Incompatibility of innovation and reality. The tragedy of HMS Captain (5 photos)

Innovations in the navy often encounter resistance from old, honored sailors. However, this is typical for all military forces. And indeed, old does not mean bad. In addition, it is far from certain that the innovation will be good, and it is even more unknown how much effort, money, and even blood will be needed for it to be accepted and used in the navy.

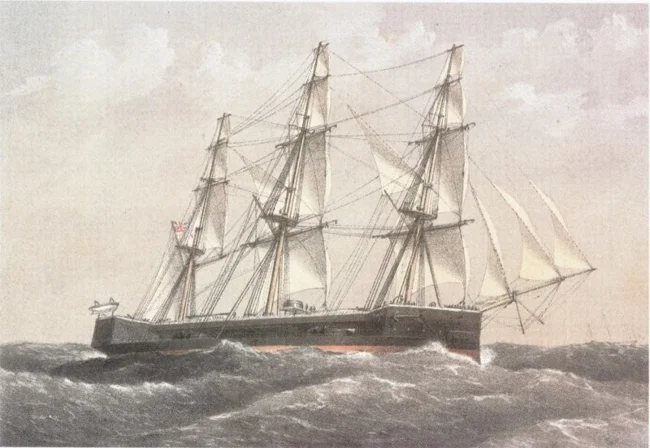

HMS Captain

The middle of the 19th century was exactly such a time. Scientific and technological progress did not stand still. The steam engine gradually replaced the sail, and wooden ships gave way to steel vessels. Of course, the innovations introduced at sea were often unreliable and caused rejection by decision-makers and people in power. Nevertheless, it was impossible to remain on the sidelines of technical progress. This was especially true for Great Britain, the then "mistress of the seas", which constantly needed not only quantitative but also qualitative superiority of its fleet over competitors. Unfortunately, it was very often possible to identify the shortcomings of innovations in those days only in practice. And such identifications were regularly paid for with lives and blood.

HMS Captain was an ironclad of the British Navy, commissioned in 1870. Today, this ship might seem a little strange. She had a steel armored hull, but at the same time a full sail rig. However, we must not forget that those years were a time of mass innovations in the navy. The design of the battleship was in many ways innovative and contrary to the then existing opinions about the appearance of a warship.

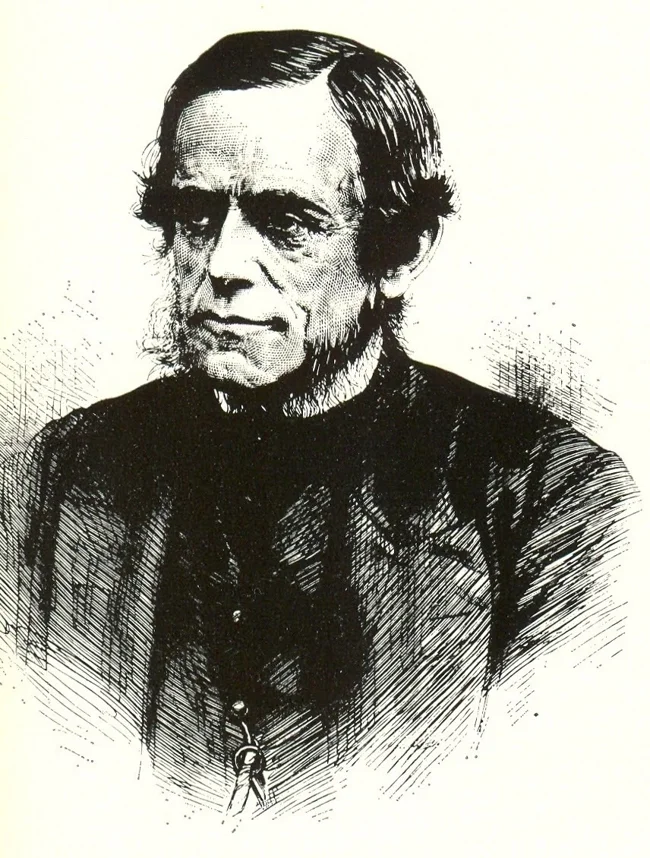

The ship carried four "25-ton" (305 mm) and two "6.5-ton" (178 mm) guns. The main feature of the battleship was that for the first time the main caliber guns were located in rotating turrets. The ship's design was the brainchild of engineer and designer Cowper Phipps Coles, an authoritative naval designer, and also an extremely well-known person in England at that time. It was his authority and popularity that allowed him to lobby for the construction of a new battleship, although the design contained many innovations that the Admiralty opposed to the last.

The main idea of Coles was to ensure maximum firing angles for all the turrets of his new ship. However, given the need to place masts, this presented a problem. And then Coles resorted to a radical solution. An additional deck, called the "hurricane deck", was built above the towers. The masts were mounted on it. In addition, to achieve maximum gun aiming angles, HMS Captain received fairly low sides.

This design was justified. Thanks to it, the ship had the ability to fire from almost any angle, unlike most of its contemporaries. Combined sail and steam armament provided it with maneuverability in battle. According to modern historians and experts, at the time of commissioning, the battleship had perhaps the most powerful artillery armament in the world.

Nevertheless, the new ship also had opponents. The experts at Lairds calculated that the battleship could withstand a list of only 21 degrees, and at 14 degrees the water reached the edge of the deck. At the same time, HMS Captain was far from the largest ship in the British fleet. The battleships of the Northumberland and Minotaur types were larger and more massive. But the prospective battleship surpassed them in speed and maneuverability due to its narrower and more streamlined hull. In addition, the outdated arrangement of guns on these ships, the same as on wooden ones, made them vulnerable to Coles's battleship, which was capable of firing from any angle.

Cooper Phipps Coles, 1819-1870. Inventor and shipbuilder of the era of the first ironclads

When HMS Captain was launched, another incident occurred that was perceived by many as a bad sign. When the flag was raised over the ship, it was discovered that for some reason it was upside down. The acceptance committee also found that HMS Captain was overloaded by more than 700 tons from the original design. There were even opinions that it would not be accepted into service at all due to glaring shortcomings. But Coles' authority was higher. On April 30, 1870, the battleship entered service. At that time, it was considered "the best ship in the fleet."

At first, everything went well. HMS Captain passed sea trials, demonstrating high speed and maneuverability. After testing the guns, the ship even got into a storm, but weathered the storm without any problems. Even on a big wave, HMS Captain reached a speed of 14.2 knots, becoming one of the fastest battleships of its time. Coles, in order to finally dispel all doubts, insisted on his personal presence on the third voyage to check the operability of the mechanisms of his brainchild.

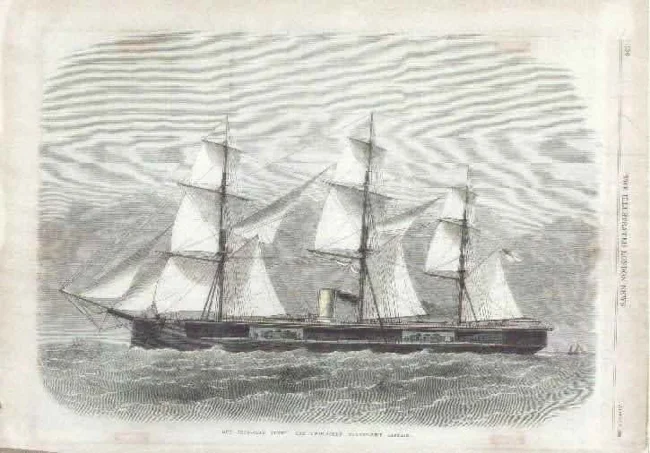

HMS Captain, illustration in the book "Our Ironclad Fleet", August 1869

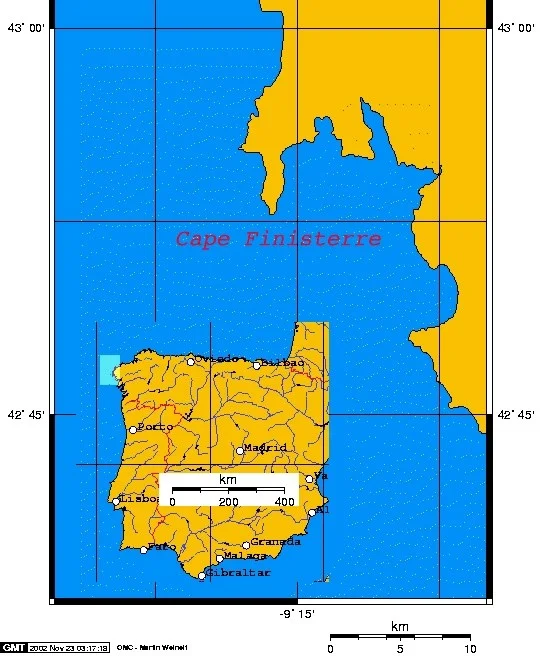

On August 4, 1870, the squadron, which included HMS Captain, called at Gibraltar, and on August 31 - at Vigo. On September 6, the unit was en route to England, about 20 miles from Cape Finisterre. The sea was rough. Admiral Milne, who commanded the squadron, paid a visit to the ironclad for the purpose of inspecting it. He immediately noted that the ship was listing heavily and considered it dangerous. Coles said that this was provided for by the design and there was no reason to worry. However, the admiral, despite the invitation, refused to spend the night on the new battleship.

On the night of September 6-7, the weather deteriorated sharply. A squall hit. According to observers, the waves reached a height of 8 meters. Admiral Milne, who was on another ship of the squadron, later wrote:

… "At this moment, the Captain, under steam, was behind the flagship and seemed to be approaching her ... at 01:15, the ship was on the leeward shell of the Lord Warden, approximately 6 R behind her beam; the topsails were partly reefed tightly, partly furled; the foresail was reefed, the mainsail was furled already at 17:30, I did not see any fore-and-aft sails. The ship was listing heavily to starboard, with the wind from the left. Her red light was clearly visible at this time. A few minutes later I looked in her direction again, but it was raining heavily, and the light was no longer visible. The squall with rain was very strong... At 02:15 (7th) the wind died down a little, changed its direction to NW and blew without squalls; a heavy bank of clouds went towards the east, and clear and brilliant stars became visible; the moon, which gave quite a lot of light, was setting, but not a single large ship was visible where the "Captain" was last seen ...

British historian Wilson, being a contemporary of the death of HMS Captain, studied the events of that night in detail and described them, relying on the stories of survivors. Here is what he writes:

... "During the roll call the ship listed heavily, but righted herself again. When the men came up they heard Captain Burgoyne give the order to “let go the topsail halyards” and then “let go the fore and main topsail sheets.” Before the men could reach the sheets the ship heeled over again, even more. The angles of heel were shouted out in quick succession in answer to Captain Burgoyne’s question: “18°! 23°! 28°!” The list to starboard was so great that several men standing on the sheets were washed away. The ship was lying quite on her side at this time, slowly turning over and shuddering from every blow dealt to her by the short, white-crested waves that were running up her side.” …

The battleship turned over and sank very quickly. Only one man escaped from the interior. It was the gunner James May, who managed to escape through the gun port of the turret when the ship had already rolled over. The rest of the survivors were from the night watch on deck. HMS Captain sank at 42°36.9' N, 09°23.4' W. None of the other ships of the squadron suffered any serious damage from the night storm.

Only 18 people were saved from the ship, having managed to cling to the wreckage and an overturned boat that floated to the surface. According to them, the commander of the battleship was also in the water. But despite their cries, he did not try to save himself and quickly disappeared from sight in the night stormy sea. The ship's chief designer, Coles, also perished with the ship. Several officers, offspring of high-ranking Admiralty officials appointed to the "best ship in the fleet", also drowned with the battleship. In total, 483 people died on HMS Captain (according to other sources, more than 500), which exceeds the number of British casualties in the famous Battle of Trafalgar. To this day, this disaster remains one of the largest losses in the British Navy in peacetime from non-combat causes.

Cape Finisterre. HMS Captain sank 20 miles to the west of it

Three weeks after the incident, a trial took place. The tragedy generated a great deal of public outcry in society and the navy. Everyone wanted to know the results of the investigation, from the average citizen to the Lords of the Admiralty. After a thorough questioning of the survivors and those who participated in the construction of the ship, the court delivered its verdict:

… The Captain capsized… under the pressure of her sails, added to the pressure of the sea, and the amount of sail set on her at the time of the loss… was insufficient to endanger a ship provided with a proper margin of stability.

The court… held that the Captain had been built in concession to public opinion, expressed in Parliament and elsewhere, and in opposition to the opinion and views of the Comptroller of the Fleet and his department, and that all the evidence showed that they were generally against her construction.

It then appeared that the Captain had been accepted from the builders with a considerable deviation from the original design, with a draught exceeding two feet… and with a dangerously diminished stability”…

But the one who could be directly blamed for what had happened was already at the bottom. Coles perished with his brainchild. According to historians, the person who suffered most from the incident was First Lord of the Admiralty Hugh Childers, whose relative also died on board HMS Captain. Having given in to public pressure and allowing the ship to be built, Childers effectively became responsible for its death. He tried to shift the blame to anyone, blaming the late Coles, the Controller of the Fleet, who gave the final permission for the construction, and the Lairds company. However, due to the great public outcry, the First Lord of the Admiralty and the Controller of the Fleet eventually resigned. According to historians:

… "the disaster was almost predicted by the Admiralty itself, and the British public and the press were to blame for it, constantly insisting on the construction of a ship of an obviously unsuccessful type" …

As a result of the investigation, no one was punished. However, after this tragedy, shipbuilders around the world abandoned the construction of low-sided battleships with full sail rigging, where the seaworthiness and stability of the ship were sacrificed for combat capabilities. HMS Captain itself remained in the history of the fleet as an innovative ship that could not withstand a collision with reality.