The Tomb of Cyrus, Surviving Millennia of Earthquakes (10 photos + 1 video)

Natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes, and earthquakes were always considered manifestations of the will of the gods in ancient times. But for centuries, our ancestors refused to blindly submit to the wrath of higher powers.

They built dams to protect their homes from the elements, and the houses themselves became a challenge to nature. Historical and archaeological research shows that ancient civilizations possessed a profound understanding of earthquake-resistant construction.

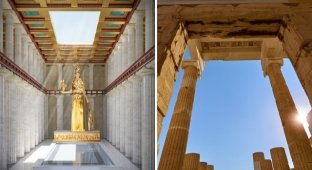

For example, in ancient Crete, many buildings were constructed from stone blocks joined by wooden elements. This gave the rigid structure flexibility, preventing cracking during earthquakes. Other structures were erected on a layer of sand or loose gravel, which absorbed vibrations. The Temple of Athena at Troy (1500 BC) and the Doric temples at Paestum (273 BC) rest on thick sand cushions.

Another technique originated in ancient Greece and Persia. A layer of special material, such as ceramic or clay, was placed between the soil and the foundation. During an earthquake, one layer would slide over the other, minimizing damage from tremors. This principle, known as seismic base isolation, remains one of the most effective methods of protecting buildings today. Modern engineers use rubber mounts, ball bearings, and spring systems for this purpose.

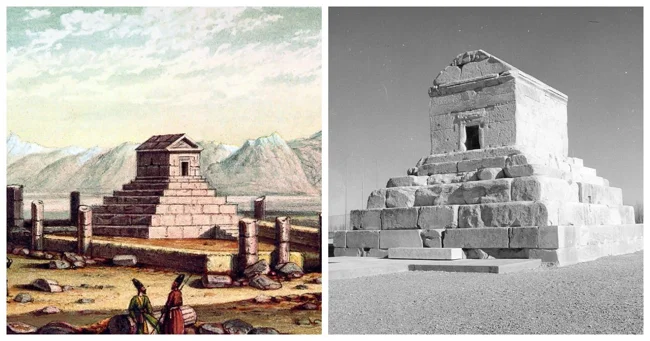

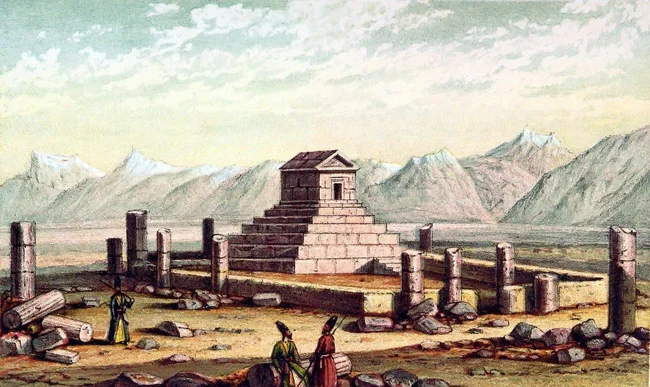

One of the oldest examples of this technology is considered to be the tomb of Cyrus the Great in Pasargadae, the capital of the Achaemenid Empire in modern-day Iran. Despite the fact that Cyrus ruled a vast empire stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indus River, his mausoleum is surprisingly modest. The cubic tomb is constructed of large stone blocks and sits on a six-tiered pyramidal base.

The structure's foundation consists of several layers of limestone. The bottom layer, or base, is composed of stones bonded with lime mortar, ash, and sand, and carefully leveled. The upper layers are constructed of blocks connected with metal clamps, but not anchored to the base itself. This design allowed the upper part to slide along the foundation during tremors.

Clearly, the Tomb of Cyrus has withstood more than one earthquake during its 2,500 years. However, it is unknown how strong these tremors were, and whether they actually activated the isolation mechanism. There are no visible signs of displacement on the blocks, which raises the question: did the system work as intended, and did the ancient architects understand what they were doing? And the most ironic detail is that it is not known for certain whether Cyrus the Great himself was actually buried in this tomb.

According to the Greek historian Arrian, a former commander of Alexander the Great, the king visited the tomb after the sack of Persepolis. Inside, soldiers discovered a golden bed, a table with vessels, a golden coffin, jewelry with precious stones, and an inscription: "O traveler, I am Cyrus, who gave the Persians an empire and was king of Asia. Do not deny me this monument."

There is no archaeological evidence for this epitaph. Even among ancient historians who mention it, there is disagreement about the exact text. The tomb was plundered shortly after Alexander's visit, and upon his return, the king ordered its restoration. If the inscription had been destroyed, it would certainly have been restored. The complete lack of epigraphic evidence casts doubt on the veracity of this story.

Therefore, the tomb may not belong to Cyrus. And the effectiveness of the sophisticated anti-seismic technology is questionable. The only detailed study of this system was conducted by the Islamic Azad University in Iran. The authors claim to have simulated the tomb in software and subjected it to a virtual strong earthquake, reaching a positive conclusion. Unfortunately, their scientific paper is not publicly available, and questions remain unanswered.