Anna Coleman Ladd and Her Masks for Broken Faces (12 photos + 1 video)

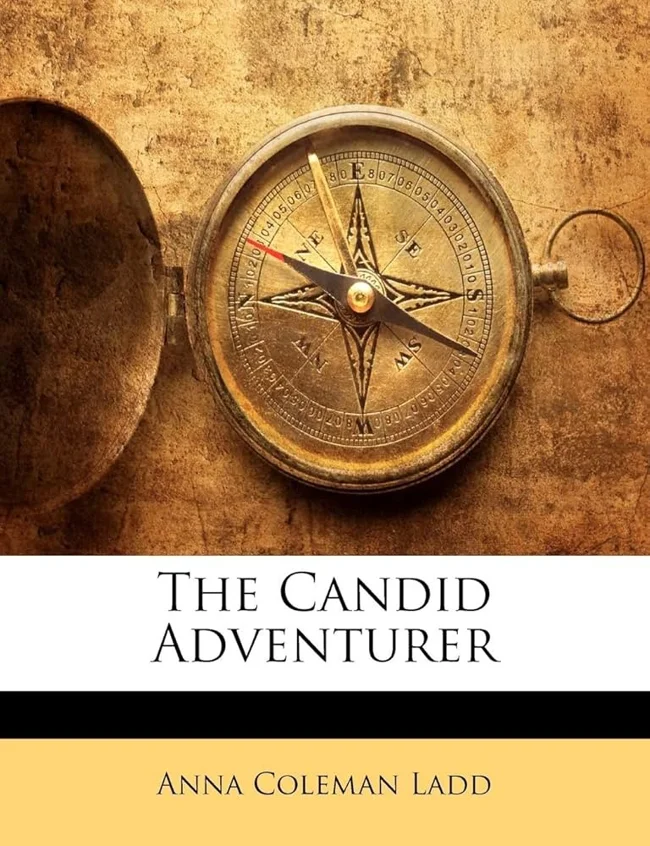

On the eve of World War I, artist and sculptor Anna Coleman Ladd turned her talent to a different, more unusual creative outlet. She wrote a novel.

"The Frank Adventuress," published in 1913, tells the story of portrait artist Jerome Lee, obsessed with superficial beauty and incapable of seeing beyond the superficial. Another heroine, Mary Osborne, is tormented by the feeling of being disconnected from the problems of those less fortunate. Her privileged status shields her "from the touch of life, from humanity in its brutality, evil, and suffering," even as her daughter Muriel tries to pull her mother out of her emotional isolation.

This book became a kind of omen for Ladd herself. Just a few years later, she would voluntarily leave the comfortable life of a recognized artist in Boston and move to Paris, where a line of soldiers with horrific facial injuries awaited her. Using all her sculpting skills, Ladd created individual masks, restoring lost noses, damaged eyes, and shattered jaws.

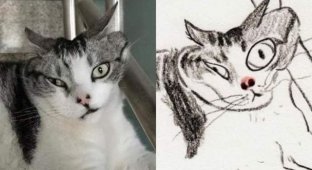

Anna in her youth

She invited them to her studio, created a cozy atmosphere, and allowed them to leave with an exact replica of what the war had taken from them. What would later become the work of plastic surgeons with their scalpels, Ladd accomplished with copper, plaster, and paint. She did this not only for those, like Jerome Lee, who shuddered at the sight of disfigured faces, but also for the soldiers themselves, who feared being forever outcasts in society.

Anna Coleman Watts was born in Pennsylvania in 1878 to a wealthy family, which allowed her to receive an excellent education in literature and art in both America and Europe. In 1900, she studied sculpture in Rome with leading masters. Returning to the States, she completed private commissions for wealthy women.

Her already high social standing was further enhanced by her marriage to Dr. Maynard Ladd in 1905. Moving to Boston, Anna studied at the Museum School and soon became a local celebrity thanks to her paintings and busts.

In 1917, art critic C. Lewis Hind brought an article by Francis Derwent Wood to her attention. An artist in his early forties, Wood joined the Royal Army Medical Corps. After seeing horribly disfigured men being delivered from the front to his colleague, London surgeon Harold Gillies, Wood opened the "Facial Deformity Mask Department" at the Third London General Hospital, soon nicknamed the "Tin Nose Shop." Its goal was to complete the surgeon's work by creating cosmetic prosthetics to fill the gaps left by the war.

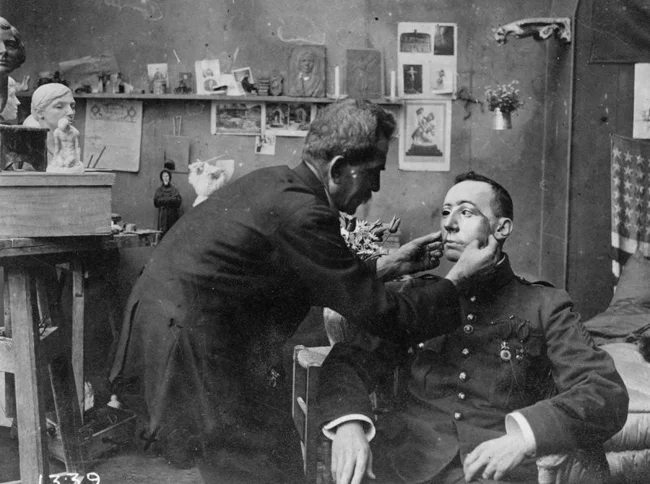

Anna Coleman Ladd tries on a mask

Ladd was convinced that her skills would allow her to achieve similar, if not better, results. Thanks to her doctor husband's connections, she gained an audience with the American Red Cross, which agreed to help open a studio on Paris's Left Bank. She arrived in France in December 1917, and by the spring of 1918, her "Portrait Mask Studio" was ready to accept patients.

Soldiers on the front lines of World War I faced heavy fire and shrapnel. Trench warfare meant that a head poking out of a trench often found itself in the line of direct or ricocheting fire. Helmets protected against fatal wounds, but they could also shatter into shrapnel, piercing the face. Of the six million men who fought in Britain and Ireland, approximately 60,500 suffered head or eye wounds.

Anna Coleman Ladd and her assistant work on a new mask.

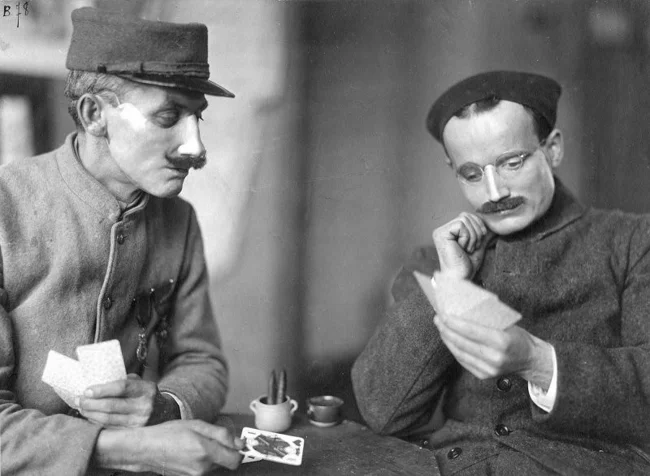

After treatment, these men had great difficulty returning to normal life. They were embarrassed by their appearance and spoke of the "Medusa effect": a passerby, seeing their sunken cheekbone or empty eye socket, might faint. In England, where Gillies worked, blue benches near hospitals were reserved for men with disfigured faces; this color also served as a warning that the occupant's appearance might be shocking. The French called such soldiers "mutilés" (mutilated) or "gueules cassées" (broken faces). Some of them, overcome with despair, voluntarily committed suicide.

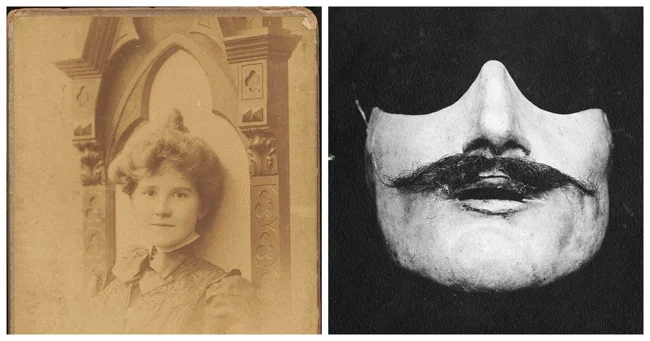

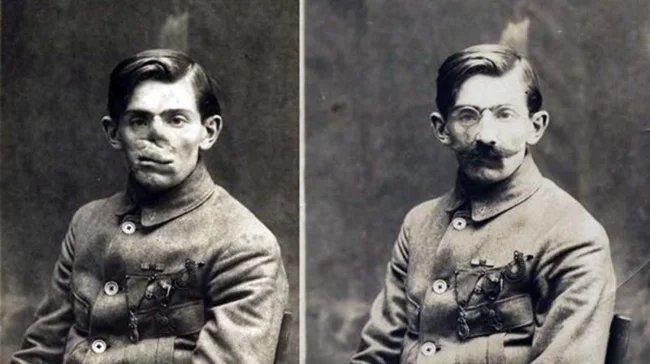

A soldier with a missing chin (left), who was fitted with a special device by Anna Coleman Ladd (right).

It was these men that Anna Ladd sought to help. She established a correspondence with Wood to learn techniques for creating facial prosthetics. Although masks to conceal deformities had been used for centuries, no one had previously attempted to produce them on such a scale. An estimated 3,000 French soldiers needed such assistance. To visit Ladd, they needed a letter of introduction from the Red Cross.

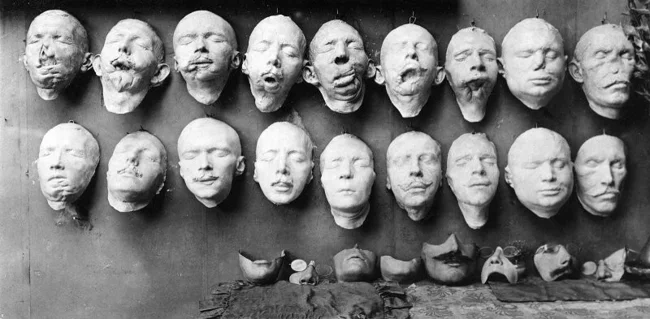

The top row of casts shows the first stage of the process: they were created from molds of the soldiers' disfigured faces. The bottom row of castings shows molds with restoration work performed by sculptor Anna Coleman Ladd.

Her method involved creating a plaster cast of the patient's face. She insisted on a warm and welcoming atmosphere in the studio, where she and her four assistants strove to make the soldiers as comfortable as possible. The staff was trained to joke and not focus on the guests' appearance. Ladd then applied plaster to the face, creating a hard cast. From this cast, a gutta-percha mold for the future mask was made, which was then coated with a thin layer of copper using electroplating. Sometimes, a silver mesh coated with plaster was also used. Lost facial features were recreated from pre-war photographs. The copper layer was no more than 0.75 cm thick, and the finished mask weighed between 115 and 250 grams. It could cover either a missing nose or most of the face, depending on the extent of the damage.

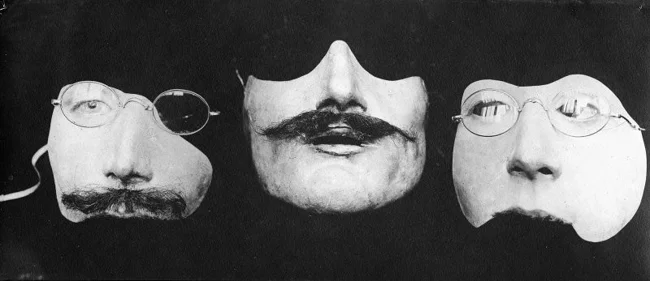

Various portrait masks created by Anna Coleman Ladd

Ladd's artistic skills then came into play. She used water-resistant, oil-based enamel and tried to match the skin tone to a point somewhere between her appearance on a cloudy day and in bright sunlight. If a mustache was needed, she fashioned it from thin foil. Human hair was used for eyebrows and eyelashes. The mask was usually attached to glasses, the temples of which were tucked behind the ears, or with a headband that also encircled the head.

In 1918, Ladd explained to the press:

Our work begins when the surgeon has completed his. We don't undertake healing. We begin when the wounded is discharged from the hospital. The main difficulty is to precisely align the two sides of the face and restore the features so that there is nothing grotesque in the mask. A mask that doesn't resemble the person as their family knew them will be almost as bad as the deformity itself.

It took about a month to make one mask. Ladd spent a total of 11 months in Paris. Some sources claim her studio produced over 200 masks, but the actual figure is likely closer to 100. Considering the labor-intensive process for herself and four assistants, this was a staggering output—about nine masks per month. After the war, she returned to Boston to pursue a career as a sculptor. In 1932, for her contributions, she was awarded the title of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Anna Coleman Ladd died in California in 1939 at the age of 60, just three years after retiring.

In the post-war years, Ladd lectured and spoke openly about her experiences. She received letters from men thanking her for helping them feel more confident. However, no large-scale studies have been conducted on the subsequent fates of these soldiers, and it's difficult to say how seamlessly the masks integrated into their daily lives.

Furthermore, the masks themselves weren't permanent and rarely lasted more than a few years. Even if they did, the patient would undergo a strange metamorphosis: they would age, but the mask would not. Over time, the contrast between the flawless copper plate and wrinkled or faded skin became all too noticeable.

Some of those Ladd helped could live for years in relative peace. Others may have been granted only brief moments of normalcy, when the soft light and company of close friends made them forget what the war had taken from them. But in some way, Anna Coleman Ladd managed to use her artistic talent to give these men a respite from the misery that had been the price of their bravery. In the photographs of the soldiers wearing her masks, many are smiling.