A new study challenges the "simple" explanation for Martian organic matter, which, according to the most common hypothesis, was brought to the Red Planet by meteorites.

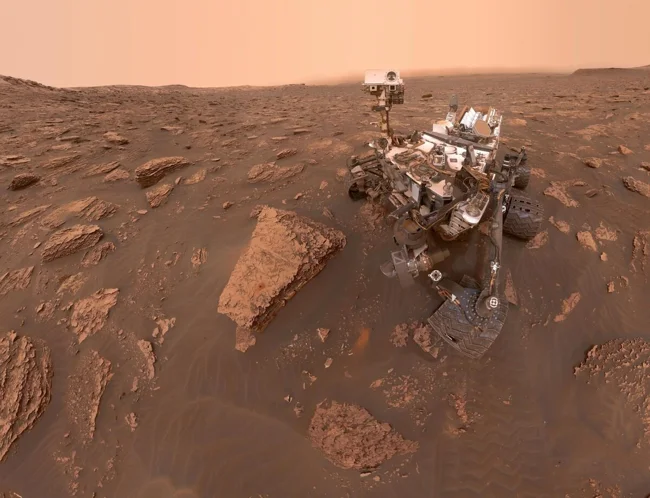

A self-portrait taken by the NASA Curiosity rover on June 15, 2018, when a global dust storm significantly reduced light levels and visibility in the Gale Crater area.

Scientists analyzed organic compounds found by the NASA Curiosity rover and concluded that purely non-biological processes could not have produced the levels of organic matter found in the rocks of Gale Crater.

It all began in March 2025, when the Curiosity team reported the discovery of small amounts of decane, undecane, and dodecane—hydrocarbons with chains of 10–12 carbon atoms, the largest organic molecules detected on Mars at that time.

It was hypothesized that these compounds may be the breakdown products of fatty acids preserved in ancient mudstone (clay shale) in the area of the former lake that was once Gale Crater.

The problem is that it's impossible to determine the exact origin of these molecules from rover data alone. On Earth, fatty acids are typically associated with life (for example, in cell membranes), but it's also known that some complex organics can be "assembled" abiotically—during geological activity or delivered ready-made aboard meteorites.

The authors of the new study then took the next step: they began to consider realistic non-biological sources and estimate how much organic matter they could have produced under similar conditions, given the high background radiation levels on the Martian surface, which is responsible for the destruction of organic matter. The scientists used laboratory experiments, mathematical modeling, and a reanalysis of Curiosity data to estimate the amount of organic matter that should have been present in the rock before destruction—they essentially "rewound" the data back tens of millions of years.

The resulting estimate was much higher than typical non-biological scenarios are capable of. Hence, the cautious conclusion: abiotic processes cannot explain the detected amount of organic matter, so it is entirely reasonable to assume a biological source.

It's important to understand that this isn't irrefutable proof of life on Mars. The study's authors note that additional data is needed before drawing firm conclusions. But the situation is becoming extremely interesting: for the first time, conventional non-biological explanations are insufficient. If new data confirms current findings, we will have one of the strongest arguments yet that life once existed on the Red Planet (or perhaps still exists).

Add your comment

You might be interested in: