Linnaeus's flower clock: how plants help to tell time (7 photos)

As early as the 4th century BC, Androsthenes, an admiral of Alexander the Great, noted that tamarind leaves droop at night, protecting the fruit. Francis Bacon wrote in 1626 that marigolds, mallows and other plants "rejoice in the sun and are sad in its absence." And Shelley sang in verse the praises of mimosa, whose leaves open to the light and fold back with the coming of night.

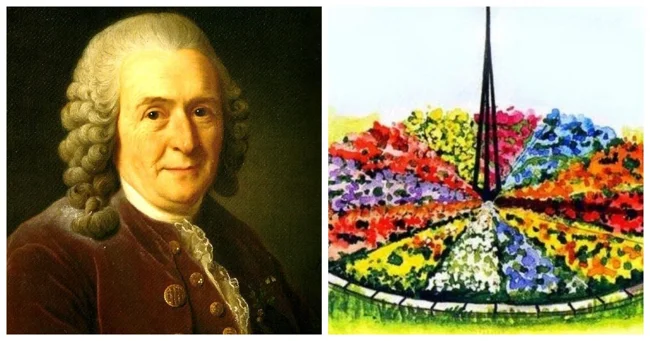

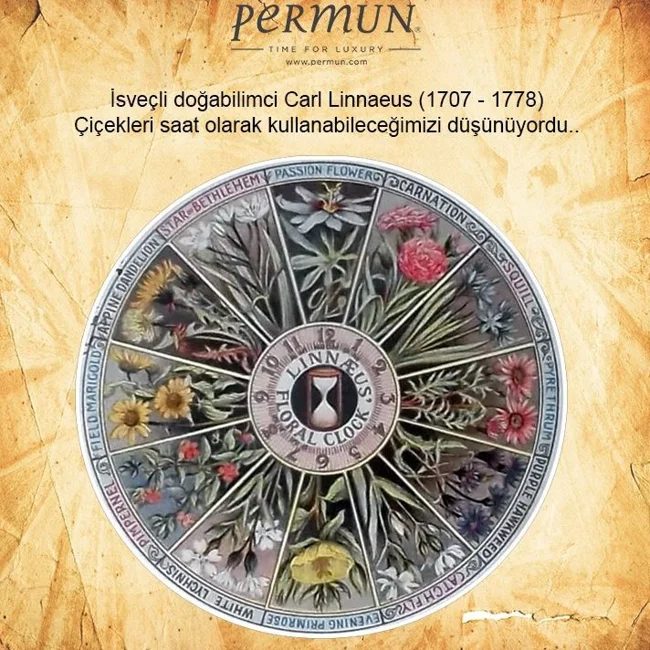

But the one who was most interested in this topic was Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish naturalist and physician, the creator of a unified system for classifying flora and fauna.

Carl Linnaeus

He spent years observing plants that open and close their petals at specific times, and in 1751 he divided them into three groups:

Meteorici — react to the weather.

Tropici — depend on the length of daylight.

Aequinoctales — follow a strict schedule.

By the way, you shouldn't confuse Linnaeus's clock with flower beds in the shape of a dial — the first of these appeared in Paris in 1892.

The Secret Mechanism of Nature

Linnaeus's Flower Clock

Why Aequinoctales plants behave like living clocks has been a mystery to scientists for two centuries. In 1729, the French astronomer de Mairan placed a mimosa in a dark basement. And it continued to raise its leaves during the day and lower them at night. Other experiments confirmed that it was not a matter of light, temperature or humidity. Even artificially alternating day and night only briefly disrupted their rhythm.

Charles Darwin suggested that plants generate their own biological clocks. And in the 20th century, German biologist Erwin Büning linked these rhythms to seasonal changes.

How to make a clock out of flowers?

A flowerbed in the shape of a clock in Edinburgh

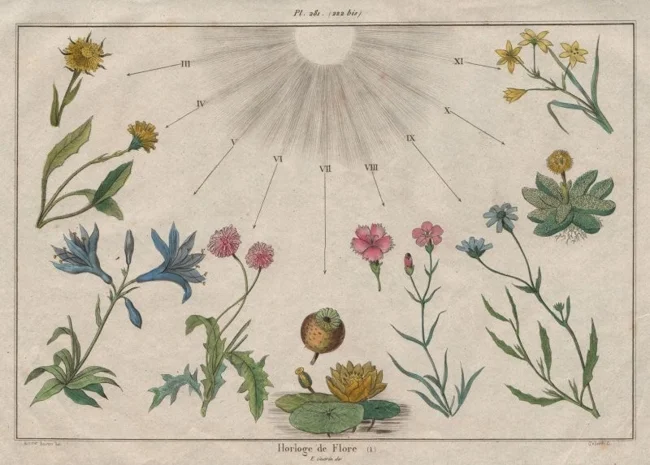

In 1748, Linnaeus wondered: if plants open and close at different times, is it possible to create a living clock out of them? It is enough to plant them in a circle in a scheduled order. And, looking at the flowerbed, you will roughly determine the time of day.

In his "Philosophy of Botany" he listed 46 such plants, 43 of which were included in his Horologium florae - a flower clock with a "dial" from 3 am to 8 pm. Among them were chicory, dandelion, marigold and even... potatoes.

Athanasius Kircher

Linnaeus entrusted his son, Karl Jr., with bringing the idea to life. He had been observing plants since childhood, and at the age of 13 he was already collecting data for the clock. But, alas, neither his notes nor the flower mechanism itself have reached us.

Predecessors and Followers

Linnaeus was not the first to try to turn plants into a chronometer. Back in 1641, Athanasius Kircher created a "sunflower clock": a flower floating in a barrel of water turned to follow the sun, and an arrow on its stem showed the time. True, they did not work for long, and critics claimed that Kircher simply hid a magnet inside.

Modern enthusiasts continue to experiment. In 2022, the Botanical Garden of Bern presented its flower clock, selecting plants ideal for the local climate.

Nature is the most inventive and virtuoso watchmaker. And if you ever need to know the time without gadgets, just look at the flowers.