Gaucho - Argentine "cowboys" who turned stabbing into art (12 photos)

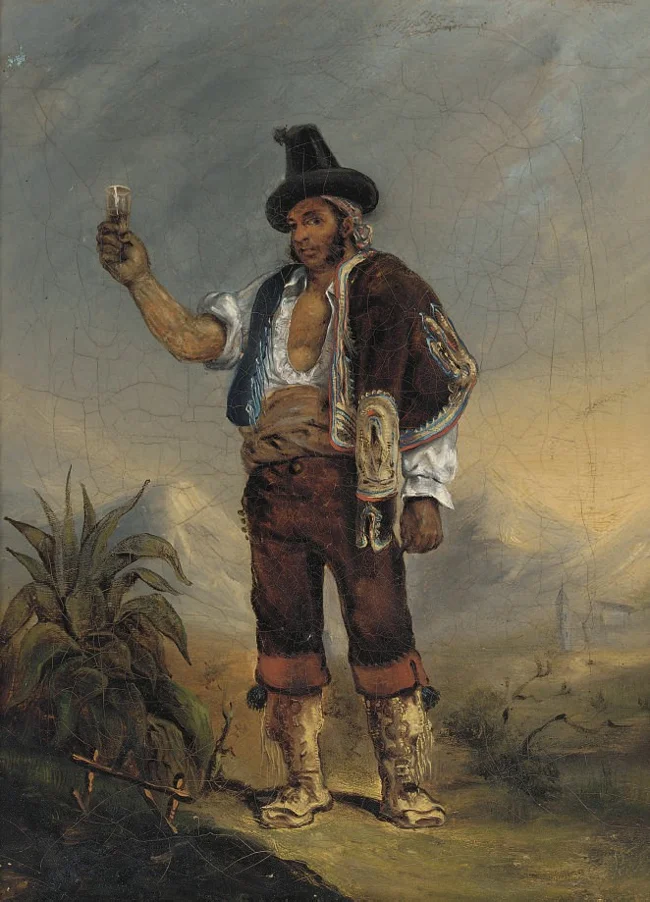

Borges called them "mestizos of white blood, led astray by the intoxication of crazy Saturdays." Charles Darwin believed that their politeness knew no bounds. However, other travelers called them nothing less than "bloodthirsty baboons." They organized truly wild entertainment on horseback and were famous for grabbing knives at the slightest provocation.

Horses, ponchos and mate - the culture of the gaucho

"Mestizos of white blood. Their enemies were mestizos of red blood. Unlike the peasants, they were not strangers to irony. They killed and died calmly. They did not die for their homeland, this is just an empty word, they died following their random leader, or if danger invited them to visit, or it just happened that way."

— Jorge Luis Borges, "Gaucho"

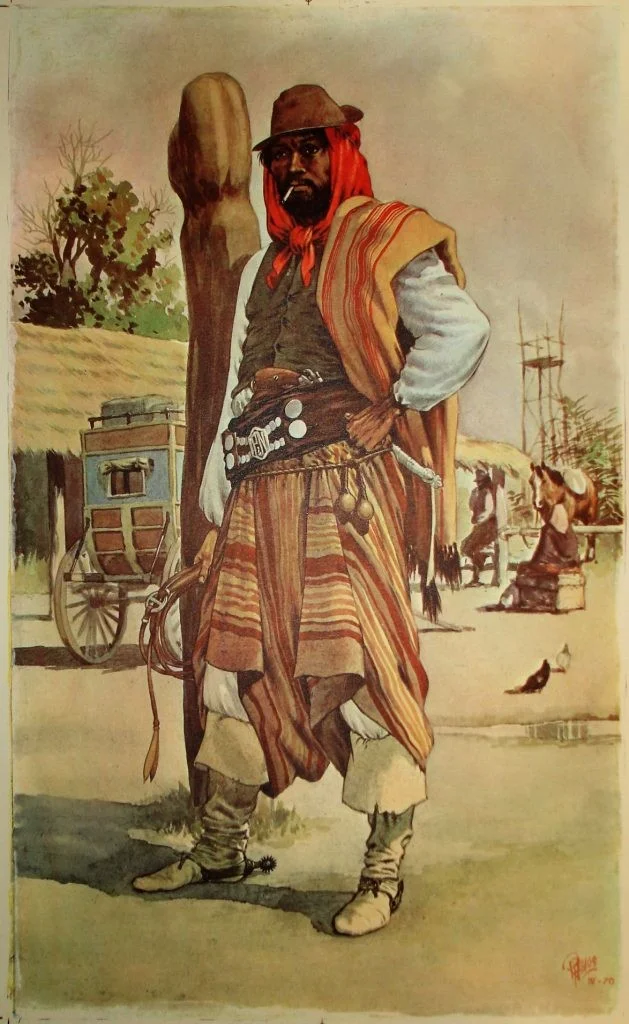

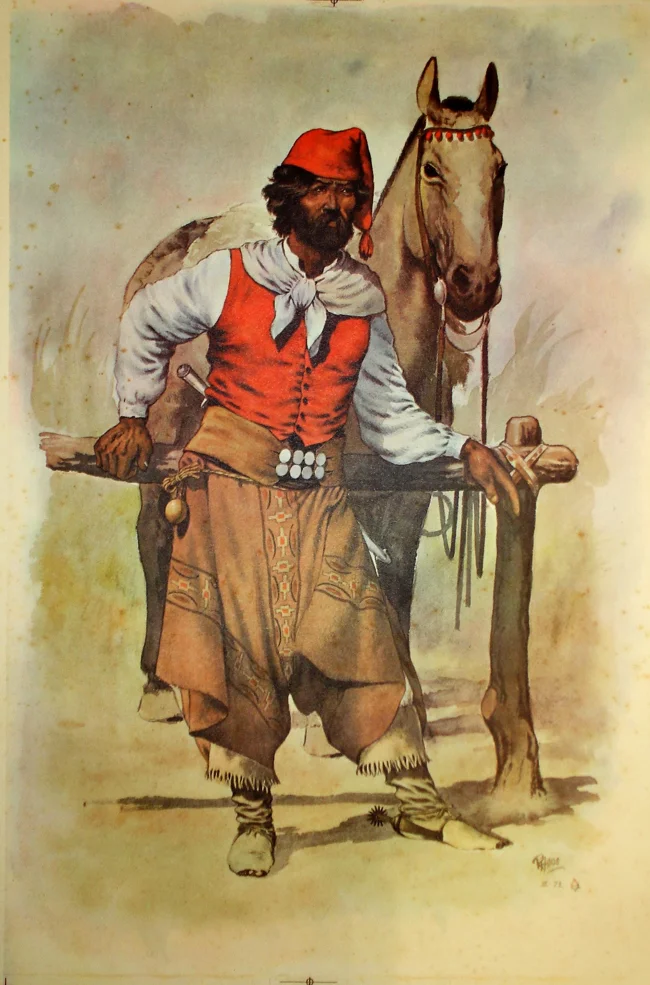

In the territory of today's Argentina, in the 18th-19th centuries, a unique situation developed when many descendants of mixed Spanish-Indian marriages were forced to survive in the pampa (steppe), hunting and herding cattle, committing robbery and fighting off the tyranny of corrupt authorities. This is how the amazing culture of the gaucho, the local equivalent of cowboys, whose name can be translated from one of the Indian languages as "vagabonds", developed.

The difficulties of survival honed the tramps' horse riding skills to perfection, because without a horse it was simply impossible to survive in the endless pampas. Local machos boasted that they could throw a hat from a horse to the ground and pick it up, hanging at full gallop and without touching the reins. Such skills are easy to imagine if you know how the gauchos trained.

In the article by researcher Richard W. Slatt, "The Death of the Gaucho and the Rise of Equestrian Sports in Argentina," a whole list of such entertainment-training is given. For example, pechando is a game where two riders crash into each other at speed, fall off their horses, get up and repeat the action again until one of them drops out due to injury or fatigue. Maroma is when a rider jumps from a special crossbar onto the back of a galloping wild horse or wild bull and stays there until the horse begins to obey him and the bull dies.

Rekado is a game like picking out a hat, only much more complicated. The rider would start unfastening parts of the saddle at full gallop and throw them on the ground, and then at the same speed would put them back together. But the toughest test was called pialar - the gaucho would fly past his friends at full gallop and they would try to throw a lasso on his horse's legs. Naturally, the unfortunate animal would fall, sometimes breaking its legs. And the rider had to survive. It sounds like a completely idiotic entertainment, but it made sense. Gauchos did not take great care of their horses, each had several. And in the steppe, there were often burrows of rodents or other animals, and the ability to survive a fall from a horse at full gallop was worth its weight in gold.

In addition to the horse, a special cape, a poncho, was always an attribute of a real gaucho. In fact, it is just a large rectangle of woolen fabric with a hole for the head. It was used as outerwear, as a table for playing cards, and as a blanket for sleeping. And sometimes it became a banner. Researcher D.L. Cherevichnik in his book "World History of Stabbing: Popular Knife Duels in the 17th-20th Centuries" writes that General Rosas's poncho flag was red, and Juan Lavaye's was the color of the sky.

Types of ponchos

The gauchos are also known for their passion for mate - a drink made from holly leaves, which were first dried and crushed, and then brewed. Due to the presence of a large amount of caffeine, this drink is very invigorating. Its popularity was so great that a special “mate language” was even created, in which the additives to the drink denoted different messages.

Cherevichnik in the above-mentioned book describes these messages as follows: bitter taste – indifference, sweet – friendship, with mint balm – discontent. If mate was served with cinnamon, then they told you that they were thinking about you, and if with orange peel – “come and find me”. Mate with coffee made it clear that the insult was forgotten, with brown sugar it spoke of kinship, and with milk – of respect. If the drink was served with a herb called monarda, then they told you: “Your sadness hurts me”.

The gauchos also loved the guitar, and the singers-payadores often staged verbal duels to the chords of their favorite instrument: one asked questions, and the other had to answer them cheerfully and on-topic. Sometimes such payadas lasted from several hours to several days, until one of the masters gave in.

Horses, mate and poncho - this image was complemented by another item, without which it is difficult to imagine a dashing gaucho - a huge knife. With it, the tramp could slash the face of anyone who touched his honor.

Charles Darwin and the "bloodthirsty baboons" - the knife culture of the gaucho

Protecting one's life and honor was a priority for the gaucho. And since firearms were used more for hunting or serious conflicts due to the high cost of cartridges, the honor of the gaucho was protected with knives. Moreover, the knives could be remade from broken sabers or made by local blacksmiths, but the gauchos especially often used ordinary household knives, brought from industrially developed Europe and decorated as expensively as possible.

They were worn in a certain way, tucked behind the belt diagonally and with the handle down. And this is due to the fact that several poor fellows cut their groin area when they fell from horses, when they proudly tucked knives behind their belts on their stomachs with the blade down. For example, the peasant Lorenzo Ponce died in 1842, pierced in the groin by his own knife, when he flew over the head of a horse at full gallop.

The famous naturalist, the father of the evolutionary theory Charles Darwin personally observed the life of the gauchos and left the following description of them: "In their bright, colorful clothes, with huge spurs jingling on their heels, with knives tucked into their belts like daggers ..., they look completely different from what one might expect, judging by the name "gaucho", that is, simply a peasant. Their politeness has no limits, they will never drink vodka if you do not try it first, but even when they make their extremely elegant bow, their appearance is such as if they would not mind cutting your throat at the first opportunity."

Other travelers were less kind in their descriptions of the gauchos. The words of one of them, unfortunately, without mentioning the author's name, are quoted by the same Cherevichnik: "The gauchos are the inhabitants of the endless plains called pampas, and outwardly look like a fine race, but compared to the peasants of England or France, they are not much better than a special subspecies of bloodthirsty baboons."

Most often, gaucho fights took place in pulperias, local taverns where people exchanged news and had a glass or two. They fought right in the courtyard of the establishment, and on the doors of many of them there were several dozen crosses, for the number of people killed there.

Usually the challenge to a duel was verbal, but sometimes a poncho was used for it. For this, the challenger dragged one end of the cape along the ground and the person who stepped on the edge of the poncho accepted the challenge. Moreover, the masters often performed such a feint: beginners tried to step on the edge harder and then the gaucho pulled the cape with a sharp jerk, and the opponent lost his balance, falling to the ground.

During a duel, the gauchos also used a cape, wrapping it around their unarmed hand, defending themselves from the opponent's knife. According to Cherevichnik, there is a poncho known to have eighty cuts on it, and one of the craftsmen, Fernando Luna, fought off two knife-wielding troublemakers with a rolled-up poncho until the police arrived and arrested them.

Despite their reputation as "bloodthirsty baboons," the gauchos tried not to kill their opponents in a duel, but only to leave them with a humiliating cut on their faces. But if they were seriously attacked, wanting to take their lives, they fought back desperately. Cherevichnik tells the story of a gaucho named Jack, who killed a guy in a duel who had a bunch of relatives who wanted revenge. At night, nine people came to the ranch where our hero was sleeping. Leaving two to guard, the seven of them ran into the room with the intention of stabbing Jack. But it was not to be. Jumping up abruptly and using his agility and knowledge of the arrangement of furniture in the dark room, the gaucho killed three and cut up four so badly that they ran away and swore off dealing with him forever.

Such skill is not surprising, because future gauchos began training from childhood. They trained with sticks, the tips of which were smeared with soot to indicate the place of the injection, and sometimes they took real knives in their hands. Such play fights were called "visteo". Sometimes they led to tragedies. For example, in one of these training fights, the boys got so carried away that when one of them fell, the second immediately jumped up to the lying one and stabbed him with a knife.

And a gentleman named William Morley describes a truly horrific situation: "Even small children were perfected in this terrible skill - in one large family where I spent a lot of time, two little girls got together to fight with long knives. Suddenly, the younger of them stabbed her opponent in the right eye, which resulted in his blindness."

How the Gauchos Moved to the City and Invented the Tango

Gradually, the authorities began to tighten the screws more and more, punishing for carrying and using knives, and then the usual way of life of a shepherd or a hunter of large game ceased to bring in income. Gauchos flocked to the cities, especially to the capital of Argentina, Buenos Aires.

They were engaged in driving cattle from the pampas to the city slaughterhouses and became heroes of the poor neighborhoods, receiving the nickname "compres" - "kumanki". The city youth, having seen the brave gauchos with knives, began to copy their behavior and they were nicknamed "compadritos". It was this youth subculture, according to one version, that was involved in the emergence of the famous tango. In the newspaper "Critica" on September 22, 1913, an article was published under the title "Viejo Tanguero", which said that compadritos, visiting parties for the dark-skinned population of the capital, saw elements of a dance called "tango" there. Returning to their poor neighborhoods, they began to use its movements in their dance "milonga", practicing it in local brothels. Much later, the tango we are accustomed to emerged from this hot cocktail. Whether it was true or not is forever hidden in the fog of history, but if you travel around Argentina, try not to step on a carelessly lying poncho. What if its owner is an heir to the blood of fierce gauchos, and your face is dear to you as a memory.