How Dr. Campbell used bats to fight malaria (8 photos)

Decades ago, the United States took on a monumental challenge: eradicating malaria from its entire territory.

It was from this plan that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the nation's premier public health institute, was born. For four years, the CDC sprayed malaria dust in millions of homes across the country. The results were stunning: in just three years, malaria cases dropped from 15,000 in 1947 to 2,000 in 1950. By the end of the following year, malaria was officially eliminated from the United States.

However, the insecticidal properties of DDT were only discovered in 1939 by the Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller. Before then, malaria control was limited to eliminating mosquito breeding sites by draining bodies of water or treating them with poison.

At the dawn of the last century, before malaria became a serious threat, a Texas doctor began an unusual experiment to combat malaria-carrying mosquitoes using bats.

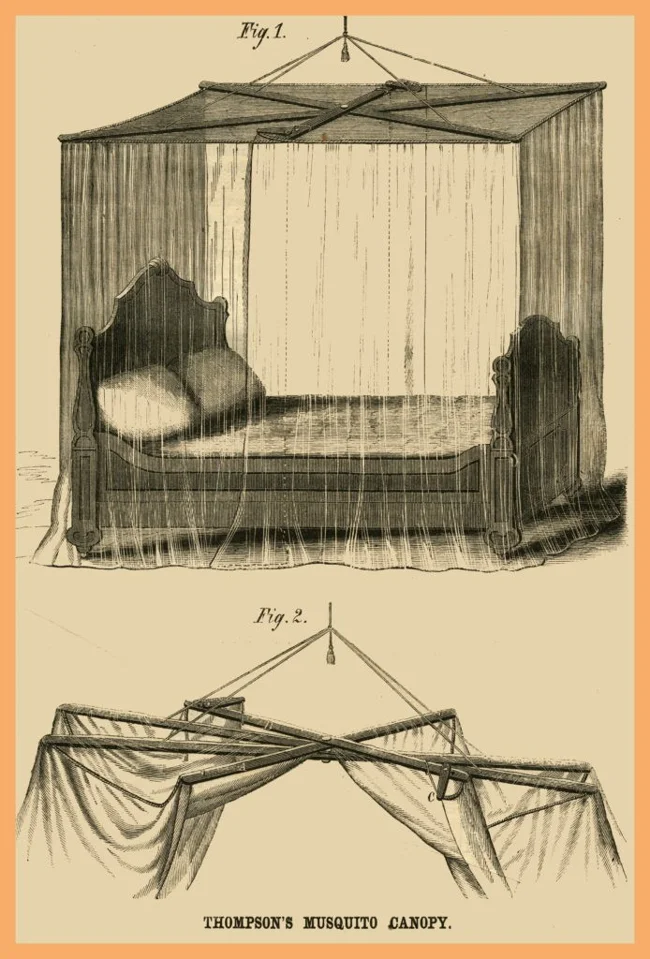

One of the first mosquito control devices was the Thompson mosquito canopy, patented in the 1850s.

At first, Dr. Campbell tried creating nesting boxes for mice out of various shapes and sizes. After several years of failure, he realized that, unlike birds, bats needed something more substantial. Investing $500 of his own money, he built the first nine-meter-tall tower in 1907 on an experimental farm near San Antonio. Inside, he placed slanted shelves for roosting and hung gauze soaked in mouse excrement to create a familiar scent. To further attract nocturnal visitors, he even left slices of ham inside.

Despite all his efforts, not a single mouse took the bait. For three years, Campbell invested his savings in improving the tower, but to no avail. In desperation, he captured about 500 bats elsewhere and locked them in the tower, hoping their squeaking would attract their fellow bats. This plan also failed. In a rage, Campbell destroyed the tower, driving out the hundreds of sparrows that had taken to it instead of the mice.

Bat habitat in the Mexican neighborhood of San Antonio, Texas, circa 1910-1915

Disheartened by his string of failures, the doctor left his medical practice and retreated to the mountains to study bat behavior and habitat alone. Armed with his new knowledge, he returned to work.

A key discovery was that bats prefer to nest near water. Therefore, he built his next tower near Lake Mitchell, a swampy lowland where city sewage flowed, creating ideal conditions for mosquito breeding. Local farmers were forced to abandon their land during the growing season. In the spring of 1911, when the new tower was completed, 78 of the 87 residents of the lake's surrounding area were suffering from malaria.

Mexican bats live in huge colonies, capable of devouring countless mosquitoes in a single night.

And finally, Campbell achieved success. That summer, he observed hundreds of bats flying out of the tower in a continuous stream within five minutes. Knowing the tower could accommodate hundreds of thousands of bats, he decided to relocate the colony from a nearby hunting lodge there. To accomplish this, he made the old lodge acoustically unbearable.

After waiting for the mice to fly off for the night hunt, Campbell and his assistant created an unimaginable cacophony in the house just before their return at dawn. They played a recording of clarinets, piccolos, trombones, drums, and cymbals at full volume. The bats' sensitive hearing couldn't stand the noise, and the colony abandoned the inhospitable location. The same operation was carried out at a nearby abandoned ranch.

The next evening, Campbell timed the flight from his tower. The procession lasted almost two hours. The doctor was convinced that he had successfully relocated all the mice. In 1914, four years after building the tower at Lake Mitchell, he found no cases of malaria among the local residents.

Word of his experiments spread, and requests for towers began pouring in from across the country and even from Italy. The San Antonio City Council, recognizing the impressive results at a modest cost, passed an ordinance banning the killing of bats within city limits. Soon after, the first municipal bat tower was erected there, and killing bats eventually became illegal throughout Texas.

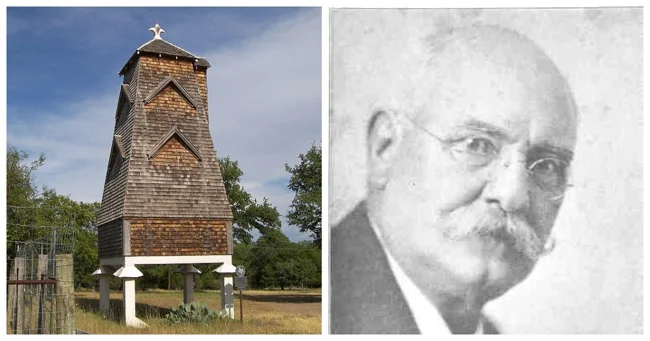

The bat shelter near Comfort, built in 1918, is designated a historic landmark.

The tower near Lake Mitchell has become a tourist attraction. Benches were installed for visitors to comfortably observe the evening flight of the colony, which in its heyday numbered over a quarter of a million individuals.

From 1914 to 1929, 16 such towers were built from Texas to Italy. Only two or three remain, located on private property. The tower near Lake Mitchell was demolished in the 1950s, when the rabies crisis in Texas began, and bats were removed from the list of protected species.

The tower on Sugarloaf Key, Florida, was destroyed by a hurricane in 2017.

One of the surviving towers, built in 1918, stands near the town of Comfort, Texas, on the former mayor's country estate. This pyramidal tower, with its wooden siding, is raised on a concrete foundation, allowing waste to be collected from below. This valuable product, an excellent fertilizer, became a beneficial side effect of the project. For example, the tower near Lake Mitchell produced an average of two tons of manure per year.

The tower in Comfort is called the "Hygieostatic Bat Refuge." The word "hygieostatic" was coined by Mayor Albert Steves, combining the Greek words "hygieia" (health) and "stasis" (condition, basis). Today, the tower is home to about a thousand bats, though their population once reached ten thousand.