Group intelligence of ants versus humans (2 photos + 1 video)

Recently, you may have seen ants solving a puzzle together. Here's how humans do it.

Ants are some of the most social creatures on Earth. When observing them, you'll rarely see one of their kind alone: they almost always work together. Humans are also known to be social creatures, although some of us value solitude. Both ants and humans have the unique ability to collectively carry loads that are much larger than themselves. This property was the basis for an unusual study conducted by Professor Ofer Feinerman from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

The scientists compared the ability of humans and ants to cope with the task of moving a large object through a complex maze. The results of the work shed light on the features of group decision-making, as well as the pros and cons of collective and individual strategies.

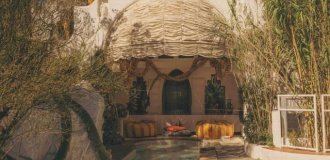

For the experiment, the team of scientists developed a version of the so-called “piano-moving task” - a classic task from the field of robotics and motor planning. Instead of a piano, the participants of the experiment were given a large T-shaped object that had to be moved through a “maze” - three rooms connected by narrow passages.

The ants chosen for the experiment belonged to the species Paratrechina longicornis (or "crazy ants") - because of their tendency to move chaotically. People were divided into three groups: single players, small teams (6-9 people) and large groups (up to 26 participants). The ants worked in a similar way: alone, in small groups (about seven individuals) and in large groups (up to 80).

To make the comparison fair, people were limited in their communication abilities. They were forbidden to talk and gesture, and sometimes even asked to wear masks and sunglasses to hide their facial expressions. In addition, they were allowed to hold the load only by special handles imitating the grips of ants.

Unsurprisingly, in individual tests, people significantly outperformed the ants. Thanks to their strategic thinking and ability to plan, they easily coped with the task. However, in group tests, the results were unexpected: large groups of ants often outperformed people. The ants demonstrated collective memory, which helped them avoid repeated mistakes, and acted more harmoniously.

While people in groups showed reduced productivity due to limited communication, ants, on the contrary, were more effective. They were not distracted by short-term “attractive” solutions, choosing the path that turned out to be most profitable in the long term.

According to Professor Feinerman, the success of ants is explained by the peculiarities of their social structure. The ants in a colony are sisters, have common interests, and are completely focused on cooperation. This is why colonies are sometimes called “superorganisms” — a kind of living body made up of many interconnected “cells.”

“Our results show that for ants, collective action leads to an increase in overall ‘brain power.’ However, in the case of humans, we did not see such an effect. The so-called ‘wisdom of crowds’, popular in the age of social media, did not manifest itself in our experiments,” Feinerman concluded.