Behind the scenes of the bloody arena: the truth about gladiatorial combat (13 photos)

When we hear the word "gladiator," our imagination conjures up images of a half-naked hero fighting on the sand to the cheers of the crowd. But the reality was more complex, bloodier, and perhaps more interesting. This wasn't just a massacre, but a carefully orchestrated mass spectacle with its own rules, fashions, and harsh laws...

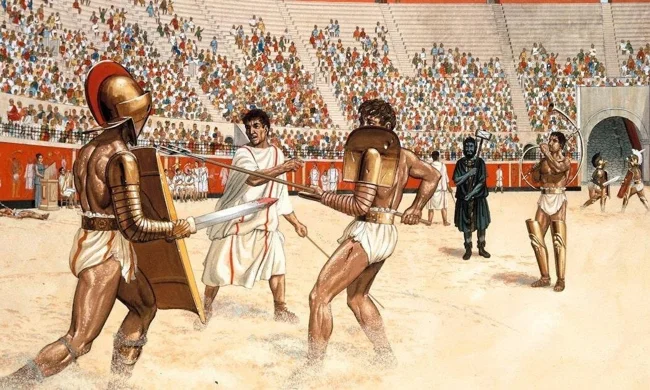

Contrary to Hollywood depictions, gladiatorial combat wasn't a chaotic slaughter. It followed strict rules. The bout was overseen by a lanista (the organizer and owner of the gladiators) and referees. The fight began with a ceremonial procession and a greeting to the emperor or the organizer of the games with the famous phrase: "Ave, Imperator, morituri te salutant!" ("Hail, Emperor, those who are about to die salute you!").

The fights were paired, and gladiators rarely fought to the death. Each fighter commanded a huge sum of money, and their death was a loss to the lanista. If one of the fighters was wounded, he could raise a finger, begging for mercy. The decision of life and death rested with the organizer of the games, who addressed the crowd.

The famous "thumbs down" gesture (pollice verso), which signified death, is most likely a myth. Historians believe that the "putting the thumb in the fist" gesture (pollice compresso) could have signified mercy, while a downward-pointing sword or an extended thumb (symbolizing a naked blade) signified execution.

Gladiators were not a homogeneous mass. They were divided into types, each with unique weapons, armor, and tactics that mimicked the fighting style of Rome's enemies. This "specialization" made combat spectacular and strategic, reminiscent of chess, where each type had its own strengths and weaknesses against the other.

Murmillo: "Fish." His helmet was adorned with a fish-shaped crest. He was protected by arm and leg armor and fought with a large rectangular shield and a gladius sword.

Thracian (Thraex): A lightly armed fighter with a small curved sword and a small square shield. His helmet was often adorned with a griffin, the symbol of the goddess of vengeance, Nemesis.

Secutor: "Pursuer." Specifically designed for combat with the retiarius. His smooth, streamlined helmet, without protrusions, prevented the retiarius's net from snagging.

Retiarius: The most authentic type. He fought nearly naked, armed only with a trident, net, and dagger. His tactics resembled those of a fisherman: entangle the enemy in the net and finish him off with the trident.

Hoplomachus: equipped like a Greek hoplite, with a spear, a small round shield, and a crested helmet.

There were several ways to become a gladiator. Captivity was the most common. Prisoners of war captured in Rome's countless wars were often sent to gladiatorial schools. Slaves who had misbehaved or shown rebelliousness could also be sold to the school.

Surprisingly, many free citizens and even aristocrats voluntarily became gladiators. They were lured by money, fame, and admirers. A successful gladiator was a true sex symbol of his era, his face adorning amphoras and frescoes.

Life in the gladiatorial school (ludus) was harsh and strictly regulated. Fighters were trained, fed a special diet (rich in carbohydrates to build muscle mass, the famous "gladiator's porridge"), and were under constant medical supervision.

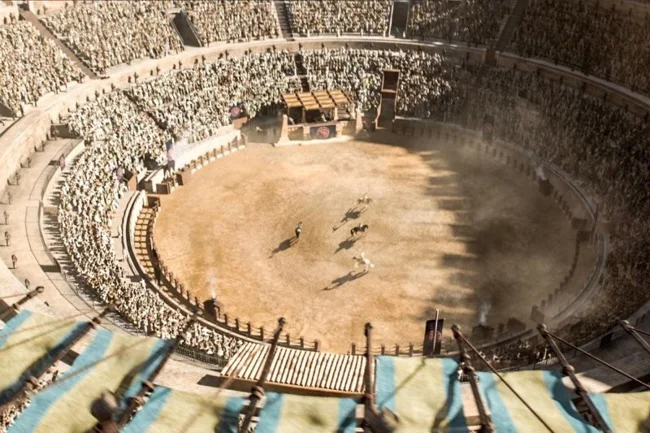

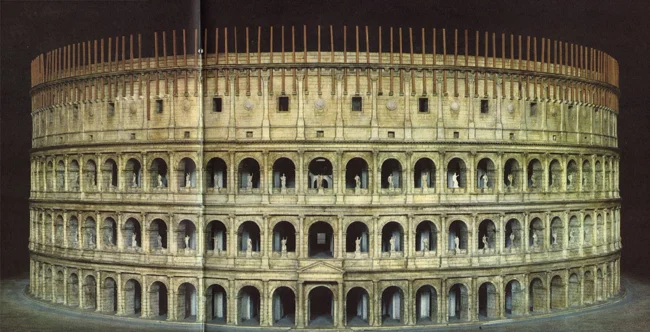

The games were held in forums and circuses, but they truly flourished in specialized structures—amphitheaters. The greatest of these is the Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater) in Rome.

It was a technological masterpiece. It could accommodate up to 50,000 spectators, and its complex system of basements (hypogeum) with elevators and mechanisms allowed for the raising of sets, wild animals, and fighters into the arena, creating stunning special effects. The arena could even be filled with water to stage naval battles—naumachiae.

The popularity of gladiatorial games rested on three pillars. First, the games were a powerful propaganda tool. By staging grand spectacles, the emperor demonstrated his generosity and concern for the people. Second, they were a way to gain popularity and distract the plebs from social problems ("bread and circuses").

The fights were also an object lesson in Roman virtues: courage, fortitude in the face of death, and military prowess. A gladiator who met death with dignity commanded respect. For the average Roman, it was football, boxing, and reality TV all rolled into one. The excitement, the blood, the glory—all of it evoked a powerful emotional response.

The ban on gladiatorial combat did not come suddenly and for more than one reason. Maintaining gladiatorial schools and large-scale games became an unbearable burden for the weakened Empire. Moreover, with the spread of the new religion preaching mercy and the sanctity of life, bloody spectacles began to be perceived as barbaric. Christian emperors increasingly restricted the games.

Gradually, the public began to lose interest in complex combat techniques, preferring the more spectacular and brutal baiting of wild animals or mass executions. Emperor Honorius formally banned gladiatorial combat in 404 CE, although its aftereffects continued for some time.

Gladiator combat was not just a sport, but a complex social phenomenon. It was a fusion of cruelty and ritual, slavery and glory, politics and popular culture. They reflected the very essence of Ancient Rome—great, powerful, and ruthless, where one man's life was a bargaining chip in a grand game of power and spectacle...