What good are you if you are disabled?

Virginia Hall proved that there is a real sense. And her story became an example of courage, determination, bravery in the face of difficulties and devotion to duty.

In youth

Virginia Hall, a one-legged spymaster, was a woman who overcame enormous odds to become a legendary figure in the world of intelligence.

Virginia was born April 6, 1906 in Baltimore, Maryland. The girl grew up in a wealthy and loving family, which instilled in her a strong sense of independence and determination.

A bright young woman with a gift for languages, she attended Harvard and Columbia University, where she studied French, German and Italian. Plus, she attended George Washington University, where she studied economics.

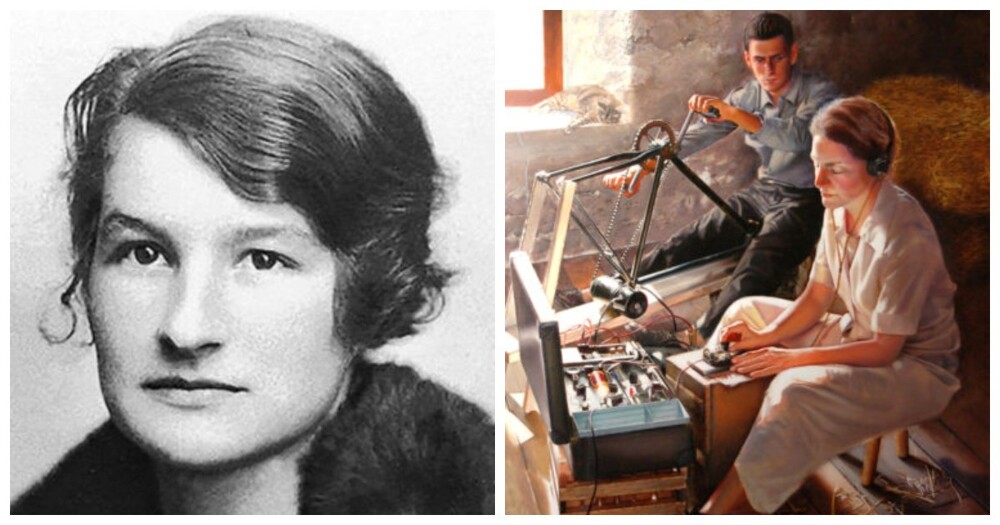

Virginia Hall

She then went to Europe, wanting to complete her education. As a wealthy young American, she traveled the entire continent. After which, in 1931, she received the position of consular clerk at the US Embassy in Warsaw.

A few months later, disaster struck. While hunting, the girl accidentally tripped and shot herself in the left leg.

The wound quickly became infected, and Hall nearly died of gangrene. The difficult decision was made to amputate her leg below the knee. So she became the owner of a wooden prosthesis.

Hall did not like to sit idle for a long time and recovered as quickly as possible. The woman continued to work in Tallinn. But her big dream was to become a diplomat. In principle, women were extremely rarely hired as diplomats, and there was an unspoken rule in the State Department that prohibited the employment of people with disabilities. In 1939, tired of prejudice, Hall quit.

Hall was still in Europe when the first fighting of World War II began. Her thirst for adventure and desire to do the right thing led her to become an ambulance driver for the French army in early 1940.

When France fell to the Nazi war machine in June 1940, Hall went to Spain, a neutral country. Here she met British intelligence officer George Bellows, who changed her life forever.

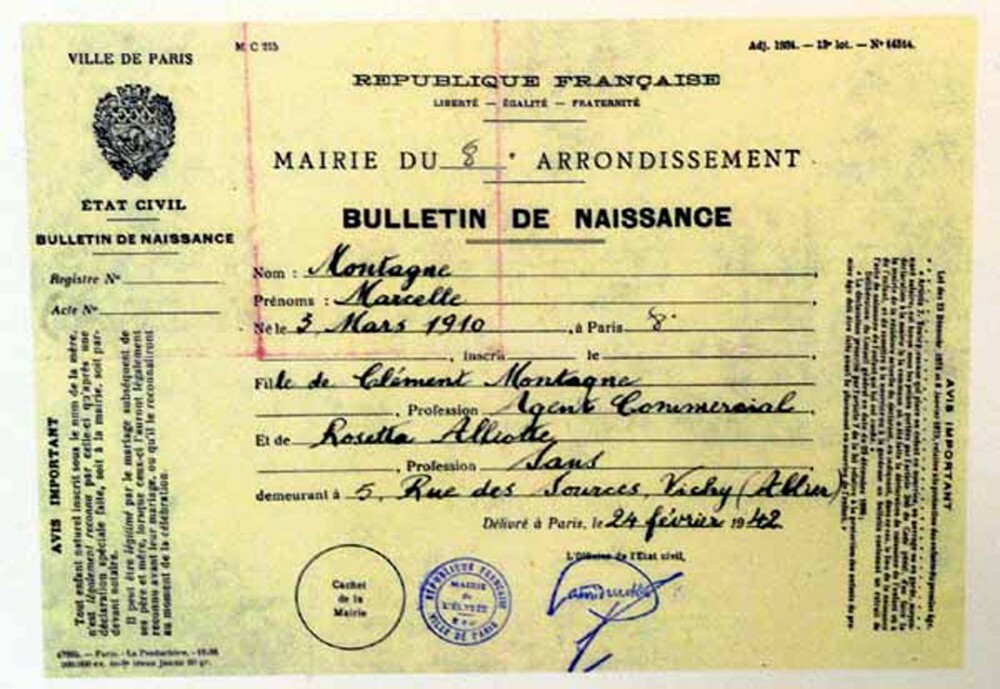

False ID: One of Virginia Hall's fake names was Marcel Montagne.

Impressed by Hall's tenacity, determination, and language skills, Bellows saw something in Hall that the State Department had not. He gave her the phone number of a “friend” who could help her find work in England.

This “friend” turned out to be Nicholas Bodington, a significant figure in the newly created Special Operations Executive (SOE). Thanks to this chance meeting, Virginia Hall came to the attention of an organization that specialized in covert operations and intelligence collection. Her journey into the world of espionage has begun.

Agent Hall

Hall joined the SOE in April 1941 and settled in Lyon in August, posing as a reporter for the New York Post. This cover allowed her to interview people, gather intelligence, and use her stories to hide whatever information she had gathered.

Her achievements were simply extraordinary. Operating behind enemy lines in France, she played a key role in organizing and coordinating resistance efforts against the Nazi occupation.

Hall used her remarkable linguistic talents and intimate knowledge of the French countryside to build an extensive network of contacts. Among them were farmers and shopkeepers, as well as resistance fighters. While stationed in Lyon, she played a key role in helping downed Allied airmen escape France and return home.

Hall also became a skilled radio operator, relaying vital messages to London. But for all this, one of Hall's most impressive achievements was helping to escape from prison 12 agents arrested by French police in October 1941. She recruited the wife of one of the prisoners, Gabi Bloch, to smuggle escape tools into the prison in cans of sardines.

At the same time, Hall organized safe houses, getaway cars and assistants. After escaping on July 15, 1942, the men met Hall in Lyon.

All of this activity attracted unwanted attention from the Nazi occupiers. But despite being pursued by the Gestapo, Virginia Hall managed to evade capture thanks to the resourcefulness and support of the local population.

When the Germans occupied Vichy France, Hall went to Spain. Following her escape, the SOE unfortunately concluded that the agent was compromised and refused to allow her to return to duty for her own safety. In response, she quit working for the British and in 1944 joined the American equivalent of this organization - OSS (Office of Strategic Services).

They sent the intelligence officer to France as an undercover agent, where she spent the next few months dressing up as an old milkmaid, creating intelligence networks and setting up safe houses.

A man's world

Virginia Hall receives an award

In 1947, Hall became one of the first women to join the CIA. Her work there was not pleasant: she constantly faced discrimination, and despite her impressive track record, men constantly passed her over for promotions.

CIA officials later acknowledged this, stating that "she was pushed aside because of her experience, which outshone her male colleagues who felt threatened by her."

The professional spy, even after her retirement, refused to talk about her work with SOE, OSS or the CIA. Which ultimately led to her oblivion. It was only after her death that interest was revived.

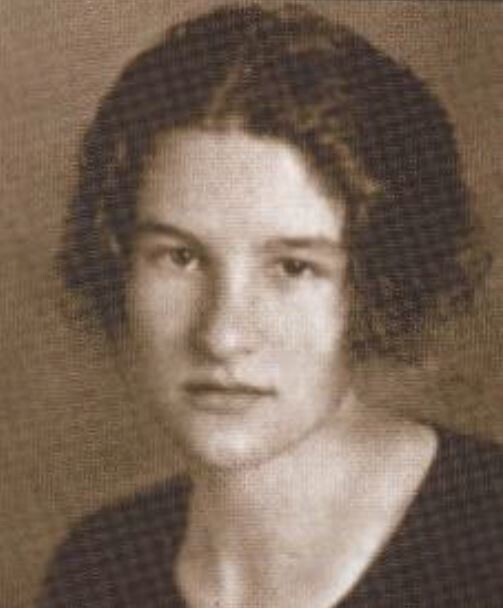

Scene from a theatrical production dedicated to Hall

The story of Virginia Hall is the story of an indomitable spirit. She was distinguished not only by her incredible achievements in espionage, but also by the sincere compassion with which she acted.

In old age

The “Lame Lady” became not just a spy, but also a symbol of hope and resistance during one of the most difficult and sad periods in human history.

Add your comment

You might be interested in: