of criminology, in his memoirs described a version of this fraud committed by prisoners in France at the beginning of the 19th century. This was long before the Spanish-American War, when the scheme was known as the “letters from Jerusalem.”

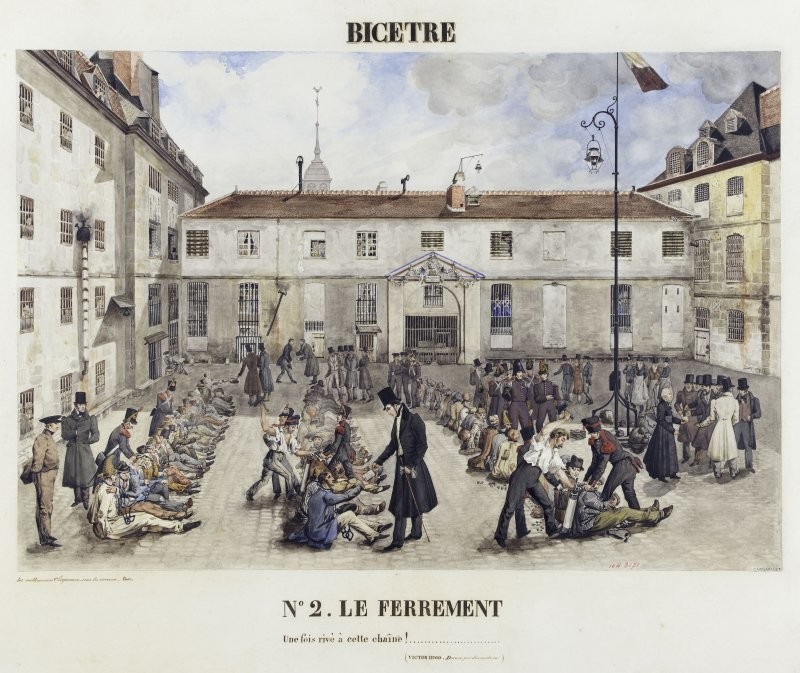

Vidocq, who was himself a criminal before founding the French police force, saw these letters with his own eyes while imprisoned in Bicêtre prison.

“Sir, you will undoubtedly be surprised to receive a letter from a person unknown to you,” began one of these messages. The structure of this letter is elegant: before beginning the story of his grief, the author first offers a seed, a sweet gingerbread - a box containing 16,000 francs in gold and diamonds, which, according to the author, he and his owner were forced to leave behind after they were detained during the journey. Having placed his bets, he continues to write about his expected imprisonment and finally makes a request, which in this case is very subtle: “I want to know if, with your help, I can get the box and some of the money that is in it. Then I can provide for my immediate needs and pay my lawyer, who dictates this to me and assures me that with the help of some presents I can get out of this case.”

Vidocq wrote that 20% of such letters received one answer or another. And in some cases, prisoners earned hundreds of francs from them, which was tacitly permitted by the jailers, who also received their share.

In the 1980s, scammers in Nigeria began sending batches of paper letters to people around the world. They began using faxes in the 1990s and switched to email in the late 1990s.

A few years ago, a “Nigerian prince,” a certain Mike, was arrested, leading dozens of people who sent countless emails around the world, from the United States to India and Romania, using modern technology to realize the full potential of the fraudulent scheme.

The letter options were very different. So, allegedly, members of the Nigerian royal family who suddenly showed financial difficulties or needed cash asked for some money to get out of a sticky situation.

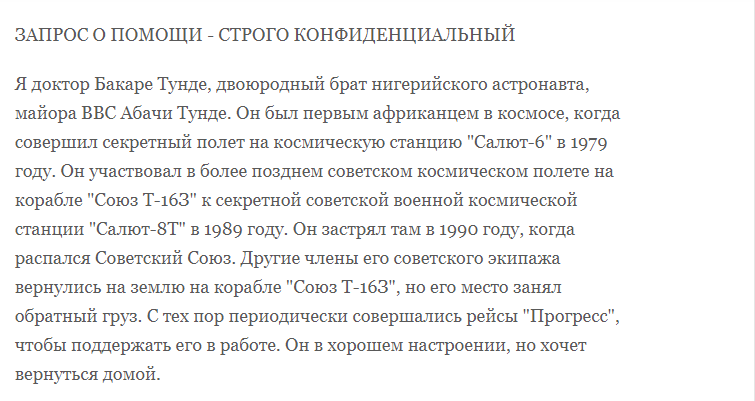

And one absolutely adorable letter asks for a fundraiser for a Nigerian astronaut named Major Abacha Tunde, who has been stuck aboard a secret Soviet space station since 1990 and needs $3 million to pay for his return trip to Earth.

Another hundred years will pass, and perhaps scammers will send holograms, tearfully asking for money and offering fabulous riches in exchange for the same couple of hundred. Believe it or not? Everyone decides for themselves. But not a single gullible or greedy person who tried managed to get rich.