Today, there are approximately 80,000 members of the yakuza criminal organizations, known as the Boryokudan, operating in Japan (13 photos)

These structures are divided into large clans, which often engage in violent conflicts over spheres of influence and territory.

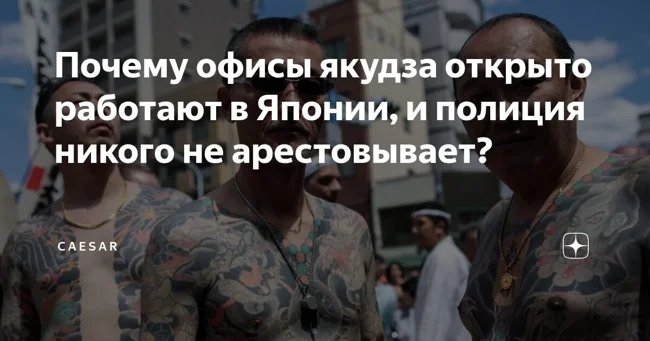

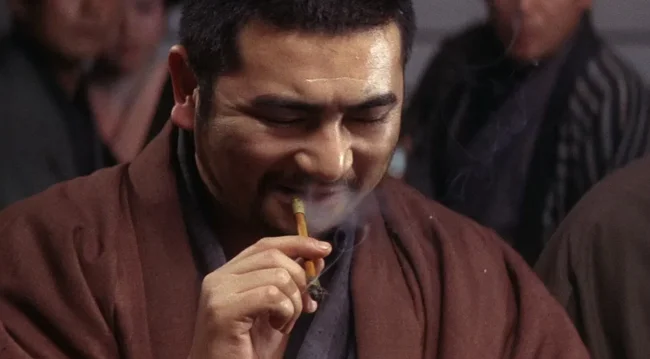

Yakuza members traditionally adhere to a semi-samurai way of life: they cover their bodies with intricate tattoos, adhere to an internal code of conduct, and respect their own unspoken rules.

The Yamaguchi-gumi clan is considered the largest organization—one of the most notorious and brutal criminal groups on the planet. According to various media estimates, its annual income exceeds six billion dollars. These funds come from both illegal activities such as smuggling, loan sharking, racketeering, drug trafficking, and other criminal activities, as well as from completely legal companies owned by the group.

The Yamaguchi-gumi's central office, like the headquarters of other major yakuza clans, operates openly and publicly, for example, in Kobe, Honshu.

This raises a logical question: if the authorities consider the yakuza criminals, why don't the police detain their leaders and shut down their offices?

We'll now try to answer this question in more detail:

Where did the yakuza come from? Let's briefly review key periods in history.

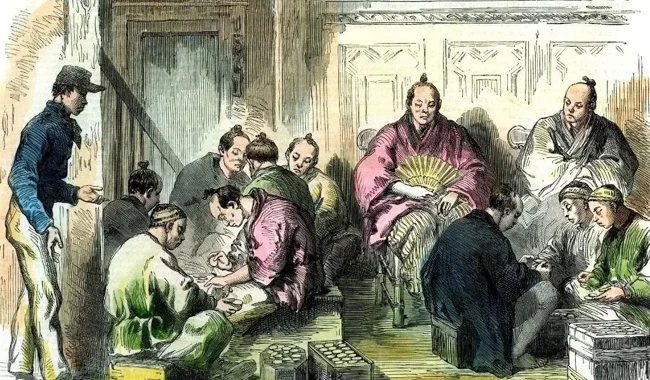

During the Edo period (1603–1868), when Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa samurai dynasty, crime in the country grew as rapidly as the economy. This was due to the rapid development of cities, the increase in the number of merchants, the growth of money circulation, and the emergence of a huge class of people who did not fit into the rigid class system: vagrants, unemployed samurai, ronin (samurai without a master or who had lost their honor), gamblers, and marginal elements.

All this created an ideal environment for the emergence of semi-criminal organizations and street gangs.

As early as the 1640s, the son of a ronin named Banzuyin Chōbei gathered around himself petty lawbreakers—primarily bakuto card players—and formed the first yakuza clan. Over time, burakumin—descendants of the lower caste of "unclean" people who were despised by society, had no place in the official social structure, and sought protection, support, and an opportunity to earn money—began to actively join this group. Thus, a small gang of gamblers gradually evolved into an organized community with the first outlines of a future mafia structure.

Despite his criminal source of income, Banzuyin Chobei adhered to the principles of samurai nobility taught to him by his father. He sought to help ordinary citizens, protecting women from rapists and thieves on the streets where he lived, and also caring for the poor and orphans.

Therefore, the authorities' attitude toward the first group of yakuza was rather lenient. Over time, Banzuyin Chobei was even tasked with recruiting workers for road construction, which strengthened his authority.

Thus, the early yakuza clans began to be perceived by society not so much as criminals, but rather as "public figures" maintaining order where the state sometimes failed.

As early as 1735–1740, municipal authorities in some cities officially appointed yakuza elders as street overseers—a position comparable in status to minor samurai posts.

Police officials often used clan members as informants, providing protection and helping them eliminate rivals. The yakuza protected "their" neighborhoods and actively cleared the streets of thieves, robbers, and hooligans, which enhanced their reputation as protectors of civilians.

It's no surprise that over time, a popular saying emerged: "During the day, the police protect us, and at night, the yakuza."

However, as the number of clans grew, the yakuza's nobility faded, and many groups often immersed themselves in criminal activities, which the government and police had to (really) combat to maintain order on the streets.

Why, then, despite their criminal status, do the yakuza operate openly today?

To understand this, it's important to consider that the yakuza's role in Japanese society has long been paradoxical. On the one hand, they were criminal gangs. On the other, they had a clear hierarchy, strict rules, and occupied a place in the shadow economy often occupied by far more chaotic and violent gangs in other countries.

Therefore, the authorities viewed them not only as enemies, but also as a manageable evil, one that could be controlled and kept in sight, rather than attempting to completely destroy them and lead to uncontrolled chaos.

From the 1950s to the 1990s, yakuza clans actively engaged in criminal activity, eliminating police officers, politicians, and rivals, and waging bloody street wars for turf. Clashes occurred right on the streets of major cities, fueling fear and distrust of the authorities among the population.

When the yakuza's membership approached 100,000, many officials and police officers were corrupted, and large businesses were completely controlled by the mafia, it became clear that a "war of extermination" would only lead to an escalation of violence. The more pressure was placed on the clans, the more fiercely they resisted.

Therefore, by the late 1990s, the government changed its strategy. Instead of directly eliminating the yakuza, authorities began to regulate them, imposing strict legal restrictions while simultaneously allowing them a "legal window" for existence.

As a result, the state gradually tightened regulations: organizations and members of yakuza clans who refused to cooperate with the authorities were prohibited from using banking services, entering into legal transactions, renting cars, and even registering mobile phone numbers in their own names (but this is a more modern law).

Disobedient clans were subjected to administrative pressure, effectively cutting off their access. Meanwhile, yakuza members were unable to buy anything (neither a car nor a home), register a company in their own name, or enter into a financial transaction, even if it was obtained through criminal means.

All these prohibitions and de facto state strangulation forced most yakuza groups to cooperate with the police to avoid complete economic paralysis.

For decades, the authorities' goal was not to destroy the yakuza as a phenomenon, but to transform them from violent street gangs into a structure that was easier to control and monitor. Thus, by 2010, approximately two dozen large clans with a stable and clear hierarchy remained under state supervision. And the total number of yakuza clan members had fallen by 80% compared to the 1990s.

Security expert Hiroki Allen explains it this way: if the yakuza are outlawed and attempted to be eliminated by force, the groups will simply go underground. Then, indiscriminate killings and turf wars will return to the streets, as they did in the second half of the 20th century.

The "controlled transparency" strategy, surprisingly, worked.

Many clans voluntarily abandoned overt violence and switched to white-collar crime: bribery, corporate schemes, extortion, and online fraud. This is still illegal, but far less chaotic and dangerous for citizens than street shootouts.

Today, the headquarters addresses of the largest gangs are officially listed on the National Police Agency website. They have their own offices, emblems, business cards—everything is completely open.

Formally, clan membership itself is not a crime; there is no article in Japanese law that prohibits someone from simply being a member of the yakuza, although any legal activity of the yakuza is classified as organized crime.

However, to arrest a gang member, they must be proven to have committed a specific crime, and the Japanese justice system is very strict in this regard: charges must be perfect, leading police to avoid arrests unless they are 100% confident of a successful conviction.

At the same time, the yakuza continue to maintain their image as "social helpers" by participating in charitable activities: they delivered aid after the 1995 and 2011 Kobe earthquakes and offered their buildings to victims.

By the beginning of the 21st century, many clans had transformed from violent street gangs into controlled, relatively "soft" structures with a minimal rate of fatal crime, although methods of pressure and extortion remain part of their DNA.

Well, that's another story...