Why don't animals catch human diseases and vice versa? (9 photos)

You all know those people who yell at everyone, "Ugh, don't touch that dog, it's full of viruses!" Well, after reading this article, you can respond quickly, clearly, and reasonably. Dogs may have viruses, but humans won't get them, even if you cuddle them 24/7. And the opposite is true: an owner with a cold isn't at all dangerous to their pets. That's because this system is much more complex and interesting than it seems.

When the bowl has been empty for an hour.

But first, let's figure out what this "virus" even is. Many people imagine it as a tiny, evil parasite, eager to infect someone. However, this is fundamentally wrong. A virus isn't even a living creature in the traditional sense. It has no body or metabolism, and it can't move or feed on its own. It's simply a flash drive with a fragment of genetic information that uses the cells of other living things to reproduce itself.

I did everything I could. The host can't be saved... She's addicted to TikTok.

Then a logical question arises: if the virus is so simple and practically lifeless, why would it infect anyone at all? No reason. Viruses don't need anything at all. They don't care about our quarantines, masks, or QR codes at restaurant entrances. They don't intentionally make us sick, because that's how nasty they are. This creepy-crawly thing doesn't even deliberately seek out a person or a dog: it enters someone's body completely by accident: through microdroplets of water, dust, or the secretions of an infected person.

90% of the country's population in the fall and spring.

But now comes the most interesting part, and this will answer the question of the whole article: why don't dogs get our viral diseases, and why don't we get theirs? When a virus enters the body, at first it simply floats in biological fluids. It has no flagella or cilia to swim anywhere. There are also no sensory organs that would indicate the direction of influenza viruses to the nasopharynx, or intestinal viruses to the gastrointestinal tract. This infection simply tries to penetrate ANY cell it encounters!

The virus tries to penetrate a cell. Photo in color.

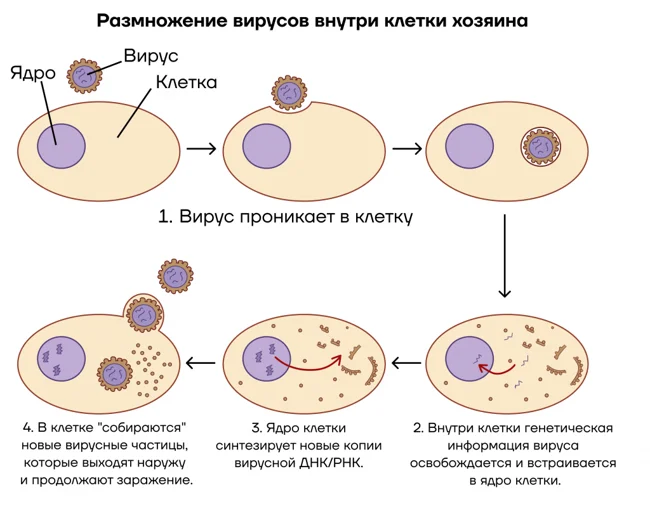

All cells in our body have a membrane containing receptors. They help cells communicate with each other, receive nutrition, and eliminate metabolic waste. They act like locked doors, preventing anything unnecessary from getting in or out. Viruses also have receptors—they poke them into every cell in sight, just for luck. Sometimes they get lucky, and the receptor key on the virus matches the receptor door on the cell. When this happens, the cell itself drags the virus inside, assuming that a receptor match means it's something useful. Having entered the host cell, the virus slips its fragment of genetic information into it, like instructions for action. Instead of going about its business, the host cell endlessly expends its resources on creating new copies of the virus that has entered it. Over time, these copies exit the cell, reenter the body, and the cycle repeats. In other words, the virus doesn't even replicate itself; it simply tricks the cell and forces it to become its own personal factory.

Visual diagram: how a virus infects a cell.

This diagram has a ton of weaknesses, which is why we don't get infected by everything that flies in the air around us. First, a virus needs a specific receptor to enter a cell. Over millions of years of mutations, breakdowns, and reassemblies, some viruses have acquired receptor locks, but they only work for specific cells. Therefore, even if a sick dog or cat sneezes on us, its viruses still won't be able to unlock our cells, and nothing will happen.

I can infect you with just my charm!

Secondly, even if the key and lock match, a surprise awaits inside the virus cell. Due to their extreme simplicity, they require specific environmental conditions: temperature, acidity, and the presence of certain substances. Even within the same organism, these parameters vary among different cells, not to mention cells of different species. And if the right conditions aren't present, the infection will simply disintegrate and disappear as if nothing had happened.

Humans go into bed when they're sick. Cats are always on bed rest!

But once a year, even a stick can shoot. Sometimes, a virus that enters a cell mutates, breaks down, and assembles incorrectly, but very fortunately for the virus. The chances of this happening are extremely low, but sometimes animal viruses can "learn" to infect humans, and vice versa. This is how flu viruses work, for example—swine, bird, and human influenza viruses can periodically mutate and jump from one species to another. Coronaviruses, which affect not only us but also camels, cats, minks, and bats, are also included—remember the case in 2019.

It's infuriating that now we have to check every bat just to have a decent breakfast.

Smallpox and herpes viruses also sometimes change hosts; each has its own specific methods of reproduction and infection, but host change is a fact. And the most important example is the rabies virus. This killer doesn't care at all what the animal is like; all mammals without vaccination are at risk.

Pigs are often intermediate carriers of viruses between other animals and humans, as their bodies are very similar to ours.

So, not all viruses can jump from humans to animals and vice versa; you can cuddle sneezing dogs as much as you like. However, there is also a certain, relatively small group of viruses that live in multiple hosts simultaneously. However, they have been studied, and vaccines and treatments have been developed for many.