Astrolabe. Secrets and history of an ancient invention (34 photos)

The astrolabe is one of the oldest astronomical instruments, dating back to Ancient Greece. This ancient instrument was created more than two thousand years ago, when people believed that the Earth was the center of the Universe.

The astrolabe is sometimes called the very first computer. Undoubtedly, this is a device with the deepest mystery and beauty, and we will now try to learn its secrets.

The first astrolabe appeared in Ancient Greece. Vitruvius, in his writing “Ten Books on Architecture,” talking about an astronomical instrument called a “spider,” says that it was “invented by the astronomer Eudoxus, while others say Apollonius.” One of the main parts of this instrument was a drum, where the sky with the zodiac circle was drawn.

Stereographic projection was described in the 2nd century AD. e. Claudius Ptolemy in his work “Planispherium”. However, Ptolemy himself called another instrument “astrolabon” - the armillary sphere.

The final type of astrolabe was developed in the 4th century. n. e. Thus, in Alexandria, almost three hundred years after Ptolemy, the mathematician and philosopher Hypatia was condemned by Christian society for satanic rituals, including, among other things, the use of an astrolabe. She was executed in 415 AD. Her student, Theon of Alexandria, left behind copies of notes on the use of the astrolabe.

After the death of Hypatia and after the fall of the Roman Empire, Europe “lost” the astrolabe. Most ancient Greek knowledge was lost in Western Europe, whose population regarded ancient Greek (and therefore atheist) technology with great suspicion. However, it was carefully guarded by adherents of Islam; their use of the astrolabe is confirmed by many facts. Without Spain and its Islamic religion, the Renaissance would never have come. Most of the ancient Greek texts found have been translated into Arabic. They were later translated into Latin, and the astrolabe was then reintroduced to the vast majority of Europeans.

Scientists of the Islamic East improved the astrolabe and began to use it not only to determine the time and duration of day and night, but also to carry out some mathematical calculations and for astrological predictions. There are many works by medieval Islamic authors about various designs and uses of the astrolabe.

These are the books of al-Khorezmi, al-Astrulabi, az-Zarqali, as-Sijizi, al-Fargani, as-Sufi, al-Biruni, Nasir ad-Din at-Tusi and others.

Since the 12th century, astrolabes became known in Western Europe, where they first used Arabic instruments, and later began to make their own according to Arabic models. In the 16th century they began to be made based on their own calculations in order to be used in European latitudes.

The astrolabe reached its peak of popularity in Europe during the Renaissance, in the 15th-16th centuries; along with the armillary sphere, it was one of the main tools for astronomical education.

Knowledge of astronomy was considered the basis of education, and the ability to use an astrolabe was a matter of prestige and a sign of appropriate education. European craftsmen, like their Arab predecessors, paid great attention to artistic design, so that astrolabes became fashion items and collectibles at royal courts.

It would be pointless to describe exactly how the astrolabe works - it’s best if you see it with your own eyes.

Shuttle-shaped astrolabe.

As al-Biruni wrote, the design of this astrolabe, invented by al-Sijizi, comes “from the conviction of some people that the ordered movement of the Universe belongs to the Earth, and not to the celestial sphere.” The ecliptic and stars are depicted on its tympanum, and the horizon and almucantarata are depicted on the movable part.

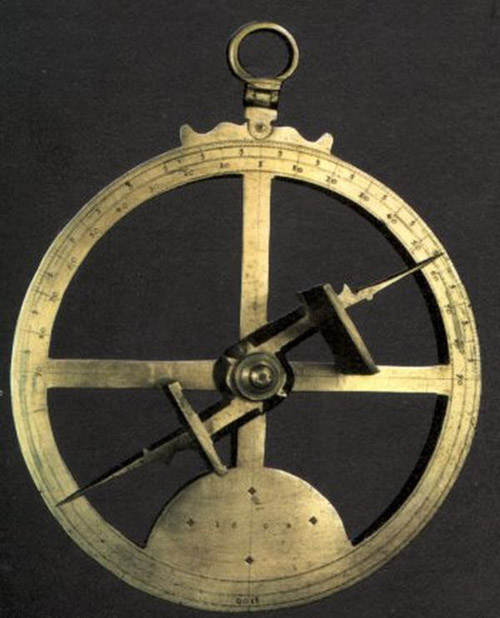

The photo shows an Arabian astrolabe 1090, from the collection of the National Museum of American.

The perfect astrolabe.

In this astrolabe, invented by al-Saghani, the center of projection is not the north pole of the world, but an arbitrary point on the celestial sphere. In this case, the main circles of the sphere are depicted on the tympanum no longer by circles and straight lines, but by circles and conical sections.

Universal astrolabe.

In this astrolabe, invented by al-Zarqali, one of the equinox points is taken as the design center. In this case, the celestial equator and the ecliptic are depicted on the tympanum by straight lines. The tympanum of this astrolabe, unlike the tympanums of ordinary astrolabes, is suitable for any latitude. The functions of the spider of an ordinary astrolabe here are performed by a ruler rotating around the center of the tympanum and called the “moving horizon”.

Spherical astrolabe.

The celestial sphere is represented in this astrolabe as a sphere, and its spider is also spherical.

Observational astrolabe.

This astrolabe is a combination of an armillary sphere and a regular astrolabe, embedded in a ring representing the meridian.

Linear astrolabe.

This astrolabe, invented by Sharaf al-Din al-Tusi, is a rod with several scales, with sighting threads attached to it.

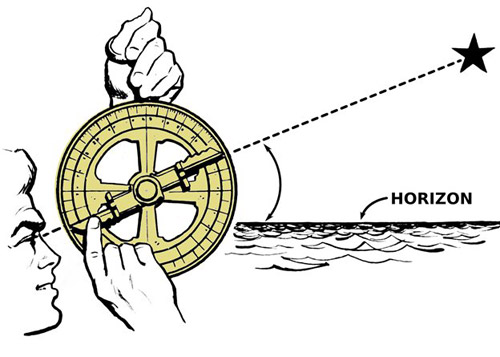

Marine astrolabe.

This device, invented by Portuguese craftsmen at the beginning of the 15th century, is a purely observational device and is not intended for analog calculations.

Marine astrolabe.

Modern encyclopedias say that this device is designed to determine the latitude of a place. In fact, the functions of the astrolabe are much more diverse: it can rightfully be called the computer of a medieval astronomer. Most likely, no one will be able to name the exact number of functions of the astrolabe, since different types of astrolabes could perform different types of work. Back in the 10th century, the Arab scholar al-Sufi wrote a detailed treatise consisting of 386 chapters, in which he listed 1000 ways to use the astrolabe.

Perhaps he exaggerated slightly, but not by much. After all, with the help of this unique tool it was possible:

- recalculate the ecliptic coordinates of stars or the Sun into horizontal ones (i.e. determine their altitudes and azimuths);

- using observations of the stars and the Sun through a special viewfinder, determine the latitude of a place, directions to different cities (mainly to calculate the direction to Mecca), determine the time of day, determine sidereal time;

- determine the moments of sunrise and sunset, i.e. the beginning and end of the day, as well as the moments of star rise, and if there were ephemerides, then of the planets; determine the ascending and setting degrees of the ecliptic, i.e. ascendant and descendant, build horoscope houses;

- determine the latitude of an area by measuring the height of the Sun at noon or the heights of the stars at its climax (I’m not sure if this was done often, since using an astrolabe for this purpose is reminiscent of shooting sparrows from a cannon);

- solve purely earthly problems, such as measuring the depth of a well or the height of an earthly object; and also calculate trigonometric functions (sines, cosines, tangents, cotangents).

- make transformations between three coordinate systems - equatorial (right ascension and declination), ecliptic (longitude, latitude) and horizontal (azimuth, altitude), and much, much more...

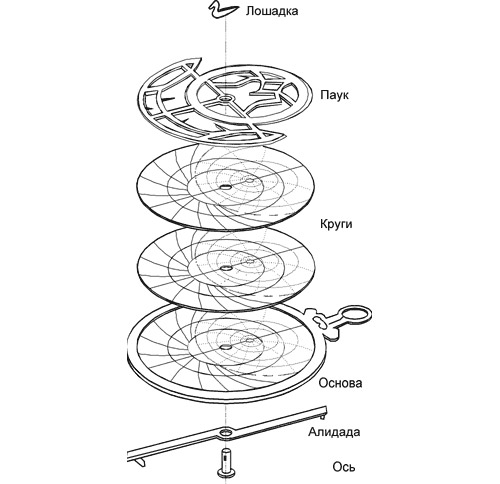

This is how the traditional planispheric astrolabe, usually made of brass, was constructed:

The body most often had a thickness of about 6 mm and a diameter of 15–20 cm (for the largest astrolabes it was up to 50 cm). Although more substantial instruments with a diameter of 30-40 cm were often found, a giant specimen of 85 cm in diameter was known, and, conversely, miniature pocket versions with a diameter of only 8 cm. The fact is that its accuracy directly depended on the size of the astrolabe.

The photo shows an example of how to assemble a simple astrolabe.

In the photo, the Astrolabe by Mahmud ibn Shawka al-Baghdadi 1294-1295 diameter - 96 mm. From the collection of the National Maritime Museum, London

During the heyday of the Arab world, time was measured during the day using a sundial, and at night using a water or sand clock. The astrolabe made it possible to reconcile these watches. To do this, it was necessary to observe the height of the Sun during the day, and at night - one of the bright stars marked on the “spider” of the astrolabe. An interesting device based on the same astrolabe, which can be called a prototype of a mechanical watch, was developed by the famous Arab scientist Al-Biruni. He proposed an astrolabe diagram that automatically showed the relative positions of the Sun and Moon, i.e. lunar phase. The tool had a double body, inside of which gears were fixed. If the outer disk was rotated at a certain speed, the change in lunar phases could be observed in the window. Later, astrolabes appeared, equipped with gears that simulated the movement of planetary spheres. True, at that time there was no reliable mechanical drive, so the device was fully realized only in medieval Europe, when weight and spring drives were invented. And the first mechanical clocks, often installed on the towers of cathedrals in Europe, were made in the form of astrolabes for a long time.

And this is not surprising - after all, complex Arabic astrolabes have turned into real works of art. The star pointers looked not just pins, but spirals and curls in the shape of leaves. The circumference of the instrument was inlaid with precious stones and sometimes trimmed with gold and silver. And all because often a court astrologer would appear with an astrolabe before the menacing eyes of some vizier or shah. An excellent instrument gave weight to the astrologer’s predictions, and not only the fate of the predictor himself depended on this, but also the development of astronomy, more often called then simply the science of the stars.

Pictured is a Persian astrolabe from 1223.

The incident that allegedly happened to Biruni became a legend. One day, an insidious ruler decided to deal with an unwanted scientist and demanded from him an answer to the question: “Which door - northern or southern - will he leave the hall from?” After performing a series of manipulations with the astrolabe, the resourceful Biruni replied that a new door would be cut. The answer turned out to be correct. But more often than not, rulers were generous to their court astrologers, allocating money for the construction of observatories and the creation of all kinds of zijs - ephemeris tables. All this led, albeit to a small extent, to progress in astronomy.

In the photo is a French astrolabe from the late 16th - early 17th centuries.

The modern descendant of the astrolabe is the planisphere - a movable map of the starry sky, used for educational purposes.