What happened to the mass sterilization program in India (7 photos)

Since 1969, Indian authorities have been annually urging the population to limit births under the slogan "Two of us, two of us." Each family is recommended to have no more than two children.

In the early 1960s, there were at least six children per adult Indian woman; today, only five regions in India have more than two children per family. Since the mid-20th century, the primary method of birth control has been sterilization, most often forced. Why did the authorities decide to take this step, and what were the consequences?

In the early to mid-20th century, every woman tried to have as many children as possible, with only boys being valued as breadwinners. Mortality from epidemics, natural disasters, and even famine was high, and there was no pension system, so having many children was considered the best strategy: there was a greater chance that one of the surviving children would be able to support elderly parents. However, the government had a completely different vision: the population was growing, and a large family in India was usually extremely poor.

Discussions about the use of contraception were already underway at the highest levels even before the country's independence. However, Mahatma Gandhi opposed the use of condoms: they were supposedly harmful, and therefore one simply needed to fight lust by improving oneself.

Indian physician Raghunath Karve advocated family planning, suggesting that instead of torturing people by forcing them to renounce their natural desires, he instead used progressive Western contraception. South Indian reformer Periyar generally believed that Gandhi's methods were violence against women, who could choose for themselves whether to have children.

After independence, Western-educated politicians came to power in India and disbelieved in Gandhi's "self-improvement." In 1951, a family planning program was introduced in India. This included propaganda, as well as state-funded and voluntary medical services such as female sterilization and vasectomy for men.

Mass female sterilization in India led to numerous deaths

The government thought that if the birth rate was low, the country would become rich, like in the West. However, this logic didn't work in India: Indians continued to procreate, hoping that at least one child would be able to get an education and get ahead. It soon became clear that there was insufficient funding for the grandiose project, and Western powers were offering little assistance, as they had plenty of problems of their own.

In 1968, Stanford University entomologist Professor Paul Ehrlich wrote a book arguing that the world's population was growing rapidly, meaning there wouldn't be enough food for everyone. He convinced the public that 65 million Americans and all of Great Britain were at risk of starving to death.

According to Ehrlich's calculations, by 1951, India alone had a population of 361 million people, producing at least 500,000 children annually. By 1965, India was on the brink of famine and begging for aid. However, US President Lyndon Johnson agreed to provide aid, but only if the Indian government took the most drastic measures to reduce the birth rate. Unconditional aid was also provided: from the Rockefeller Foundation, the UN, the World Bank, and other organizations, but it was insufficient.

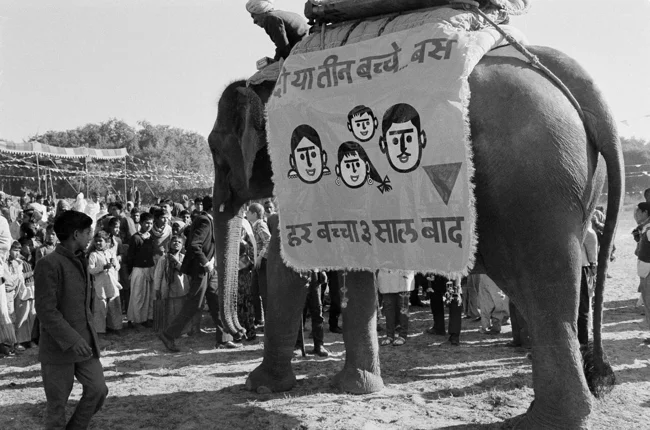

An elephant adorned with a propaganda poster urging a maximum of two or three children, 1969

Propaganda like "fewer children, more food for everyone" didn't work on the ignorant masses. Then, Indian state authorities began setting up "sterilization camps," where they held celebrations with public festivities and food distributions. Vasectomies were performed there, in the field. In 1971, over a million men were sterilized; by 1973,

— up to three million. Those who voluntarily agreed to the operation were given money and valuable gifts like tape recorders and household items.

But even this wasn't enough. By 1975, following a drought, inflation had set in and food prices had skyrocketed. Nationalists and opposition figures turned against Indira Gandhi, while her son Sanjay was ordered to take emergency measures to combat the high birth rate. Today, these measures are perceived as "a fight against one's own people." Police seized villages, evacuating people by the busload and truckloads, sending them for forced sterilization. Over the next two years, more than 6.2 million men, including those who had not yet had children, were sterilized.

In 1977, Indira Gandhi suffered an election defeat: the people, predominantly men, resented the sterilization issue. To regain power, Indira shifted the focus of family planning to a less politically active segment of the population—women.

Female sterilization, which involved tubal ligation, was also sometimes performed in unsanitary conditions and without anesthesia. The exact number of women undergoing the procedure is unknown, but the mortality rate from this invasive procedure was high. Plans were made to sterilize at least 30 million women and insert IUDs into more than 25 million by 1990. Those who volunteered were given small monetary rewards.

In 2013-2014, 4.6 million sterilizations of both sexes were performed in India. Some were fatal.

What was the outcome and what were the consequences? Today, India has a population of over 1.46 billion, meaning Gandhi's campaign has failed. Sterilization remains the primary method of contraception in India. Meanwhile, in his annual addresses to the nation, Prime Minister Narendra Modi frequently mentions that reducing the birth rate is the responsibility of each citizen, and that citizens planning their families are expressing patriotism and love for their homeland. International experts, however, believe that Indians will only achieve a level of education sufficient for a conscious demographic transition by the 2060s.