Ariel: Uranus's moon with a 170-kilometer-deep ocean (4 photos)

Among the 29 known moons of Uranus, the 1,200-kilometer-wide Ariel holds a special place—the fourth largest and likely the most geologically active in the past. Discovered by British astronomer William Lassell on October 24, 1851, this moon continues to harbor many mysteries that will remain unsolved for some time to come.

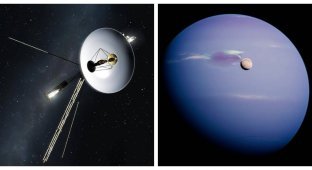

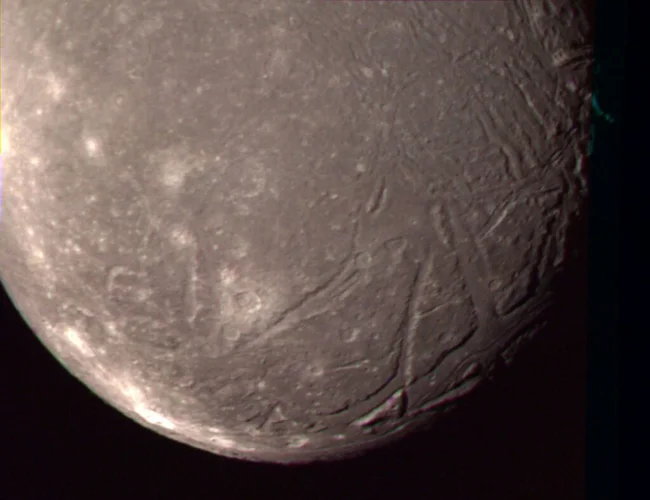

The best color image of Ariel to date was taken by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft on January 24, 1986.

The image was taken from a distance of 170,000 kilometers, and the resolution was approximately three kilometers per pixel.

Ariel's southern hemisphere is a mosaic of three terrain types: ancient cratered plains, fault-cut terrain, and mysterious smooth regions. These features are clearly visible in the enhanced image.

Reconstructed image of Ariel

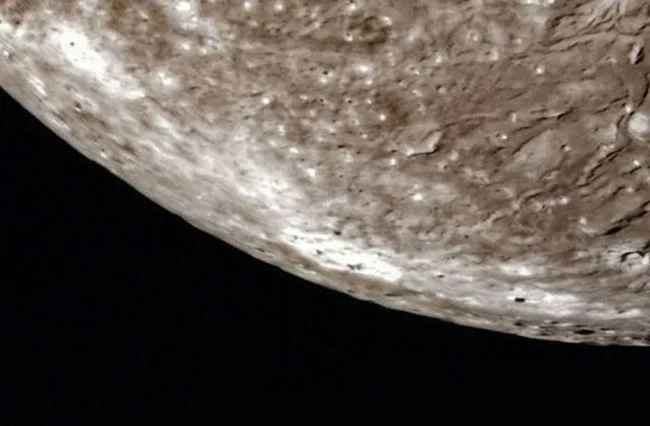

Most of the visible surface is composed of ancient crust, strewn with countless impact features, scarps, and grabens—elongated areas depressed relative to the surrounding terrain.

Of particular interest are the large valleys near the terminator (the boundaries between light and shadow), covered by younger sediments with fewer craters. This is indirect evidence that the moon remained geologically active for a very long time after its formation.

Tidal forces likely provided the geological activity of such a small celestial body: the constant stretching and compression of Ariel during its gravitational interaction with Uranus and other massive moons maintained the interior's heat for a long time.

An ocean again?

In October 2025, scientists from the Planetary Science Institute (USA) published a study suggesting that a global ocean more than 170 kilometers deep may be hidden beneath Ariel's icy crust. For comparison, the average depth of the Pacific Ocean is only four kilometers.

Even earlier, in July 2024, NASA's James Webb Space Telescope discovered on Ariel's surface some of the richest deposits of carbon dioxide in the Solar System, as well as carbon monoxide. Far from the Sun, without an atmosphere or magnetosphere, these compounds should quickly be destroyed by cosmic rays. But they are there! Therefore, a mechanism exists that ensures the constant replenishment of these deposits. Most likely, a subsurface ocean, venting through cryovolcanoes, is responsible.

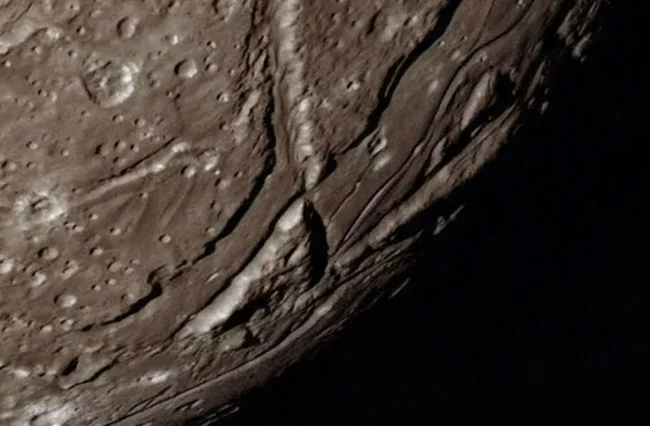

In February 2025, researchers from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (USA) suggested that deep grooves on Ariel's surface may be "windows" into the moon's interior, similar to the faults at the south pole of Saturn's Enceladus.

The Uranus system is so fascinating that the scientific community is pushing for a dedicated mission to study both the planet itself and its large moons, including Ariel. A concept for such a mission, called the Uranus Orbiter and Probe, already exists. Its launch is scheduled for the second half of the 2030s, with arrival in the ice giant system in 2044.