A grand scandal and almost brilliant scam with Portuguese banknotes from 1925 (6 photos)

Throughout history, there have been people who have sought to deceive others by producing counterfeit versions of valuable goods. Perhaps one of the most harmful of these is counterfeit money.

Counterfeit currency undermines the foundations of trust and stability that underlie a healthy economy by causing people to doubt the authenticity of the currency they hold, causing inflation and loss of purchasing power, as well as a loss of confidence in the country's financial institution in the global economy.

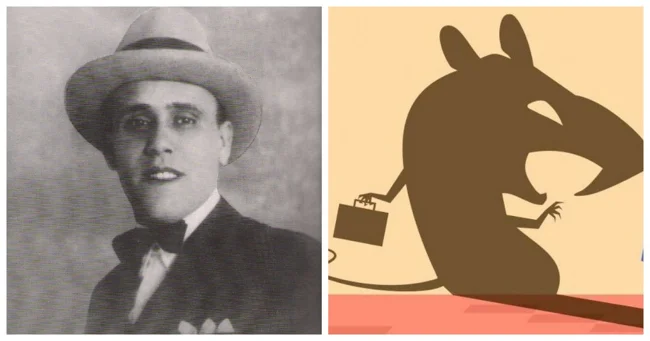

Alves dos Reis

One of the most notorious counterfeiters of the 20th century was Portuguese criminal Alves dos Reis, who nearly destroyed the Portuguese economy by exploiting loopholes and inefficient practices in his country's financial system. Unlike other criminals, Alves' genius was that he did not counterfeit Portuguese currency himself. Instead, his network managed to trick a British banknote printing company into believing they were working on behalf of the Portuguese government. And thus trick them into printing money for him.

Reis came up with his ingenious scheme while in prison, serving time for embezzlement. At the time, Germany was experiencing one of the worst inflations in history, and the flood of government banknotes prompted Reis to study the workings of Portugal's banknote-issuing institution, the Banco de Portugal. He learned that Portugal had not been on the gold standard since 1891, allowing the bank to issue banknotes that greatly exceeded its authorized capital. Reis also learned that the Banco de Portugal sometimes printed banknotes secretly, without recording the transactions in its books or informing the government of the increase in the number of banknotes in circulation. Reis also discovered that the Banco de Portugal had no mechanism to prevent the issuance of duplicate banknotes. Reis calculated that he could inject 300 million escudos (the equivalent of one million British pounds at the 1925 rate) into the Portuguese economy without disrupting the country's central banking mechanism.

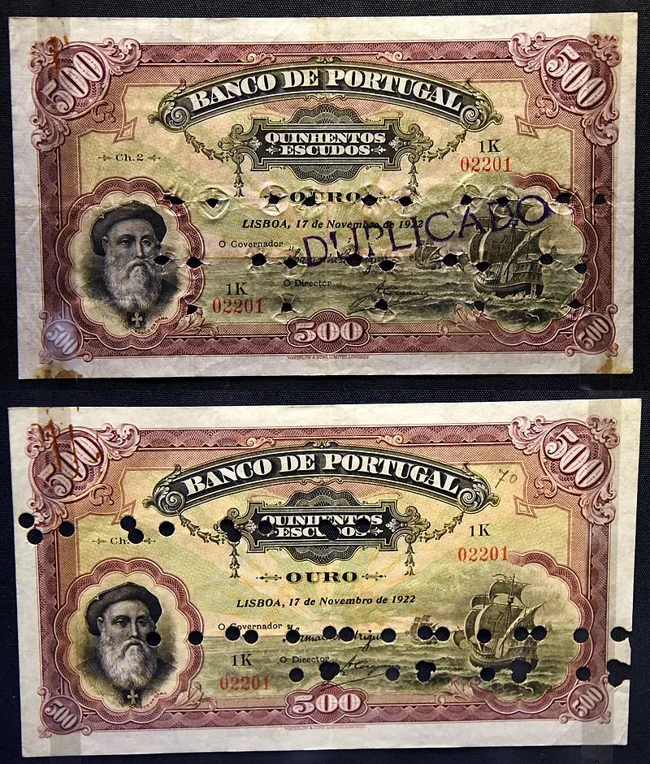

A counterfeit 500 escudo note (top) and a genuine note (bottom) from the Bank of Portugal. Both have the same serial number 1K 02201, 1922. On display at the British Museum in London.

Once released from prison in August 1924, Reis quickly set about implementing his plan.

He first gained the trust of another small-time con man, José Bandeira, whose older brother was the Portuguese minister in The Hague. Through José he made contact with two more accomplices: Karel Marang, a Dutch merchant, and Adolf Hennis, a German merchant. Both Marang and Hennis had shady backgrounds and were not averse to engaging in such dubious enterprises.

Reisch sent Karel Marang to London to meet Sir William Waterlow, managing director of Waterlow and Sons Limited, the British printers that printed Portuguese currency for the Bank of Portugal. Marang introduced himself as an authorized agent of the Bank of Portugal with a mandate to negotiate a major financing operation in the economically weak Portuguese African colony of Angola. He explained that for political reasons the contract required the utmost confidentiality and that he was to be the sole intermediary between the printer and the Bank. Sir Waterlow, quite naturally, insisted on having a letter of authorization from the Governor of the Bank of Portugal. However, he made the mistake of not contacting the bank directly, but asking the conspirators to provide documents. Marang happily agreed and produced false documents.

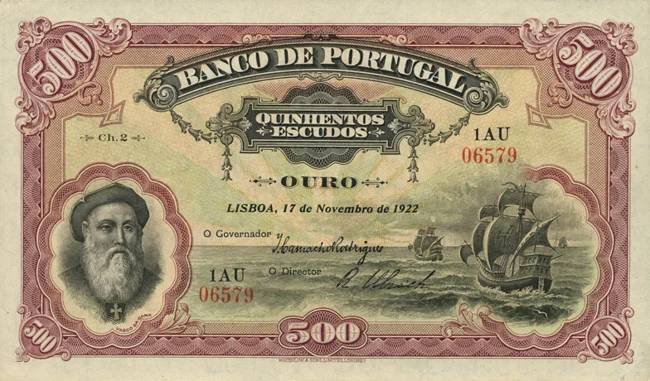

One of the counterfeit notes

Although Marang emphasized the secrecy of the entire transaction, Sir Waterlow informed his representative in Lisbon, Henry Romer. When Romer learned of the unusual transaction, he sent Sir Waterlow repeated warnings about the illegality of the matter, emphasizing that only the National Bank had the right to issue banknotes in Angola. But Sir Waterlow turned a deaf ear.

In early 1925, Waterlow and Sons Limited printed 200,000 Portuguese 500 escudo notes with Vasco da Gama's image, for a total of 100 million escudos, and delivered them to Reis.

The next step was to put these notes into circulation. Reis hired people to open bank accounts in suburban and suburban branches of large banks with Vasco da Gama notes and then withdraw the money in genuine notes from the head office of these banks.

Crowds of people rush to the Bank of Portugal building in Lisbon to exchange counterfeit notes (December 8, 1925)

With the laundered money, Reis and his fellow swindlers began investing huge sums in real estate and business, creating a temporary boom in the Portuguese economy. Reis bought the Palace of the Golden Boy (Palácio do Menino de Ouro, now the British Council building in Lisbon), three farms, a taxi fleet, and spent a huge amount of money on jewellery and expensive clothes for his wife. José Bandeira bought retail stores and invested in all sorts of businesses; he tried to buy the newspaper Diário de Notícias, but without success. Reis also opened a new bank.

The final stage of Reis's plan was to gain control of the Bank of Portugal, which would allow him to hush up the whole affair. To do this, he began buying up shares in the Bank of Portugal, intending to gain a controlling interest. By the end of 1925, Reis had acquired 10,000 of the 45,000 shares needed to gain a controlling interest.

The unique success of Reis's new bank and his own growing wealth attracted the attention of the Portuguese newspaper O Sêculo, which raised questions about how this particular new bank was thriving and how it was possible that it was lending at low interest rates.

On December 4, 1925, a cashier at a money changer in Porto, who was himself involved in laundering money for Reis, became suspicious and took one of the notes to the local manager of the Bank of Portugal, suspecting that the notes might be counterfeit. The bank's employees examined the notes but could find no difference from the real thing. After a tedious and fruitless investigation, they finally noticed that the notes had duplicate serial numbers, and Reis's scheme collapsed.

He was arrested, convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison. He was released after serving fifteen years and died of a heart attack in 1955.

Bandeira received a 15-year sentence, served it, and after his release went into business - a chain of nightclubs. He died in 1960 in Lisbon, a respected man of modest means.

Maranga was tried in the Netherlands and sentenced to 11 months. But since he had already served that time in prison awaiting trial, he was immediately released. He later acquired a small electrical engineering company in France, eventually becoming a respected industrialist, family man, and French citizen.

Hennis fled to Germany, where he lost most of his fortune in bad investments. He died in poverty in 1936.

The Bank of Portugal sued Waterlow & Sons for negligence and won.

The House of Lords ruled that Waterlow must pay the bank £610,392 in damages and a further £95,000 to cover the costs of the hearing. The firm never recovered from the financial losses.

The Reis fraud had huge repercussions for Portugal's economy and politics. It caused the Portuguese escudo to fall in value and public confidence in the country's financial institutions to be lost.

Although the Bank of Portugal has withdrawn all 500 escudo notes from circulation, many are still in private hands. They can fetch serious money at auction. One was sold in 2016 for $7,500.