17th-century leather bonds that still manage to generate income (7 photos)

In the world of finance, there are special obligations that have no maturity date. These are called perpetual bonds. As the name suggests, they last as long as the issuer deems fit. This allows the owner to receive dividends for years.

While such bonds appear attractive for long-term investments, in reality, this is not the case. The only beneficiary of this arrangement is the issuer, who attracts funds that they are theoretically not obligated to repay. The investor, on the other hand, receives annual payments at an interest rate set by the issuer, often intentionally low. Adjusted for inflation, the real value of these payments only decreases over time.

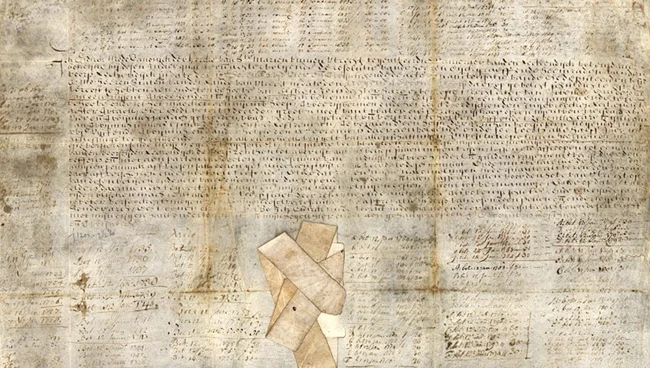

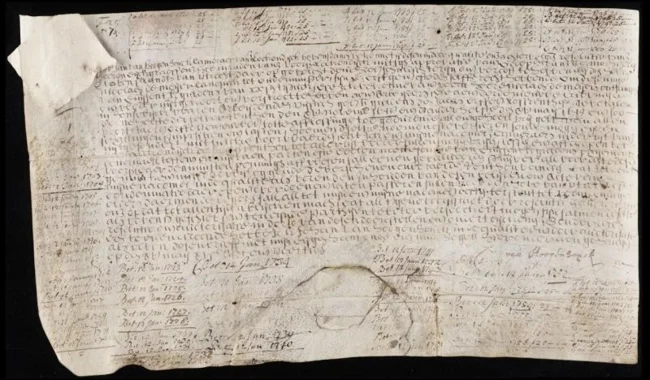

A 1624 Lekdijk Bovendams bond that continues to pay interest after over 400 years

The beauty of a perpetual bond is its negotiability. The company won't redeem it, but the owner can sell the bond on the market, and the right to receive interest will then pass to a new owner. Some such bonds have been passed from hand to hand for centuries, passing through generations of holders.

The most famous example is the British Consols, issued in 1751. They circulated for over two and a half centuries until the government bought them back in 2015.

The immediate reason for the bond issue in 1624 was the dam burst, which left a significant part of Utrecht and Holland underwater.

However, there are bonds issued as early as the 17th century that still regularly pay interest. They were issued by the Dutch water authority Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams, responsible for the dams and canals on the lower Rhine. In 1648, the Authority issued a perpetual loan to finance the construction of a system of locks to regulate the river's flow and prevent erosion.

Each bond was worth 1,000 guilders (approximately $500 today) with an initial interest rate of 5%. Later, in the 17th century, the rate was reduced to 3.5%, and then to 2.5%.

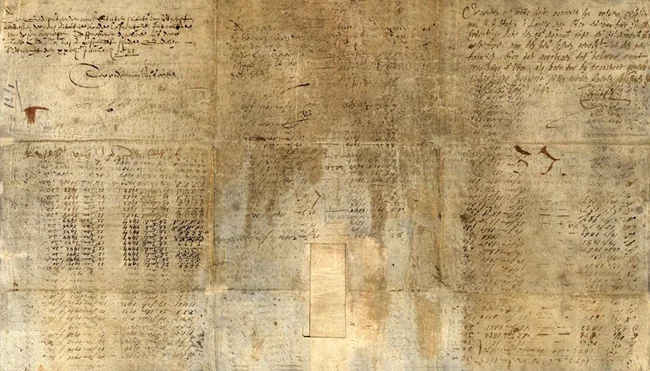

The fight against water fostered cooperation and joint financing. This is evidenced by the numerous stamps affixed to these maintenance instructions—the oldest of which dates back to 1323.

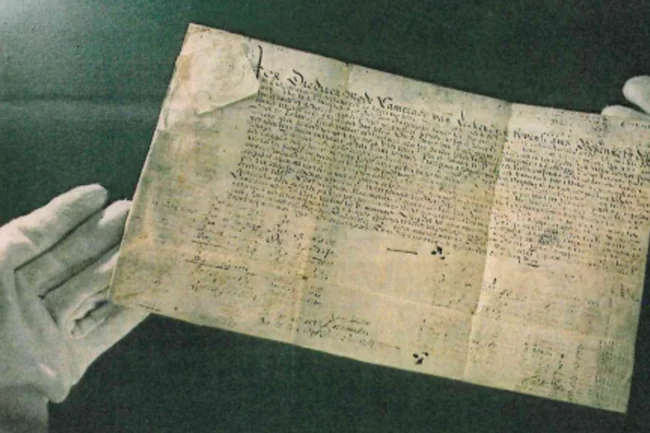

For four centuries, this security traveled the world until it was purchased by Yale University at auction in 2003 for approximately $27,000. The university faced the question: what to do with the acquisition? Unlike most archival documents, which have only historical value, this Dutch bond remained a valid financial instrument. Should it be archived or presented for payment?

Today, interest payments are recorded on a separate document, but they were originally indicated on the original bond certificates of the 17th century.

The bond itself is made not of paper, but of tanned goatskin, and the interest was written directly on the surface. By 1944, the free space on the leather ran out, and a paper appendix was attached to the document for new payment records.

Timothy Young, curator of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, tracked down the legal successor to the original issuer—the Hoogheemraadschap De Stichtse Rijnlanden water authority—and asked if they acknowledged the liability. The answer was affirmative.

A 1648 bond written on goatskin

In 2015, Young traveled to Amsterdam to collect 12 years' worth of accrued interest. The amount was 136 euros. This procedure was necessary to preserve the bond. The administration informed him that this bond was one of only five known to survive.