Could a world exist where cats, tails up, flee in terror from mice, taking refuge in trees?

Yes, and not in a science fiction movie, but in the harsh reality of tranquil Australia, where floods of mice regularly occur, turning life into a nightmare.

In 1917, the country experienced one of its most widespread infestations, when trillions of rodents devoured everything in their path—from crops to telephone wires.

Australia is waging a perpetual war against invaders, but the most terrifying of these aren't giant spiders or venomous snakes. They're the gray hordes of common mice, whose raids transform fertile regions into ecological disaster zones. Every few years, their population reaches biblical proportions, descending on fields, shops, and even Australian bedrooms. Scientists estimate that Sydney alone is home to between 500 million and a billion rodents, or up to a hundred for every resident.

But even against this backdrop, the Great Mouse Plague of 1917 stands out. Then, the states of Queensland and Victoria were literally buried under a living, writhing mass. The mice devoured standing wheat, chewed through leather shoes, tablecloths, and books. They bit babies in cradles, tore down telegraph wires, and hid in parcels at the post office.

Women flinched and squealed as they opened cupboards, only to see dozens of rodents scurry out. Dead mice floated in milk jugs, and their carcasses baked in loaves of bread.

"Cats Flee in Panic from Mice"—the sensational newspaper headlines of 1917—sounded absurd. "The unfortunate animals are so terrified that they climb trees and chew grass, while mice run along their backs and gnaw at their ears!" wrote The Richmond River Herald.

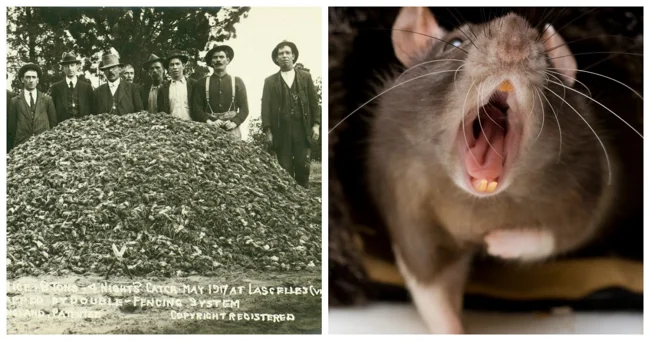

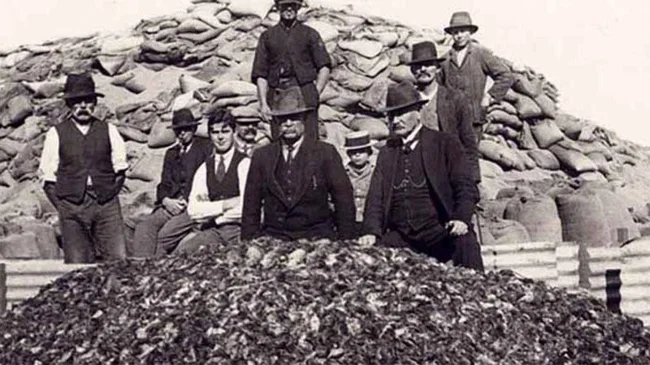

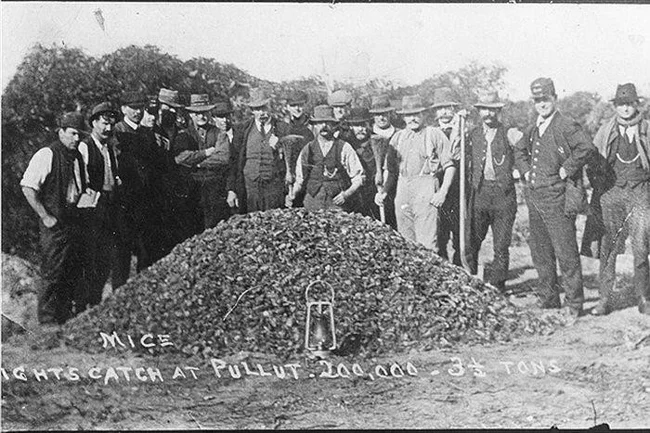

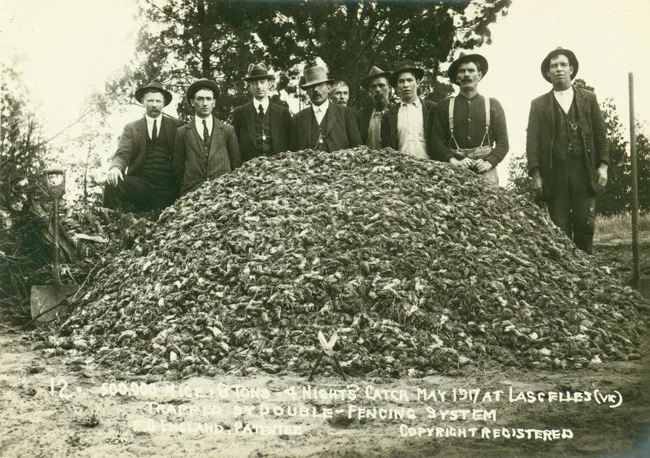

Farmers lost their harvests in a matter of days. "We are forced to burn the hay—it's swarming with rodents," reported The Horsham Times. In the town of Lascelles, Victoria, 500,000 mice—three tons of live weight—were caught in a single night! Two women in Rochester went down in history as the "Mouse Butchers," killing over a thousand rodents with their bare hands in two hours.

The peak of the infestation occurred between April and August 1917. By its end, the Australians had exterminated 1,500 tons of rodents (approximately 100 million individuals).

Why is this happening again?

Mice are not native to the continent. They arrived on European ships in the 18th century and, lacking natural enemies, multiplied to alarming levels. Scientists attribute outbreaks to heavy winter rains, although laboratory experiments do not always confirm a direct link to food and water availability.

Today, ecologists have learned to predict infestations using mathematical models, giving farmers a chance to prepare. But the 1993 mouse apocalypse, which caused $96 million in damage, reminds us that the war on rodents is not over.

Several years of desiccating drought gave way in 2020 to long-awaited rainfall, giving farmers record harvests. However, this gift of fate also had a dark side. Colossal harvests, coupled with warm, humid weather, created a veritable paradise for mice. And the lack of sufficient natural guardians in the region—owls and snakes—allowed the gray swarms to multiply to apocalyptic proportions.

It took place in New South Wales, Australia, in 2020, 2021, and 2022. Residents of the region lived in constant stress, farmers lost their crops, and the inexorable gray swarms once again demonstrated how powerful and potent a force of nature can be, even if it's formed by little gray mice.

Add your comment

You might be interested in: