Glass floats – sea treasures from both ends of the world (13 photos + 1 video)

For over twenty years, an unusual treasure hunt has been taking place on the coast of the American state of Oregon. In the town of Lincoln City, over three thousand fragile and beautiful objects—handcrafted glass balls—are hidden annually on public beaches, waiting for any lucky person to find them.

This game is called "Found It, Take It," but it has a deep and romantic backstory. For decades, long before this holiday, the sea itself gifted people with similar balls, washing them ashore after winter storms.

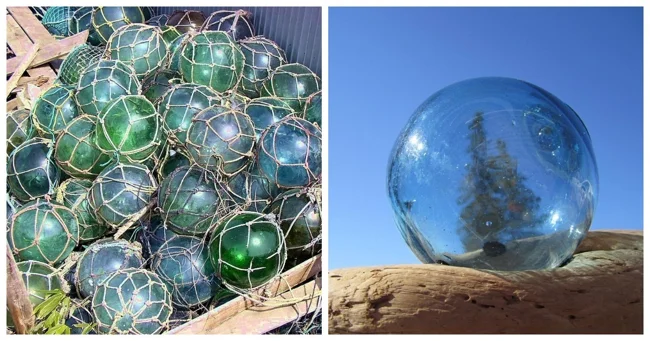

These fragile spheres are more than just decorations. They are glass fishing floats, true working tools of the past. They kept kilometers-long nets afloat in the open ocean. Although they have long been replaced by plastic and aluminum floats, the spirit of the era of these lost glass spheres lives on in collectors and on the waves.

Their story began in Norway. In 1842, the glass company Hadeland Glasverk brought to life the idea of Bergen merchant Christopher Fay. Previously, fishermen used wood and cork, which quickly became damp, were destroyed by woodworms, and eventually failed. Glass proved a revolutionary material—lightweight, durable, and virtually indestructible in saltwater. It quickly became the standard for European fishing, although it wasn't until the mid-20th century that it completely replaced traditional materials.

Around 1910, glass float production began in Japan, and it was this country that left the most significant mark on the industry. The Japanese deep-sea fleet used them extensively for sixty years before switching to modern materials in the 1970s. During this time, countless floats were torn from their nets and lost in the ocean. Most of those still adrift in the Pacific Ocean are of Japanese origin.

Currents carry them in circular patterns, but sometimes they wash ashore—on the west coast of the US and Canada, in Taiwan, and on the beaches of Micronesia and Polynesia. They are even found on remote islands in the Caribbean and in Europe.

A genuine float is easy to identify. Most have a greenish tint, as they were often made from recycled sake bottles. Pale purple specimens are rarer. Perhaps the once-transparent glass, containing manganese, changed color over time under prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light. But the brightly colored floats—scarlet, neon green, cobalt blue—are modern replicas for souvenir shops.

The real story is written in the glass itself. Air bubbles and natural inclusions are visible inside, and the outer surface bears the marks of years of ocean battering—scuffs and chips. A stamp or logo with Japanese characters can often be found on the ball. The sea washed ashore balls of various sizes—from 5 to 50 centimeters in diameter—for different types of fishing and nets. The largest specimens are truly rare today and a great success for collectors.