A Forgotten Knot System: Incan Accounting, a Secret Code, and a Lost Language (16 photos)

The great Inca Empire, whose monumental cities, elaborate roads, and complex social structure are still admired today, seemed to have it all.

However, they lacked one key tool—a traditional hard-copy writing system.

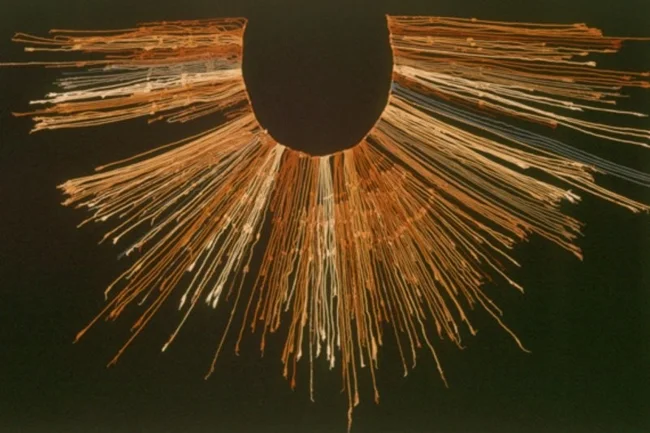

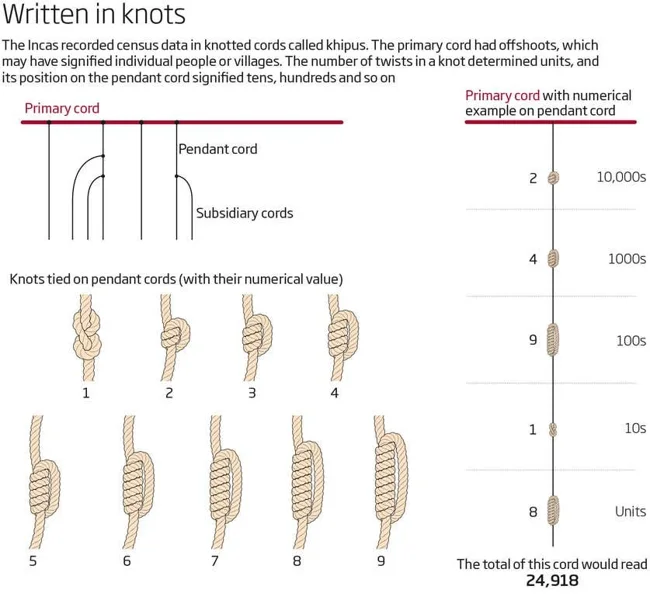

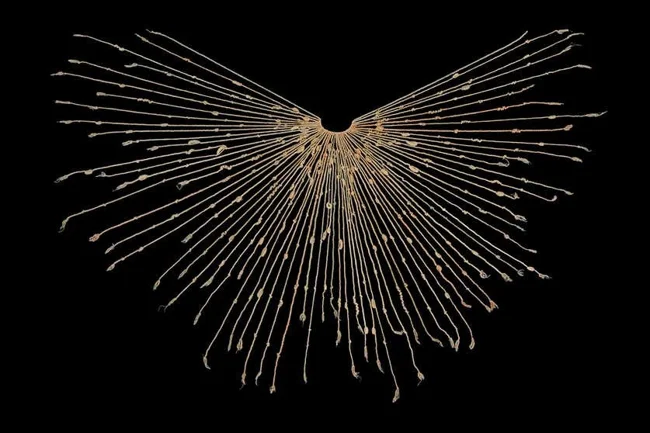

An example of a quipu from the Inca Empire. More complex versions contained up to 1,500 or more lines.

The official language of the empire was Quechua, but there was no alphabet or hieroglyphs for writing it. Therefore, the chronicles of this civilization are known primarily from the accounts of the Spanish conquerors.

The ancient Inca city of Machu Picchu

But the Incas themselves found an ingenious solution to this problem, creating their own complex system of accounting and communication—the quipu, woven from ropes and knots.

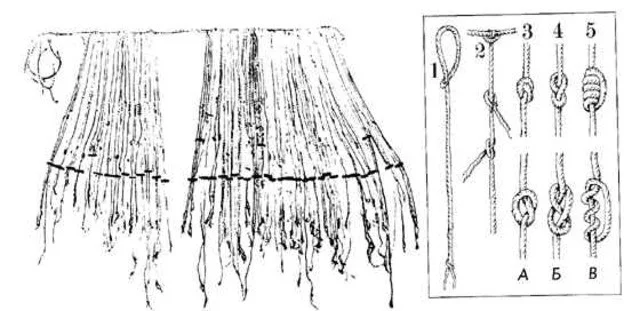

This device consisted of a main cord, from which extended numerous threads of wool or cotton, dyed in different colors. Knots were tied in these threads, and the knot placement, type, number of turns, and the shades of the threads themselves contained an encrypted meaning.

Thus, the numbers one through nine were encoded by the coils within the knot, a figure-eight signified a constant, and an empty section of cord could symbolize zero. By combining these elements, specialists could record a vast array of data.

The use of textiles as a medium was logical for a culture where the quality and complexity of the fabric directly indicated the status and power of its owner.

Working with quipus was the privilege of a select few—special officials known as quipucamayocs. They served in the courts of rulers and chieftains, responsible for collecting taxes, conducting censuses, accounting for resources, and other administrative tasks.

They were essentially living servers, storing the empire's data in a three-dimensional, tactile format.

Today, the secrets of this craft are lost. Modern researchers generally agree that the quipus were used for numerical record-keeping, acting as an ancient ledger using the decimal system. However, there are also bold hypotheses.

Professor Gary Arton of Harvard suggests that the system may have been based on binary code, allowing for the recording of not only numbers but also language elements—phonemes or entire concepts.

In this case, the quipu transforms from a calculator into a fully-fledged writing system, the only one in the world that uses three-dimensional space. This theory is sometimes supported by a hypothetical decoding of the name of the settlement, Puruchuco, which, according to Arton, is encoded in a simple numerical sequence.

It was fear of this hidden ability to communicate that led to the tragic fate of most quipus. The Spanish conquistadors, fearing secret correspondence between conquered peoples, destroyed these artifacts en masse.

Chronicles have preserved revealing stories: how quipu keepers, upon seeing strangers, would retie the knots on the fly, changing the information, or how an old Indian confessed that his bundle contained a record of all the invaders' deeds, both good and bad. For this revelation, both the quipu and its owner were destroyed...

No more than a few hundred such systems survive to this day. They are scattered throughout museums around the world and carefully preserved by some Andean communities as sacred relics.

Even today, in ritual ceremonies, one can see how the descendants of the Incas use the quipu not as a text or a record, but as a silent yet meaningful symbol of connection to a great past, the reading of which, perhaps, still awaits its time.