Secret Rooms of Faith, or How Priests Were Rescued from Hunters in Medieval England (18 photos + 1 video)

In the English Middle Ages, when power was often held by the sword and conspiracies were commonplace, security architecture became a vital necessity.

Secrets were created everywhere within the walls of castles and family estates: hidden rooms and labyrinths of concealed passages. These hiding places served as the nobility's last chance to escape a sudden siege or treacherous betrayal.

Mary I (Mary Tudor)

However, with the rise of Queen Elizabeth I, the purpose of these hiding places underwent a radical change. Their number began to grow rapidly, not as defensive structures, but as tools of conspiracy, especially in the strongholds of the old Catholic aristocracy, which had fallen into disgrace.

Elizabeth I

The 16th century plunged the country into the abyss of religious wars. The schism between traditional Catholicism and reformed Protestantism divided not only theological doctrines but also states.

In England, this conflict was initiated by Henry VIII, who broke with Rome. His son, Edward VI, deepened the course, introducing stricter Protestant rites. However, his successor, Queen Mary I ("Bloody Mary"), attempted to reverse history by forcibly returning the country to the Catholic Church and unleashing a reign of terror against the reformers.

One of the viewing platforms at Harvington Hall, accessed by tilting a step on the staircase.

The end of this religious game came with the accession of Elizabeth I. Her policy was aimed at building a united, strong state, which also required religious unification. The Church of England was restored—a compromise form that retained the veneer of Catholicism while maintaining Protestant content.

A priest's tunnel on the second floor of Boscobel House in Shropshire

Rome's retaliatory strike was swift: the Pope declared Elizabeth deposed, equating Catholics with traitors. A veritable priest hunt began across the country. Draconian laws were passed: Catholic pastors were banned from entering the country, and harboring them was punishable by confiscation of property, imprisonment, and even death.

At Traquair Castle in Peebles, Scotland, a secret priest's hideout remains on the top floor – a staircase hidden behind a bookcase.

Across England, a vast network of informants and professional detectives operated to track down the perpetrators.

A priest's secret hideout is visible through the floor windows

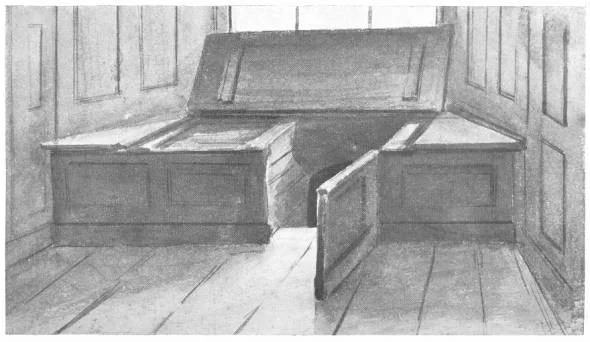

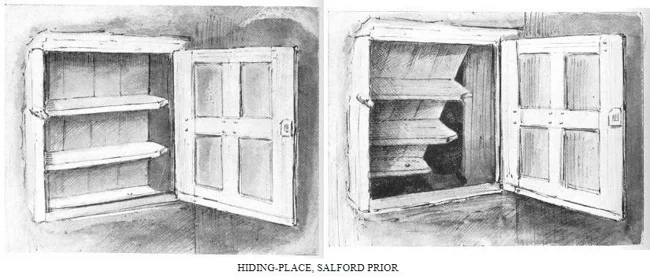

It was under these conditions that the phenomenon of hiding places for persecuted priests arose. Going underground, the clergy hid in the homes of faithful Catholic families under the guise of tutors or distant relatives. To save them, ingenious hiding places were built into the architecture of the houses. They were constructed behind false fireplace mantels, under chapel floors, inside double walls, or within the thickness of stone staircases.

The priest's chamber is located behind the false fireplace in Harvington Hall. It leads to the attic, which has another exit that allowed the priest to escape to another part of the house.

These cells were incredibly cramped. A person could only squat or lie still. Searches could last for days while hunters tapped the walls and measured the rooms. The hidden priest had to exist in pitch darkness, silence, without food or water, risking suffocation or death from exhaustion.

Nicholas Owen, a humble lay Jesuit who dedicated his life to this dangerous craft, became a legend among the creators of these life-saving traps. Possessing an extraordinary mind as a carpenter and engineer, he turned the construction of secret rooms into an art form.

His designs were so masterful that many of them were not discovered during searches and were only uncovered centuries later during restorations. He is also credited with the daring escape of the Jesuit John Gerard from the Tower of London, the most impenetrable prison in the world, in 1597.

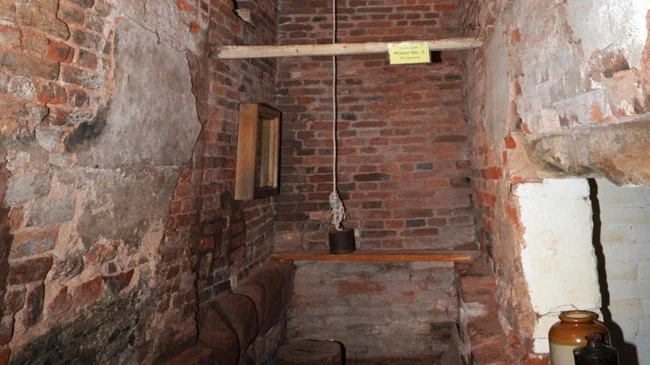

Priest's pit, a former medieval sewer, beneath the kitchen, Baddesley Clinton, Warwickshire

Owen's legacy in stone and wood can still be seen today in ancient English manor houses. These include Sawson Hall in Cambridgeshire, Haddington Court and Harvington Hall in Worcestershire (the latter contains as many as seven such hiding places), and Cawton Hall in Warwickshire.

One of the many clerical chambers built by Nicholas Owen at Harvington Hall

The master's own fate was tragic: in 1606, he voluntarily surrendered to the authorities at Hindlip Hall to divert suspicion from other priests hiding there. Nicholas Owen steadfastly endured terrible torture in the Tower without revealing a single secret and died of his wounds, going down in history as a martyr and genius of the Catholic underground.

Saint Nicholas Owen, Patron Saint of Illusionists

Owen was canonized in 1970 and became the patron saint of escapologists and illusionists.

The priest's chamber at Harvington Hall, above the bakery oven, within the chimney stack

The story of the secret chambers and the heroic deed of Nicholas Owen are more than just an architectural mystery or a chapter in religious conflict. They are a powerful symbol of the human spirit in an era when faith became a battlefield and the home a fortress. Priests' chambers evolved from medieval refuges from civil strife into weapons of a secret war for conscience, in which the Jesuit architect was one of the chief strategists.

Each room hidden behind the paneling was a silent challenge to the state machine, an act of civil disobedience in which the entire family participated, from the aristocratic master to the last servant who hid a terrible secret. The hunt for priests revealed a paradox: by attempting to eradicate papism, the authorities unwittingly made Catholicism even more attractive, effectively a faith of martyrs and the underground, purged of worldly wealth and politics.

Nicholas Owen, who died in the Tower of London, created more than ingenious shelters. He built an architecture of resistance, a fragile yet incredibly strong network that preserved the living fabric of English Catholicism for decades.

His rooms, discovered centuries later, are silent witnesses to the lengths people will go to defend not only the lives of others, but also the right to a different thought, a different prayer, a different truth.