"If we die, we want people to accept it as a given. We're in a risky business, and we hope that if something happens to us, the program won't be delayed. The conquest of space is worth risking our lives for."

— Astronaut Gus Grissom, 1965

By the turn of the millennium, the shock of the Challenger shuttle's destruction on live television had faded: more than 15 years had passed, the spacecraft had completed dozens of successful missions, and the flaw that led to the shuttle's 1986 destruction had been corrected. But suddenly, news breaks of another shuttle disaster—this time during landing, not takeoff. The story seems remarkably similar: more talk along the lines of "we didn't know," even though everything was very well known, and promises to fix the flaw for future launches. Today, we remember the Columbia disaster—the first shuttle built, which failed to return to Earth in 2003 at the conclusion of its 28th mission.

Oddly enough, the shuttle wasn't named after the county of the same name in the United States. In fact, that name belonged to a sailing ship used in the late 17th century to explore the western lands of what is now the United States. The shuttle first flew into space in 1981. This was an incredible risk for NASA in general and the astronauts on board in particular. The fact is, spacecraft launches were usually preceded by electronically controlled test runs. In the case of the shuttle, this was impossible due to a number of technical issues—Columbia, like other shuttles in the Space Shuttle program, could only land with pilots in the cockpit.

Of course, all the systems had been tested numerous times before, but only in atmospheric conditions and on the test Enterprise (the name was borrowed from the ship from Star Trek). The crew of the debut mission, STS-1, consisted of just two people: John Young, who walked on the Moon in 1972, and Robert Crippen. After its maiden flight, Columbia completed 26 more missions, and in early 2003, the ship was ready for its next mission, STS-107.

Cold weather was one of the factors that contributed to the Challenger crash, but since then, the design flaw in the solid rocket boosters has been corrected, the shuttle has carried out successful missions for many years, and no other potential hazards have been discovered. Or rather, they preferred not to talk about them.

The investigation into the Challenger disaster revealed that during several missions, other shuttles had been close to destruction due to a flaw common to all four spacecraft (Endeavor wasn't originally planned, being built specifically to replace Challenger), but the problem was ignored. The Columbia crash, 17 years later, will show that this wasn't the only warning sign NASA chose to ignore.

The 28th Columbia mission had a crew of seven, four of whom were on their first flight. On January 16, the shuttle launched into orbit. During takeoff, a piece of thermal protection broke loose from the main tank's mount, striking the edge of the left wing. The incident was not lost on the specialists monitoring the shuttle's launch. However, you don't need to be an expert to see this: if you look closely at the nose of the spacecraft, you can see an object flying off, striking the wing with great force, and then disintegrating.

Thermal insulation is designed to prevent ice from forming on the mounting elements. It is quite lightweight and, it would seem, would not damage the spacecraft, which is built from ultra-strong materials. Moreover, similar incidents have occurred before, but they were limited to minor damage to the shuttle's hull.

For example, a few months before the last Columbia mission, a similar situation was recorded during the Atlantis launch: a piece of the skin fell onto the booster's mount to the fuel tank, causing damage. The report stated that this did not threaten the safe operation of the shuttles. As with Challenger, similar incidents convinced those responsible that the problem was minor.

A week before landing, the crew was finally informed about the heat shield fragment that had struck the wing. NASA's letter stated that nothing serious had happened. Apparently, the crew was simply informed so they wouldn't be surprised by questions from the press upon return to Earth. NASA did indeed believe that the damage to the spacecraft, if any, was minor. On February 1, the Columbia crew prepared for the end of the mission—all they had to do was reenter the atmosphere and land the shuttle on the runway at the Kennedy Space Center.

Approximately 16 minutes before the planned touchdown, the temperature of the left wing began to rise. This is normal during reentry, but the temperature was significantly higher than usual. Then, due to the heating of the left wing, problems began to arise: first, the hydraulics failed, then the tire pressure sensors failed. NASA stated that they were investigating the telemetry data. Commander Richard Husband managed to say, "Roger that, but..." At that moment, the connection was lost, and the spacecraft began to disintegrate. The time was 8:59 AM.

An eyewitness captured the Columbia crash on video. The shuttle began to disintegrate on the left side, then broke into several pieces. The problems arose at an altitude of over 60 kilometers, and debris was scattered over a large distance. The crew had no chance of survival. NASA was still attempting to contact Columbia when breaking news broadcasts of falling fragments of the spacecraft were already airing on television.

During the search operation, approximately 84,000 shuttle components were recovered—roughly 40% of the entire spacecraft. The shuttles weren't equipped with black boxes, but the investigation committee was, arguably, lucky. Columbia carried the Orbiter EXperiments data recorder, which was used to test and configure the spacecraft during its first launches, and it hadn't been removed from the shuttle since.

The investigation committee quickly suspected that the problems were caused by a thermal shield striking the wing. The launch recording, which showed a strong impact of a component on the wing edge, and a problem with sensors in various systems in the left wing during landing, clearly indicated that the cause of the crash lay there.

NASA was reluctant to admit that they knew about the problem immediately after the spacecraft's launch, but did nothing to examine the wing skin. They even offered assistance: the US Department of Defense announced its readiness to use its satellites to photograph the shuttle in orbit. However, NASA refused. The problem was not considered serious and was not even immediately disclosed to the crew. Furthermore, it remained unclear how light thermal protection could leave a hole in the spacecraft's wing.

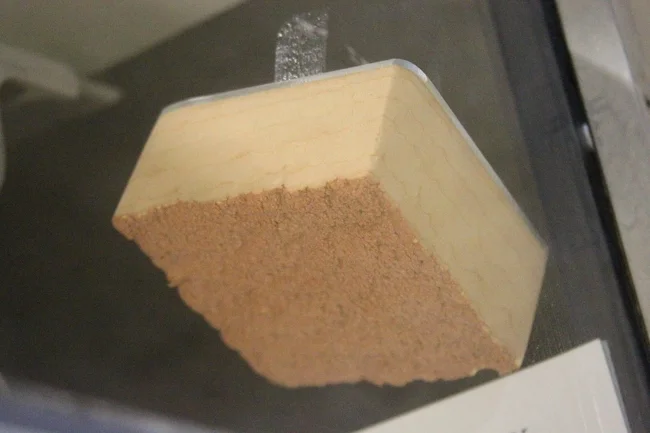

This had to be determined empirically: the investigation committee recreated a similar wing element and fired chunks of frozen foam at it from a cannon. A 0.8 kg fragment of heat shield struck the wing at 850 km/h, leaving a hole approximately 40 cm across. Any doubts were removed: the heat shield was the cause of the Columbia shuttle's demise. As a result, mechanisms inside the wing were left exposed and began to deteriorate from the high temperatures, leading to the loss of the entire shuttle.

A Blockbuster Script

Could the crew have been saved? By the time the astronauts descended to Earth, it was clearly too late to do anything. While the shuttle was in orbit, there was a chance, albeit a slim one. NASA engineer David Baker, who worked on the Space Shuttle program from the very beginning, believes the Columbia crew had the opportunity to return to Earth. However, it would have been one of the riskiest missions in the history of space exploration.

Baker's idea suggested that NASA could have urgently sent the shuttle Atlantis to Columbia's rescue. Its launch was scheduled for March 1, 2003, but theoretically, an expedited launch was feasible. The shuttle Columbia was unable to dock with the ISS due to its orbital position, and the astronauts would have had to transfer to Atlantis via extravehicular activity.

The shuttle Atlantis was supposed to carry two spacesuits (Columbia didn't have any, as the STS-107 mission didn't involve extravehicular activity), and the crew of the damaged shuttle would transfer from one shuttle to the other, two at a time. Atlantis would then descend to Earth, and Columbia would be sent on a self-destruct course. However, shuttles aren't designed to carry such a large number of people, which could have led to problems during landing.

This scenario is well-suited for a heroic film like The Martian, where the astronauts easily disobey orders from their superiors, but in reality, the Columbia rescue mission would have been incredibly difficult and dangerous. Even if NASA had such a plan, the responsibility would have been colossal: in the worst-case scenario, the agency would have lost two shuttles with their crews. And heartless statistics say that the loss of one spacecraft is better than two.

After the Columbia disaster, NASA was left with three shuttles—Endeavor, Atlantis, and Discovery. They flew until the summer of 2011, after which the program was discontinued. The shuttles were left in museums, and NASA is now developing its new Orion spacecraft.

Add your comment

You might be interested in: