Impossible Colors: Why We See the World Differently (4 photos)

Color is electromagnetic radiation in the optical range. But how we see it depends on how our eyes and brain work.

The human retina contains three types of color receptors—cones. Each type responds to a specific range of light waves: red, green, or blue. These wavelengths overlap, so we see not only the primary colors but also their combinations—for example, white (a mixture of all spectral colors) or orange (red and yellow).

But there's a catch: the brain processes color information through a system of color opponents—oppositions:

Red versus green;

Blue versus yellow;

Light versus dark.

This theory was proposed back in 1872 by the German physiologist Ewald Hering (August 5, 1834 – January 26, 1918). The idea is simple: the perception of one color precludes the perception of its opposite at the same point in the visual field. This can be compared to the inability to simultaneously bend and straighten your arm.

Impossible Colors

Because of the opponent system, so-called "impossible" or "forbidden" colors exist—reddish-green and yellowish-blue. Our brains simply can't adequately process them simultaneously, but scientists have found a way to trick this system.

In 1983, Hewitt Crane and Thomas Piantanida, researchers at Stanford University, conducted an experiment. Using special equipment, they stabilized the image on participants' retinas so that each eye saw only one color (for example, the left eye saw red, the right eye saw green). Six out of seven subjects reported seeing "impossible" colors—new shades that simultaneously appeared both red and green.

However, the experiment participants were unable to fully describe these colors because humanity lacks words for them.

The Dress Phenomenon

On February 26, 2015, a photograph of an ordinary dress went viral. Tumblr user Caitlin McNeil posted the image and asked, "What color is this dress—white and gold or blue and black?"

68% of BuzzFeed users saw the dress as white and gold. The rest were sure it was blue and black. The manufacturer, Roman Originals, had to intervene in the debate and confirmed that the dress was indeed blue and black. The white and gold version was never in their collection.

Why did people see the dress differently?

There is no definitive explanation, but there are two complementary hypotheses:

Neuroscientist Bevil Conway's Hypothesis

Our brains interpret lighting differently. The photograph of the dress was taken with bright backlighting, the source of which was unknown. This created ambiguity.

Some people assumed the dress was illuminated by natural daylight, so they subconsciously subtracted the blue tones from the image (daylight contains a lot of blue) and saw a white and gold dress.

People who assumed the lighting was artificial (warm, with a yellow tint) subconsciously subtracted the yellow tones and saw a blue and black dress.

Neuroscientist Pascal Wallisch's Hypothesis

A study of 13,000 people showed:

"Larks" (people accustomed to bright daylight) were more likely to see the dress as white and gold.

"Night owls" (those who spend more time under artificial light) said the dress was blue and black.

Age also plays a role: with age, the retina begins to perceive blue less effectively, which affects the perception of shades.

How to see "impossible" colors yourself

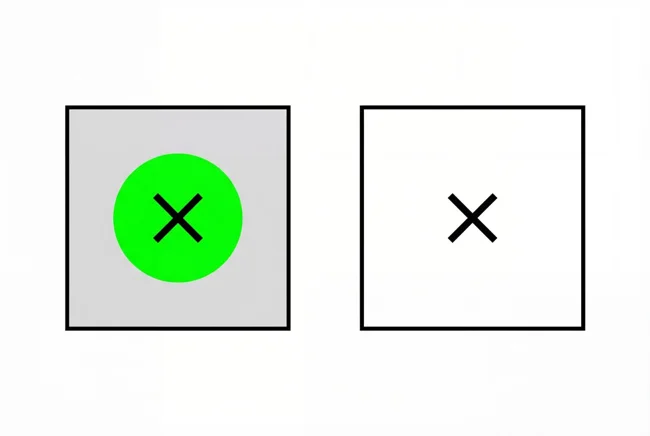

I suggest you try a simple afterimage experiment. Stare at the cross in the center of the green circle for 30 seconds, then move your gaze to the cross in the white square:

You'll see an afterimage of the opposite color (pink instead of green).

This occurs due to fatigue of the color receptors. But these aren't true "impossible" colors—they're simply an illusion created by your brain.

To see real reddish-green or yellowish-blue hues, complex laboratory conditions are required. However, scientists still debate whether these colors actually exist or are simply intermediate hues.

What does this tell us about our perception?

The dress phenomenon and "impossible" colors demonstrate that there is no single, objective reality of color. What we see depends on:

The characteristics of our eyes and brain function;

The nature of lighting;

Time of day and lifestyle;

Age.

Color is not only a matter of the physics of light, but also an individual interpretation by the brain. We all look at the same world, but we see it differently.