The ghost town of Nan Madol: how technology is changing our understanding of history (8 photos)

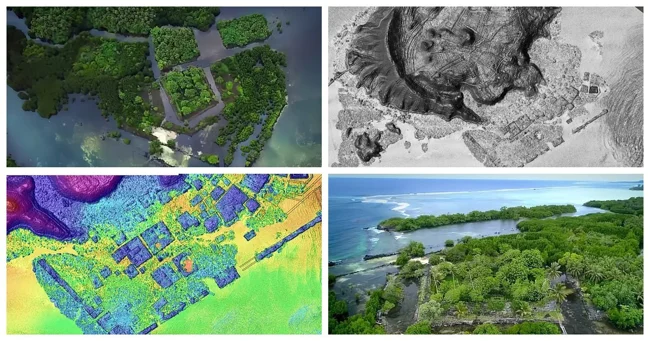

Recent laser surveys on Temwen Island have revealed the remains of the lost city of Nan Madol, known as the “Venice of the Pacific,” challenging traditional notions of Micronesian agriculture and culture. Researchers are seeking to preserve Nan Madol as a UNESCO World Heritage Site to protect its unique historical heritage.

Recent high-precision laser surveys carried out by aircraft over the small Pacific island of Temwen have revealed just how sophisticated its lost city of Nan Madol once was. Known as the “Venice of the Pacific,” this megalithic stone city was reminiscent of the mythical Atlantis. Its discovery in 1928 inspired H. P. Lovecraft to write his famous book, The Call of Cthulhu. Dozens of researchers are now racing to uncover the full extent of the Nan Madol ruins, with plans to preserve the city as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

An aerial survey using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) laser mapping technology has revealed a complex and extensive landscape of agricultural sites hidden beneath the vegetation of Temwen Island. The discovery could change the way we think about many Pacific Island cultures, showing that societies thought to have relied on fishing and natural resources actually practiced sophisticated agriculture.

An international team of researchers has noted that LiDAR can reveal entire archaeological landscapes hidden beneath dense vegetation, making it comparable to radiocarbon dating as a major advance in archaeology. At Nan Madol, as well as in the dense rainforest where more ruins are hidden, scientists led by the Baltimore-based Foundation for Cultural Site Research and Management (CSRM) were able to map a network of irrigation terraces that once provided the stone city with fresh water.

National Geographic explorer Albert Lin's documentary series called the ruins of Nan Madol (aerial view) a "Pacific ghost town" in a 2019 episode

Archaeologists have long believed that Nan Madol was active from 1100 to 1628 CE, and fell into decline after the fall of the local Saudeleur monarchs in the 17th century. Considering that Temwen Island is just over 2.5 square kilometers in area, hundreds of times smaller than many Hawaiian islands such as Oahu (1,545 square kilometers), the researchers were amazed by the level of sophisticated landscape engineering.

Douglas Comer, project leader and author of Mapping Archaeological Landscapes from Space, noted: “There is a general consensus among archaeologists that Micronesia did not experience agricultural intensification through formal field systems.”

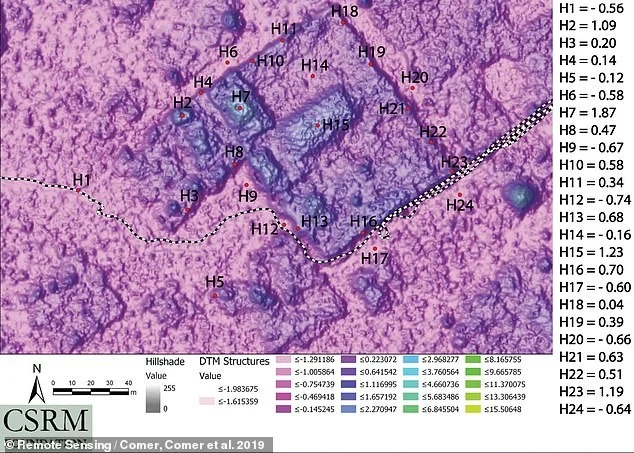

A "Colorized Multi-directional Hillshade LiDAR Digital Terrain Model" that helped researchers delineate islands and long-vanished man-made waterways at the site

Collaborating with the local College of Micronesia, as well as Stanford, Sandia National Laboratory, and others, Dr. Comer's team has in recent years challenged long-held beliefs that the culture relied heavily on fermented "breadfruit" (Artocarpus altilis).

The “remarkably complex system of irrigated fields covering Temwen Island,” the scientist noted, suggests early and sophisticated agriculture using taro root, which would have provided greater food security and economic power. In a 2019 paper published in the journal Remote Sensing, he noted that Temwen’s system also shares similarities with several Polynesian terracing systems, including the Kohala field system in Hawaii and the recently described slope terraces at Tutuila in American Samoa.

To protect and preserve Nan Madol for future generations, last year the team worked with the U.S. Forest Service and Arbor Global to train locals to prevent wild vegetation from destroying the city’s stone structures. The Nan Madol defenders were trained to “use and maintain chainsaws, climb trees, trim branches, fell trees, and plant suitable vegetation,” the U.S. Forest Service said.

These skills will be critical to restoring the island’s ecosystem in harmony with the historic ruins, especially replacing the island’s many wild mangroves, which grow quickly — up to 1.5 meters per year — in part because they reproduce not by seeds but by “mini-trees” that literally sprout from the ground. “Vegetation not only hides the wonders of the site, it also destroys it,” the CSRM Foundation team noted in 2021.

The researchers had to use more than half a dozen software packages to interpret the LiDAR scans, or “digital terrain model” (DTM). This model, sometimes referred to as a ‘bare ground model’, displays LiDAR scans taken on the ground, as opposed to those reflected off the forest canopy.

‘Bare Ground Model’

The colourful, multi-directional LiDAR terrain model helped Dr Comer and his team discover hidden islands and long-forgotten man-made waterways on the site. The tool was particularly important in revealing the complex patterns of flats, berms and water channels on Temwen Island, many of which are subtle, obscure features that would not have been visible without these analysis tools.

But it wasn't just aerial lasers and computer programs that confirmed the appearance of these so-called "berms" — the raised banks that surround rivers and canals. "Field observations confirmed that the earthen berms between low areas act as retaining walls for water," Dr. Comer and his colleagues note, "altering the natural flow patterns that would be expected based on the topography of the area."